Made in America: The Next Boom

JANUARY 2013

After decades of outsourcing, however, the U.S. is quietly enjoying a manufacturing revival, and companies like Apple (ticker: AAPL), Caterpillar (CAT), Ford Motor (F),General Electric (GE), and Whirlpool (WHR) are making more of their goods on American soil again. It isn’t just U.S. companies that are drawn to our cheap energy, weak dollar, and stagnant wages. Samsung Electronics (005930.Korea) plans a $4 billion semiconductor plant in Texas, Airbus SAS is building a factory in Alabama, and Toyota (TM) wants to export minivans made in Indiana to Asia.

The Rust Belt owes its new shine to many factors, including rising wages and industrial-land costs in Asia. But none is bigger than the U.S. energy boom. Thanks to a head start in extracting oil and gas from shales, North America now produces far more natural gas than any other continent. Unlike oil, gas isn’t easily transported across oceans, and a result is some of the world’s cheapest energy within our reach: Natural gas here costs $3.55 per million British thermal units, versus roughly $12 in Europe and $16 in Japan. Cheap energy not only reduces our trade deficit and our addiction to Middle East oil, it also makes our factories more competitive globally — a boon for a country that had gone from exporting American goods to exporting American jobs.

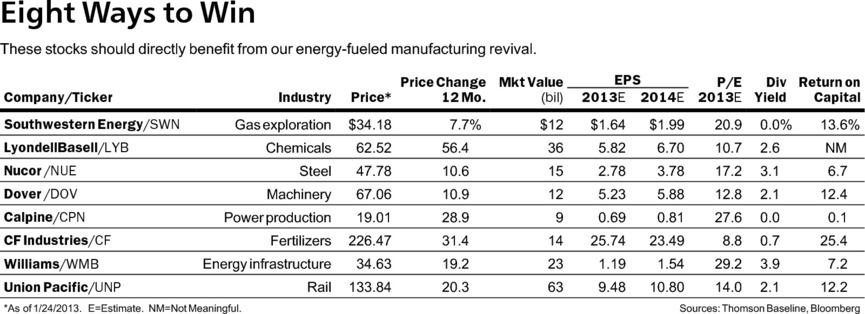

The biggest beneficiaries are energy-guzzling companies like chemical producers and steelmakers, and Barron’s has identified eight stocks that should prosper in our gas-fueled manufacturing upswing. They are Southwestern Energy, LyondellBasell Industries, Nucor, Dover, Calpine, CF Industries, Williams, and Union Pacific. But any glow will also rub off on regional lenders, home builders, and local small businesses. “The U.S. is the Saudi Arabia of natural gas,” declares Nancy Lazar, co-head of the New York research firm International Strategy & Investment. “And Middle America is my favorite emerging market.”

Our energy boom got cracking with fracking, a controversial process in which pressurized fluids are pumped through rock formations, often a mile or more under the ground, to extract oil and gas. Critics condemn fracking, which they contend causes environmental harm, but even they agree that it’s led to an abundance of cheap gas. Over the past six years, U.S. production of petroleum and natural gas has jumped from 15 million barrels of oil-equivalent a day to 20.1 million, a 20-year high. Over the same period, imports have fallen from 14 million barrels a day to below eight million, a 25-year low.

It’s a sign of the times: Graduates from the South Dakota School of Mines & Technology — acceptance rate: 88%; mascot: Grubby the Miner — now command a median starting salary 16% higher than that of Yalies.

By 2020, the U.S. will become the world’s biggest oil producer, says the International Energy Agency. By 2025, North America will be a net energy exporter, predicts ExxonMobil (XOM).

That edge should remain ours for decades. “It isn’t just the huge reserves we have underground,” says Tim Parker, who manages T. Rowe Price’s natural-resource stock portfolios. “No one else has our predictable cocktail of infrastructure already in place, know-how, a relative abundance of water, and a favorable royalty regime that give landowners a stake in the exploration game.” Europe, for instance, is averse to fracking and has little infrastructure; Japan has hardly any shales; and while China has vast reserves, only shales nudging the Yangtze River have enough water for fracking.

Of course, an especially frigid winter could send gas prices soaring, but any such spike should be temporary. Given our expanding reserves and record inventory, commodity strategists expect U.S. natural gas to stay between $3 and $5 per million BTUs for years — well below prices abroad.

CHEAP GAS ISN’T THE ONLY booster in our tank. In the decade since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, that nation has become Earth’s low-cost factory. But wages and benefits there are rising 15% to 20% a year, while they’re stagnant here. Despite Beijing’s efforts to hold it down, the yuan has gained 33% against the dollar since 2005. Industrial land averages $10.22 a square foot across China, but rises to $11.15 in the coastal city of Ningbo and $21 in Shenzhen — compared with $1.30 to $4.65 in Tennessee and North Carolina. “Within five years, the total cost of producing many products will be only about 10% to 15% less in Chinese coastal cities than in parts of the U.S. where factories are likely to be built,” says Hal Sirkin, a senior partner at Boston Consulting Group. Add duties and shipping, and the cost gap shrinks further.

Location-scouting manufacturers also are looking beyond mere costs. Moving part of their supply chains closer to the U.S. — still the world’s biggest consumer market — helps companies react faster to changes and also speeds innovation, says Gary Pisano, a Harvard Business School professor. Adds Robert McCutcheon, who heads PricewaterhouseCoopers’ U.S. industrials practice: “You protect not just the intellectual property of your products, but your processes as well.”

Companies, of course, won’t completely shutter overseas factories. U.S. corporate taxes are still high, compared with many other countries’, and there’s a limit to how many jobs will return, given advances in automation and productivity. But BCG’s Sirkin conservatively estimates that 2.5 million to five million manufacturing positions will be added by 2020, which could shave two to three percentage points from our unemployment rate, now near 7.8%. We’ll also expand exports, at the expense of higher-cost developed rivals, such as Germany and Japan. And U.S. ports stand ready and idle, operating at just 54% of capacity, well below 59% in Europe, 67% in Latin America, and 76% in Southeast Asia.

Busier factories would help the entire country. For every dollar spent on manufacturing, another $1.48 is added to the economy, says the National Association of Manufacturers. Another bonus: Manufacturers account for two-thirds of what the private sector spends on research and development.

And we’ve only just begun: Abundant gas and a weak dollar are long-term trends, and U.S. wages should behave until unemployment falls well below 6%, says Jeffrey Korzenik, chief investment strategist at Fifth Third Private Bank. “Offshoring had gone on for decades, but the re-shoring trend is only in year two or three.”

Here are eight stocks that should benefit:

Southwestern Energy (SWN)

Cheap energy is a boon for manufacturers, but a curse for exploration companies, and investors are shunning the producers most exposed to slumping gas prices. With 99% of Southwestern’s production and reserves in natural gas, you’d think the Houston company’s managers would be anxiously sweating over prices near decade lows.

But they aren’t. That’s because Southwestern is a highly efficient, low-cost producer. It works its 926,000 acres in the Fayetteville shale with operational aplomb, using dense wells, some of its own rigs, and vertically integrated services. The company has another 187,000 acres in the Marcellus shale. At $34, its shares trade at a small premium to its gassy peers but still a discount to its net asset value.

Ken Settles, who co-manages the RS Global Natural Resources Fund, expects gas prices to hit $5 to $6 eventually. “But the benefit of focusing on a low-cost producer is that, even with gas prices below sustainable long-term levels, Southwestern’s assets are still profitable and creating value for its owners.”

Southwestern plans to increase 2013 production by 11% to 13%, and analysts see its per-share profit climbing 19% this year. Earnings will grow even more if natural-gas prices rally, but you won’t sweat waiting for that to happen.

|

Southwestern plans to increase 2013 production by 11% to 13%, and analysts see its per-share profit climbing 19% this year. Earnings will grow even more if natural-gas prices rally, but you won’t sweat waiting for that to happen.

LyondellBasell Industries (LYB) Still, Tim Parker of T. Rowe Price says that the narrower profit margins of more commoditized base-chemical companies might see a bigger boost from the new world order of cheaper feedstock and energy. His pick: LyondellBasell. Since the Rotterdam-based company emerged from bankruptcy in April 2010, its New York-listed shares have climbed 184%. The shares, recently trading at $62, fetch 10.7 times 2013 profits. LyondellBasell’s management team is boosting earnings and returning capital to shareholders through share buybacks and dividends. The stock yields 2.6%. And net profit margins of 5.6% trump the 3.7% average of its peers. With new capacity, cheap feedstock and $14 billion in free cash flow, it can earn $10 a share by 2016 and become a $100 stock, Deutsche Bank analyst David Begleiter maintains. Nucor (NUE) The steel industry is vexed by excess capacity, and its volatile stocks surge or slide with temperamental economic data. So it helps that Nucor is more defensive than its peers. Wells Fargo steel analyst Sam Dubinsky favors it over the long haul, “due to its lean cost structure and product diversity, both of which have resulted in earnings at the high head of the peer group.” Nucor also is most levered to the bottoming construction market. A healthy balance sheet and a 3.1% dividend yield further burnish the appeal of its stock, recently at $47.78. Dover (DOV) |

Calpine (CPN)

Calpine is the largest independent U.S. producer of gas-powered electricity, and runs some of the newest, most efficient plants. Just six years ago, nearly half the nation’s power came from coal. But gas’ share has swiftly risen from a fifth to a third, while coal’s has waned.

The ongoing switch to cleaner natural-gas-generated electricity is one reason whyBarron’s has been bullish about the stock (see “Calpine Gets Ready to Light Up,”July 23, 2012). The company also has unused capacity that puts it in the driver’s seat as utilities replace decades-old coal plants.

At first blush, that advantage seems well reflected in the shares, which, at $19, fetch 27.6 times 2013 profit estimates of 69 cents a share. But that seemingly lofty multiple is below its median over the past five years, and Calpine is generating more than $1 a share in free cash flow and continuing to pay down debt. “When power prices are low, Calpine benefits by taking market share from less-efficient producers,” says MacKenzie Davis, who co-manages the RS Global Natural Resources Fund. “But it also benefits if power prices rise, since margins and cash flow will improve.”

Energy can account for nearly 70% of the cost of producing fertilizer, and Jack Ablin, BMO Private Bank’s chief investment officer, singles out CF Industries as a big beneficiary of plentiful natural gas.

The company, which produces nitrogen and phosphate fertilizers, earns 85% of its revenue in the U.S. Shares of Deerfield, Ill.-based CF, at $226, have outrun their peers and climbed 73% over the past two years, the latest leg coming as drought sent corn and soybean prices soaring. Fearful that cyclical earnings have peaked, analysts are downgrading the stock, and investors fret that margins and share buybacks will suffer as management spends $3.8 billion to expand its nitrogen capacity.

But any pullback is an opportunity for long-term investors. Cheap gas costs should keep operating margins near a record 50.1%. Tight corn supplies, low water levels in the Mississippi, and a still-dry Corn Belt should support grain and fertilizer prices, and CF’s investment-grade credit rating and low debt let it borrow money cheaply should it need to. Its stock trades at just 8.2 times what CF earned over the past 12 months, well below the 12.3 times median since it went public in 2005.

Williams (WMB)

So why aren’t American drivers enjoying a bigger windfall at the pump? For one thing, global demand dictates gasoline prices. After decades of ferrying imported oil, our infrastructure also needs to be re-oriented toward redistributing domestically produ

ced na

tural gas. That benefits master limited partnerships that operate pipelines, and for investors who want to avoid MLPs’ complex tax-filing regimes, their parent companies.

Williams gathers and transports natural gas, and owns 78% of its namesake MLP, Williams Partners (WPZ). It has diverse assets, pays a 3.9% yield, and thrives as demand increases for natural-gas processing and infrastructure.

Williams Partners, which sports a 6.6% yield, fell 22%. Shares of its parent also struggled after it issued stock to help finance a complicated $2.25 billion investment in privately held Access Midstream Partners and the MLP it controls.

Still, the deal boosts Williams’ position in the Utica and Marcellus shales, and adds steady fee income that tempers Williams’ exposure to fluctuating commodity prices. Investors fret that Williams, which trades at $34, may have to raise more money, but cash flow of about $1.6 billion this year exceeds the adjusted net income of $816 million that Wall Street expects and should more than cover payouts, letting Williams deliver on its promise to increase dividends at a 20% annual rate through 2015.

Union Pacific (UNP)

All manufactured goods must move from the factories in which they’re made to somewhere else. Kansas City Southern (KSU), which has a unique North-South network linking the Midwest with Mexico, could benefit from any spillover of manufacturing south of our border. But the king of rail remains Union Pacific.

Spawned 150 years ago, after Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railway Act, Union Pacific’s dense network blankets the map west of the Mississippi. Stephens’ transportation analyst Brad Delco flags Union Pacific as one of the rail stocks most exposed to energy-intensive groups like autos, chemicals, and steel. It hugs the Gulf Coast, has the largest U.S. chemical franchise among rail carriers, and hogs 75% of the western U.S. traffic for assembled autos and parts. Its relative absence along the East Coast further shields it from coal’s dying embers.

Union Pacific shares have run up 44%, to $133, over the past two years, nearly twice as much as the rail group has. But the stock trades at 14 times projected profits, a small premium to its peers, and no higher than its own historical average. Management has lifted operating margins to a decade-high 36%. The stock boasts a 2.1% yield, and the company has paid a dividend every year since 1899, when the steam engine propelled the U.S. to its first industrial boom. The rail giant’s in great shape for the next one

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!