A U.S. Manufacturing Comeback Won't Rebuild The Middle Class

During the first half of this year, the trade deficit on trade of manufactured goods narrowed to $225 billion from $227 billion a year ago, the Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation reported Tuesday. While small, the Arlington, Va.-based research group considers the development a positive sign, especially after years of steep deficits.

The report follows another one released Tuesday, which expects U.S. manufacturing to make a comeback — potentially creating 2.5 million to 5 million factory and service jobs associated with more U.S. manufacturing over the next seven years. Boston Consulting Group says the shift is being driven by a variety of factors: Lower costs of natural gas and electricity have given U.S. manufacturers an advantage over other countries; so has the rising cost of labor in China, where the U.S. had lost many manufacturing jobs to.

One other factor — indeed, a big one — that deserves extra attention is the decline of labor costs in the U.S.

While cheaper labor has made manufacturers more likely to hire, it also means less income and spending power for workers.

Understandably many people get nostalgic whenever Washington policymakers and corporate America talk about reclaiming all that was good about U.S. manufacturing during its heyday. It takes us back to a time when the average American could buy a house and raise a family by working at the local factory until retirement. In some ways, the Obama Administration has indulged this vision of America; it has made a manufacturing recovery a top priority.

And yet, it’s hard to get that excited when we look at wages today and where they could go years from now.

A mediocre job is better than no job at all, especially at a time when so many struggle to find work. Manufacturing may create more jobs than it had in recent years, but it won’t renew America’s shrinking middle class so long as wages continue to stagnate.

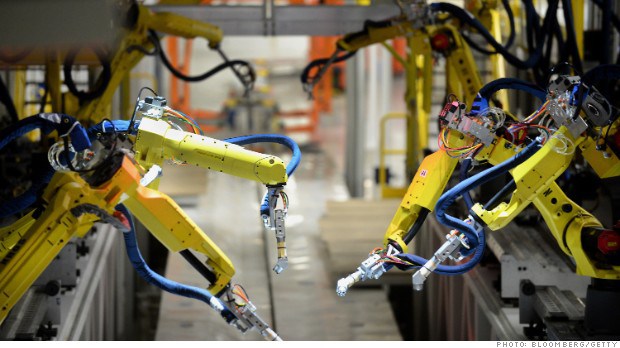

The reality is U.S. factories rely more on machines than actual workers, says Jesse Rothstein, public policy and economics professor at University of California Berkeley. Machines produce more for less, and with bargaining powers of U.S. unions not being what they once were, it becomes less likely workers will earn more.

In a 2012 study, Rothstein found that hires by manufacturers of durable goods (items lasting three years or more) were paid an average of 0.3% less in 2010 and 2011 than workers newly hired in 2007 and 2008.

A similar trend plays out if we look at manufacturing overall: The average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees were $8.43 for 2012, lower than $8.70 in 2009 and $8.75 in 2003, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. To be sure, some higher-skilled manufacturing jobs, such as welding, have seen wages rise.

The Boston Consulting Group notes the U.S. is steadily becoming one of the cheapest places in the developed world to manufacture. By 2015, average labor costs will be about 16% lower in the U.S. than in the U.K., 18% lower than in Japan, 34% lower than in Germany, and 35% lower than in France and Italy.

If the firm is right, it’s likely that many more manufacturers will return jobs to the U.S., as it predicts. However, if trends in pay continue, it probably won’t rebuild the middle class.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!