Factory Jobs Flow Back to America: China’s rising costs spark sea change in manufacturing

The move is part of a sea change in American manufacturing: After three decades of an exodus of production to China and other low-wage countries, companies have curtailed moves abroad.

Some, like Generac, have begun to return manufacturing to U.S. shores.

Although no one keeps precise statistics, the retreat from offshoring is clear from various sources, including federal data on assistance to workers hurt by overseas moves.

U.S. factory payrolls have grown for four straight years, with gains totaling about 650,000 jobs. That’s a small fraction of the 6 million lost in the previous decade, but it still marks the biggest and longest stretch of manufacturing increases in a quarter of a century.

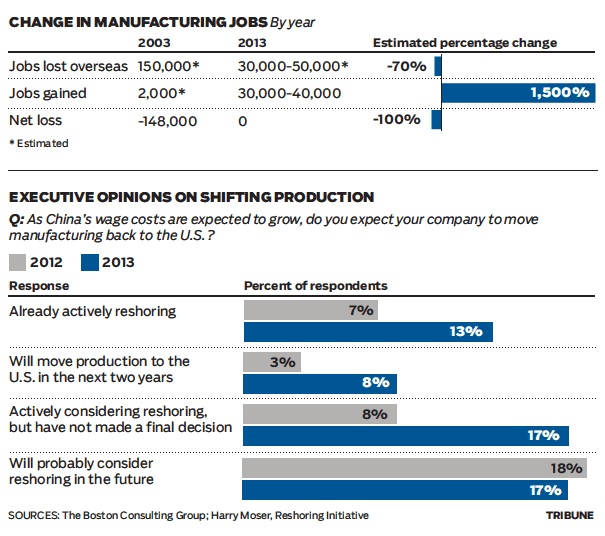

Harry Moser, an MIT trained engineer who tracks the inflow of jobs, estimates that last year marked the first time since the offshoring trend began that factory jobs returning to the U.S. matched the number lost, about 40,000 each.

“Offshoring and ‘reshoring’ were roughly in balance — I call that victory,” said Moser, who traces his interest in manufacturing to his parents’ work at the long-closed Singer Sewing Machine plant in New Jersey. (He once worked there too.) He now runs the Reshoring Initiative, a Chicago nonprofit that works with companies to bring manufacturing jobs back to the U.S.

Several factors lie behind the change.

Over the past decade, Chinese labor and transportation costs have jumped while U.S. wages have stagnated. Manufacturing also has become more automated, further reducing labor’s weight in the cost equation.

The boom in natural gas production in the U.S. has led to a 25 percent decrease in gas prices in the U.S., contrasted with a 138 percent increase in China, according to The Boston Consulting Group.

Many U.S. manufacturers also report growing problems with quality control of goods made in China. “We got to the point where everything we were bringing in had to be inspected,” said Lonnie Kane, president of apparel-maker Karen Kane, noting that his company used to check just 10 percent of goods from China.

“Now prices are escalating, quality is dropping and deliveries are being delayed,” he says. In the past three years, Kane has shifted 80 percent of his production from China back home.

Expansion in the domestic apparel industry remains unusual because the labor-intensive work can be done in many low-wage countries.

But in other industries, a growing number of domestic and foreign companies — including General Electric, Caterpillar, Toyota and Siemens — are opting to build or expand their facilities in the U.S., particularly in the Southeast, where labor costs are low.

For the first time, some small contract manufacturers in the U.S. are beating bigger rivals in Asia, the center of global industrial production.

At Zentech Manufacturing in Baltimore, the company’s president, Matt Turpin, recalls his skepticism when salesmen told him two years ago about their efforts to land a contract making 5,000 to 10,000 wireless printers. He was sure an overseas competitor would get the work.

“I don’t know why you’re wasting your time chasing that business,” he says he told the sales force.

Zentech ultimately won the contract, and Turpin says the company added at least five full-time employees to his shop, where the front office window is draped with a large American flag.

William Davidson, a test technician at Zentech, now earns $17.50 an hour working on those printers and other company products. Before getting hired at Zen-tech three years ago, Davidson, 62, had been unemployed for 18 months. His previous employer, a Delaware repairer of cable boxes, had moved its operations to Mexico.

“The worst part of it was we had to help them pack things up for the move,” he says.

The offshoring “didn’t feel right” because of the families affected by layoffs, he said, but the company needed to make the move to remain competitive.

Generac grew rapidly over most of the rest of the decade. Its sales rose to $1.5 billion last year, and it now has about 3,300 workers, including 720 in Whitewater, its largest plant. But the past decade also saw costs surge in China while they rose little in the U.S.

What began as a $100 gap in the cost of producing an alternator narrowed as the Chinese yuan jumped in value and Chinese wages and other costs soared.

The tipping point came when Generac had enough sales to justify investing millions of dollars in new equipment for the Whitewater plant. The company can now produce an alternator with one worker in the time it took four workers in China.

Too little too late for my small contract manufacturing shop. We did everything we could in the past ten years to stay in business and we did. But at an expense of low wages, including mine, not collecting rent on the building we own, etc. We have given up. We have already sent our customers letters letting them know we are going out of business. 60 years in business down the drain. It’s over for the manufacturing in the USA and soon as you can accept that fact the better you can plan for the near future financial meltdown.