Made in America: Why American Giant Didn’t Want to Build Factories in China

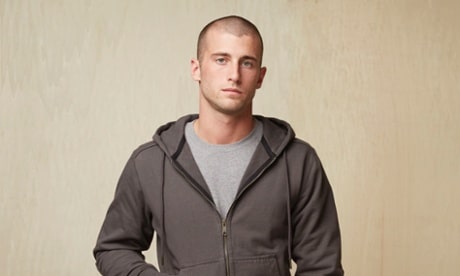

American Giant: Made in America.

With the prevalence of outsourcing factory work to Bangladesh and China, fewer retailers can use those three short words on popular clothing.

Three years into its existence, American Giant is sticking to US production and predicting that its retail-store rivals are under “dire, dire threat”

There is one who thought of going the China route, then turned back to Made in the USA: Bayard Winthrop, founder of American Giant.

American Giant sweatshirts are the darlings of Silicon Valley techies. After Farhad Manjoo, then a writer for Slate, wrote a piece heralding Winthrop’s sweatshirt as the “greatest hoodie ever made”, the company sold out of its entire stock within 36 hours. After a few months, the company increased its production capacity 15 to 20 times what it was previously and the greatest hoodie ever made was back in stock.

It’s a fallacy, Winthrop says, that in order to purchase a Made in America product consumers either have to sacrifice quality or put up with high prices. When he considered factories in China, “I realized I was chasing the cheapest material, the cheapest labor,” he explains to the Guardian.

With main offices in San Francisco and staff of about 23, Winthrop works with five US-based factories to make basic wear like sweatshirts, shirts and now even sweatpants. Two of the factories are based in California, three in North Carolina.

“People want to buy Made in America products,” says Winthrop. “Sweatshirts, particularly, are an iconic American wear and no brand had owned or done a particularly good job with it”.

North Carolina “is still a million times easier than Shenzen,” he has told reporters.

This stance is surprising in our era of gleeful corporate outsourcing, but perhaps not a shock coming from Winthrop himself, who is descended from several American giants himself. Although he never mentions it, Winthrop’s family counts itself among the original Puritan English migrants who established the city of Boston. His forebears helped found the Massachusetts Bay Colony, starting with John Winthrop, who was described as a “Freedom Man” by Ronald Reagan; subsequent Winthrops were civil war generals and prominent bankers. Even though he did not grow up with that side of the family, American patriotism might reasonably be expected of him.

Despite this when Winthrop launched his company in early 2012, he wasn’t answering one of the many calls from Barack Obama to create more Made in America products. He had a “one of those learning moments, just out of the blue,” that creating sweatshirts in foreign factories would undermine the company’s “brand values and quality.”

“Consumers were learning about brands in a fundamentally new way. They were telling friends about it. They were communicating via social word of mouth. Print ads were being replaced,” he explains. “People were pulled in not by huge full-page ads, but by word-of-mouth. Consumers were saying that they are increasingly trusting their peers to tell them about what’s happening out there.”

We caught up with Winthrop to talk about running a Made in America company and all that that entails.

Did you ever imagine that you would be running and managing a clothing company?

I grew up in a family that had a pretty well-off father and a mother that was not well-off. My parents divorced when I was young and my dad paid for my education, but not much else. I had a pretty gold-plated New England-education but at home, it was different. I think I was aware of that at the time – but looking back at that, it gave me a certain amount of drive and passion about wanting to prove myself financially.

Right out of college, I ended up going into corporate-finance, investment banking and Wall Street stuff, but I pretty quickly, in that process, met business leaders and found myself getting energized and inspired by the businesses that we were watching. At that point, I knew that I wanted to be running a business. I was very interested in making things and so I knew I wanted to be in manufacturing business.

One thing I will say, I grew up in the 70s and my mom on her budget was able to buy me a US-made sweatshirt that was of the best quality in the world, that she could afford. It would last forever. And 40 years later, when you got an iPhone in your pocket that can play every song, do a conference call, order you a car, buy you groceries, we no longer as a nation have the ability to make that sweatshirt in the US. I always had a bit of chip on my shoulder about that. There is so much pressure on manufacturers, cost cutting, on US laborers, but no one has stepped back and taken a critical look at where all of the “spend” is.

I was always sort of annoyed and aware of that, but I don’t think I ever said that I am going to one day make a ‘Made in America’ a viable business model.

Would you say that having a background in corporate finance helped with starting your own business?

I think it helps tremendously. It builds understanding of how important financials are, but also that was a particularly vigorous and demanding job to have right out of college. It taught me quickly to work hard, to work accurately, to know what you are talking about.

Is it easy to communicate your values to your staff? Does your culture support that?

An interesting thing happens organizationally when you simplify an organization. A company like Abercrombie & Fitch, for example, which has huge marketing disciplines, huge real estate disciplines, huge supply chain disciplines, one of the hallmark of these commerce business is that they can have much linear organization with people focusing on a narrower set of things that are critical to the businesses and making the business really go.

The staff working at American Giant is intimately involved with really either product or customers. The way that we communicate with our people, we really empower folks. We basically have an internal pride in the organization as a whole. There is maximum value to our customers, strip away everything else.

The empowering and the ability to make these decisions gets pushed down in the organization. My customer service team is completely empowered to override a replacement sweatshirt if the customer gets the sweatshirt in the wrong color. Or they send a gift certificate as a thank you for supporting us.

There is an awful lot of employee empowerment that allows the people at American Giant to be directly responsible for how we do as a company. There’s lot of real sense of pride, ownership and clarity in what we do.

You had your mini-Oprah moment when Farhad [Manjoo] wrote a piece about your sweatshirt, calling it the greatest hoodie ever made and you saw an significant increase in demand for your product. You sold out in 36 hours. What did you learn from that experience?

It was in December of 2012 … What the piece did, it definitely got us a lot of awareness around the business. But most importantly than that, it pushed us along to consumers and media about our business model and the product. It had an impact of growing the business significantly.

But also, the impact of having the media sort of say ‘Gee, American manufacturing is something that is viable now, it could be a new commerce model.’

We had to go and make something in the United States and sell it at the same retail price as Abercrombie & Fitch sweatshirt for a much better quality. ‘Is that even possible?’ You had people asking if the product is as good as he says it is.

I think he wrote that one line:

I didn’t just write about American Giant. I turned down the lights, put on some Barry White, and, over the course of around 2,000 gyrating words, unspooled my sweet, tender love for the company and its clothes.

I was debating quoting that exact line at you …

That comment, it had a lot of consumers saying: ‘Is this that good?’ It kicked off a lot of interesting discussions.

For me, it did two things: from a volume standpoint, it made us say: how can you predict demand in an unpredictable, vast and scary environment?

The other thing it did for us: it made really clear to us that if you stick to your principles to build a great product, you stand for something – in our case that meant make it in United States and keep retail prices reasonable so that you can reach mainstream consumer – and you can get very big.

The inverse of that was: don’t get distracted. Focus on what you do well. Keep doing it. Keep true to your customers, and if you do that they will take care of you and they will spread the word and have people like Farhad say great things.

What’s next for American Giant?

We believe that we are entering into a phase of macro-level where you are going to see a lot of fundamental disruption in the apparel retail. There are a few things at play. One is that a lot of the old retail businesses – like Aeropostale and Abercrombie & Fitch and all these guys – they are burdened by massive real estate and marketing budgets that customers are not caring about. Many of those businesses are in a gradual and accelerating decline, the same way that Blockbuster, Tower Records, Borders Books were before that. They are under a dire, dire threat.

On the other side, we are seeing an explosively growing [ecommerce] businesses – America Giant, Nasty Gal, Warby Parker. We are the clear and fastest moving player in netwear basics category and we intend to own that.

What is the one piece of advice that you would give to someone hoping to start their own businesses?

The best way to start a company is to start it. I believe that. If you can make the finances work, as long as you figure that piece out, do it. If you have conviction, if you have passion, go. You got to get going. You have to get the board in the water.

The other really really important thing is, I think a lot of entrepreneurs fail because they can’t decide what are the two or three critical things they have to do are and they don’t have the conviction and the courage to ignore everything else. That’s a really tough skill, a really aggressive triage. You are sort of always thinking about: What are they not going to like? How can we make things better? You have to have the conviction and the fortitude to say I am not going to do that. That’s not the critical path I need to take right now. Having to decide what not to do is pretty important.

SOURCE: The Guardian

Thank You keep up the GREAT work. I have always tried to wear everything American made but in the last few years no luck finding it.