Why Clothing Startups Are Returning To American Factories

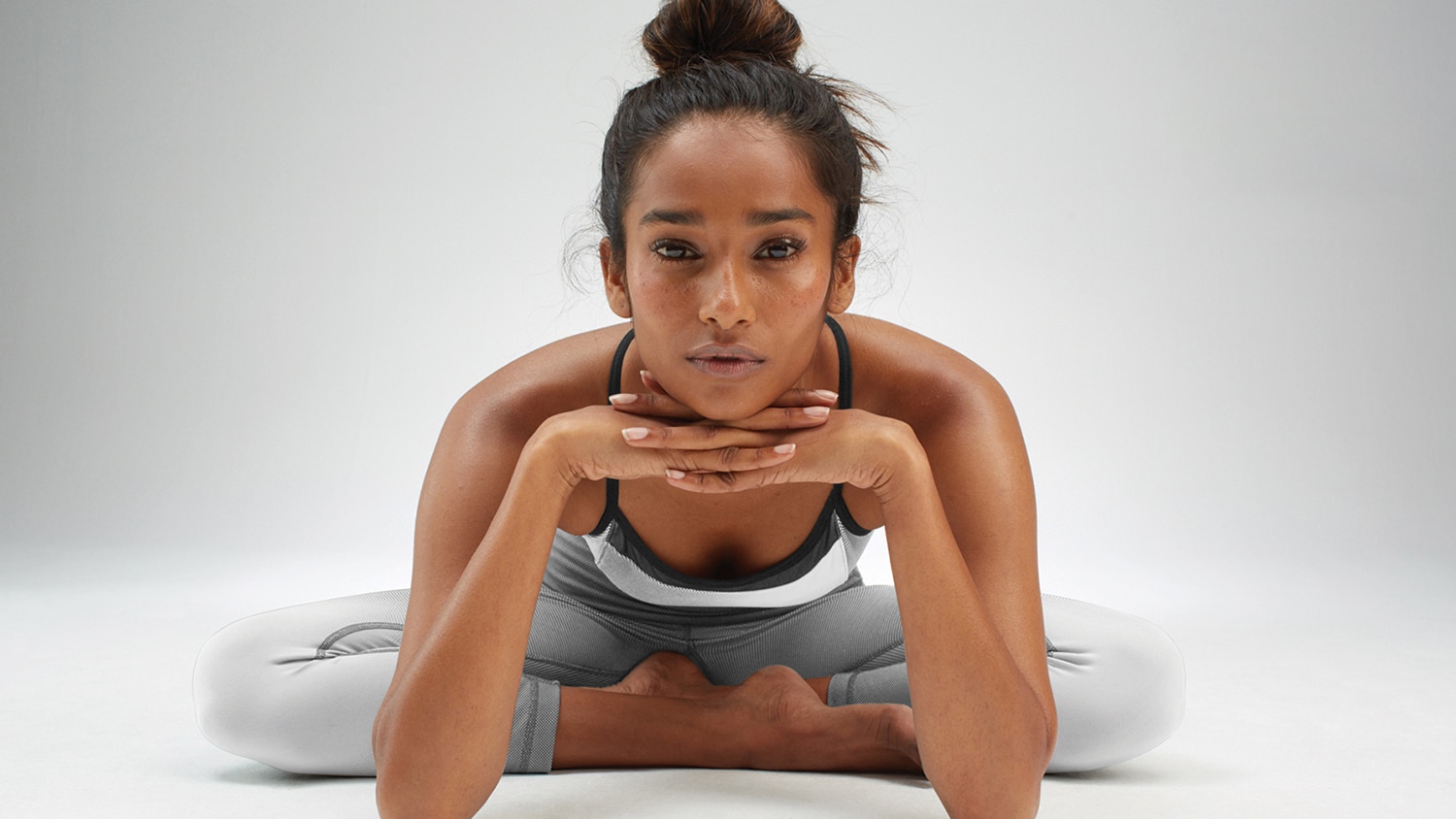

At the swanky Prudential Center in the heart of Boston’s shopping district, the Yogasmoga boutique stands out for its sparse, minimalist aesthetic. At the entrance, there is a large white orchid on a table surrounded by neatly folded tank tops and yoga pants known for their high-tech fabrics. Soothing, Eastern-inspired music is piped in, giving the space a peaceful ambiance.

Yogasmoga’s om-inducing clothes are made 60 miles south of Boston in the gritty town of Fall River, Massachusetts, where I recently met with Yogasmoga’s founder and CEO Rishi Bali to visit the factory. In the 19th century, Fall River was an important textile hub in New England, second in the world only to Manchester, England, in terms of textile production. Over the last few decades, however, the majority of factories in these parts have been shuttered as manufacturing has moved offshore to places such as China and Vietnam where labor is cheaper.

At Griffin Manufacturing, a grand eight-story stone factory built in 1936, this has-been manufacturing hub is showing signs of life. Three floors of this building are in production. While the factory is outfitted with state-of-the-art machines—one, for instance, is able to precisely laser-cut stacks of fabric so that very little goes to waste—it’s surprising how much of each garment is made by hand.

At one station, a sewer named Lee Almeida is stitching a thin layer of piping around the neckline and armholes of a shirt. She says Yogasmoga clothes require more focus because activewear materials tend to curl at the ends, so it is easier to make mistakes. I ask her how long she’s been sewing professionally. “Twenty-four years,” she says, without taking her eyes off the seam she is working on.

When Bali started his company three years ago, his decision to manufacture locally wasn’t motivated primarily by a desire to bring back business to dying factories or to ensure that workers were being well treated. “Of course, as the CEO of a clothing company, I’m haunted by the images of the thousand garment workers who died when the Rana Plaza factory collapsed in Bangladesh,” he says. “I like knowing that that won’t happen here. But it’s also true that I simply couldn’t produce the clothes I wanted to make overseas.” This is a sharp turn from a company like American Apparel, which opened in 1989, advertising its American-made products as an alternative to those made in sweatshops in Asia.

Bali wanted to create his own technical fabrics, monitor quality, and have the flexibility to scale up his business as quickly as possible. He believes the only way he was able to accomplish these goals was to set up production in the U.S. And this decision is paying off: Last year, the company had a valuation of $78 million and opened its 12th store. “It can take 10 months to go from placing an order at a Chinese factory to receiving a shipment of clothes,” Bali says. “By using local factories, I’m able to meet demand much quicker.”

HIGH-TECH FABRICS

Two years before launching Yogasmoga, it occurred to Bali that a large proportion of yogawear on the market is made of nylon and spandex, both of which are very dated fabrics, invented by DuPont in 1938 and 1958, respectively. And even though he had spent his career at Goldman Sachs and didn’t have a lick of textile manufacturing experience, he wanted to see exactly how hard it would be for him to develop new materials that would be ideal to wear for the practice of yoga.

That search led him to Invista, a company spun-off by DuPont in 2003, which develops synthetic fibers. “It turns out that while many companies are still using nylon in their clothes, there has been a huge amount of technological advancement in textiles,” Bali says. However, developing new fabrics is expensive and requires a lot of time collaborating with specialty companies like Invista, which is why it is easier to rely on existing synthetic materials that are abundant and cheap.

He’s spent the last few years working closely with Invista, testing out how different combinations of fibers feel and perform when they come together. Supplex, for instance, is a synthetic fiber that manages to create the feeling of wool, but has the added benefits of wicking moisture, stretching, and not pilling or losing its color when washed. Tactel, another synthetic fiber, is lightweight but extremely durable, and it dries eight times faster than cotton. Bali eventually worked with scientists to create 30 different technical fabrics that use various combinations of synthetic and organic fibers to create specific effects—yoga pants that feel soft as wool but that don’t trap heat, sports bras that feel like silk but can stretch, prints whose colors don’t fade. “I felt like I needed to be deeply involved in this process,” Bali says. “This is our intellectual property as a company.” (He now has a team of five in-house textile experts who work with designers to develop new fabrics for each season.)

Bali explains that it would have been impossible to manufacture these garments overseas. Asian factories would not have had the infrastructure to produce these brand new fabrics: Bali had to source out a speciality mill in California to turn the Invista fibers into cloth. And on a basic level, communication would have been a challenge, especially given that Asian factories would never have encountered the fabrics he had just invented. If there were issues with quality, he would not have been able to spot them until too late, which might result in a lot of expensive fabric going to waste.

Which brings us back to Lee Almeida, the sewer in the Fall River factory. Bali has discussed the specific qualities of each fabric with the factory manager who has, in turn, explained everything to the 40 workers, who all speak English. Almeida is fully aware about how best to handle Yogasmoga fabrics in the sewing process, even though it is entirely new to her. She knows exactly how much tension to use as she stretches them out to sew a hem. And Bali is able to check in at the factory every month to ensure the quality of the final garments are up to snuff.

THE AMERICAN-MADE TIDE TURNS

Bali is part of a nascent trend of clothing startups bringing business back to American factories. Over the past two decades, there was a 90% decline in apparel manufacturing industry in the U.S., from 940,000 jobs in 1990 to 136,000 in 2015. This has been in part due to the Trans-Pacific Partnerships, which provide incentives such as lower tariffs for companies that want to produce clothes overseas—though the merits of free trade have been hotly contested in this election cycle.

“There is something cool about . . . disproving what we’ve been told for the last 40 years about how American manufacturing is dead.”

Recently, however, something interesting has happened. “After a mass exodus of manufacturing jobs overseas, we stopped losing jobs in 2012—and local manufacturing began to remain stable,” says Bob Bland, founder and CEO of Manufacture New York, an organization that helps fashion startups create their products in New York City. “This is the first victory for those of us committed to manufacturing locally.”

Part of this shift can be attributed to the clothing startups that have started moving back into American factories instead of instinctively going overseas. Bland also believes that these numbers underestimate how much work is being done in the U.S. because many fashion designers and artisans are not being counted by Bureau of Labor Statistics. “The maker movement has happened during the last few years, and not all makers consider themselves industrial manufacturers,” she says.

For fledgling companies, there are some benefits to starting locally. While clothes cost less per unit to manufacture overseas, you need significant capital to even begin production. This is what Sasha Koehn and Erik Schnakenberg discovered when they decided to launch the Los Angeles-based menswear label Buck Mason in 2014. Their goal was to produce American-made basics: simple T-shirts, jeans, and button-downs. “We each put in $5,000 and found a local factory in L.A. to make our first run of T-shirts,” Schnakenberg recalls. “That entire budget would have been eaten up on our plane ticket to China. But the way we did it, we were able to design and sell our first products.”

By selling those initial products online, they were able to start making others. By year two, they were pulling in several million dollars in sales and opening their first physical store. (They’re on to their second store this year.) They admit that their margins are higher than they would be if they went overseas—but their margins are not too shabby, either. It costs them $16 to make a T-shirt that sells for $24. “We’ve spent hardly any money on marketing, relying instead on word of mouth to get our products out there,” he says. “This has cut down on our costs, and we’ve still been able to grow exponentially.”

Kate Bowen and Ashley Wayman, the women who launched children’s wear brand Petit Peony a year and a half ago, have a similar experience. They explored local factories to see what the minimum order was to start production. They ended up at Griffin, the same factory that Yogosmoga uses, where they only needed to purchase 1,000 units in each print and size to secure a contract. This was far more manageable than overseas factories requiring orders in the tens of thousands.

The founders of these startups certainly appreciate the moral reasons for manufacturing locally. “As a children’s clothing company, we could not risk the possibility that our clothes could be made by underaged workers—children, really—who were being exploited,” Wayman says. Schnakenberg also points out that while manufacturing locally allows him to visit factories to check on quality, it allows him to ensure that workers are well treated and paid decently. “What we’ve discovered is that the further the brand is from the manufacturing physically, the more difficult it is to manage it and ensure that there is an ethical process in place,” he says. “When we approached this from an idealistic, but also entrepreneurial perspective, we discovered that it is definitely possible to have a profitable business while making clothes here in America. We can create jobs while also creating a thriving and smart business.”

CAN AMERICAN-MADE GO MAINSTREAM?

While small startups are finding some immediate benefits to creating products in local factories, manufacturing in the U.S. can only begin to compete with overseas manufacturing in terms of quality, speed to market, and even cost, when they are able to scale up. One good example of this is American Giant, a four-year old company founded by Bayard Winthrop, known for creating durable American-made sweatshirts that have garnered a cult following.

Winthrop has observed that while manufacturing abroad drives down labor costs, it also requires companies to mark up their products because a significant chunk of their inventory will never get sold—some products will be discarded because of poor quality, slow turnaround time means that some clothes will no longer be fashionable when they reach stores, and designers often make bad bets on color schemes or patterns and aren’t able to withdraw orders.

He makes the case that when a company is large enough to start investing in a U.S.- based supply chain, it can cut down on this waste and keep prices affordable for customers. For his part, Winthrop has recently moved the vast majority of American Giant production to North and South Carolina. “Once you have scale, you can control and mitigate inventory risks dramatically, allowing you to charge a much fairer retail price,” Winthrop says. “You begin to unlock a lot of big picture efficiencies that, we would argue, are beginning to reset assumptions in the industry about the competitiveness and effectiveness of American-made products.”

American-made products will never be as cheap as the $3 T-shirts sold at H&M or Primark, the British fast-fashion store that has recently arrived in the U.S. American Giant sweatshirts cost around $90, which places them on par with those at Banana Republic or J.Crew. However, CEOs who make products locally argue that customers are getting much better value. “When you consider weight, quality, construction, and hardware, I don’t think we could do this more cheaply if we were making it in China,” Winthrop says. Bali, whose yoga pants begin at $84, makes a similar argument. “While our prices are on par with our competitors who make their products in Asia, our customer is getting a superior product in terms of quality and materials,” he says.

Of course, not all startups are able to grow as quickly as American Giant and Yogasmoga, and therefore take advantage of the economic efficiencies that occur at such a large scale. This is where Manufacture New York hopes to make a difference. Based in a factory in Brooklyn, the organization helps up-and-coming designers understand the production process and tap into a local supply chain. Designers work alongside engineers, textile specialists, sewers, and other manufacturing experts to find ways to create products at reasonable prices. Manufacture New York has already launched more than 90 labels that are able to benefit from the scale that Winthrop is talking about.

Companies committed to manufacturing locally are innovating at the level of fabric and design, but they also have to be creative in terms of the entire supply chain. For instance, Manufacture New York’s Bland is keen to find a way to improve the process of picking out garments in a warehouse and packing them when a customer makes an order. This is a laborious process that is still largely done by hand, but she believes it can be automated. Bali and Winthrop spend their days cracking logistical puzzles like how to shave off minutes on transporting fabrics from mills to factories or how to maximize each swath of fabric when cutting clothing patterns.

While there are plenty of challenges with making products in the U.S., finding solutions to these hard problems is also what seems to make these companies tick. “Is there a moral calling? I don’t think there is. Jobs in Shenzhen [China] are just as important to the families in Shenzhen as they are to American families,” Winthrop says. “But there is something cool about the fact that American-made clothing companies are disproving what we’ve been told for the last 40 years about how American manufacturing is dead.”

Source: Fast Company

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!