Chinese Textile Manufacturers Bring Jobs Back to America

Twenty-five years ago, Ni Meijuan earned $19 a month working the spinning machines at a vast textile factory in the Chinese city of Hangzhou.

Now at the Keer Group’s cotton mill in South Carolina, which opened in March, Ms. Ni is training American workers to do the job she used to do.

“They’re quick learners,” Ms. Ni said after showing two fresh recruits how to tease errant wisps of cotton from the machines’ grinding gears. “But they have to learn to be quicker.”

Once the epitome of cheap mass manufacturing, textile producers from formerly low-cost nations are starting to set up shop in America. It is part of a blurring of once seemingly clear-cut boundaries between high- and low-cost manufacturing nations that few would have predicted a decade ago.

Textile production in China is becoming increasingly unprofitable after years of rising wages, higher energy bills and mounting logistical costs, as well as new government quotas on the import of cotton.

At the same time, manufacturing costs in the United States are becoming more competitive. In Lancaster County, where Indian Land is located, Keer has found residents desperate for work, even at depressed wages, as well as access to cheap and abundant land and energy and heavily subsidized cotton.

Politicians, from the county to the state to the federal government, have raced to ply Keer with grants and tax breaks to bring back manufacturing jobs once thought to be lost forever.

The prospect of a sweeping Pacific trade agreement that is led by the United States, and excludes China, is also driving Chinese yarn companies to gain a foothold here, lest they be shut out of the lucrative American market.

Keer’s $218 million textile mill spins yarn from raw cotton to sell to textile makers across Asia. While Keer still spins much of its yarn in China, importing the raw cotton from America, that is slowly changing.

“The reasons for Keer coming here? Incentives, land, the environment, the workers,” Zhu Shanqing, Keer’s chairman, said on a recent trip to the United States.

“In China, the whole yarn manufacturing industry is losing money,” he added. “In America, it’s very different.”

Since Beijing and Washington resumed trade relations in the early 1970s, the United States has mostly run a huge trade deficit, as Americans consumed billions of dollars in cheap electronics, apparel and other Chinese goods.

But surging labor and energy costs in China are eroding its competitiveness in manufacturing. According to the Boston Consulting Group, manufacturing wages adjusted for productivity have almost tripled in China over the last decade, to an estimated $12.47 an hour last year from $4.35 an hour in 2004.

In the United States, manufacturing wages adjusted for productivity have risen less than 30 percent since 2004, to $22.32 an hour, according to the consulting firm. And the higher wages for American workers are offset by lower natural gas prices, as well as inexpensive cotton and local tax breaks and subsidies.

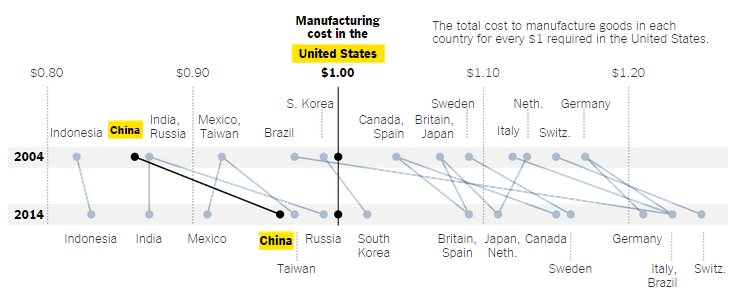

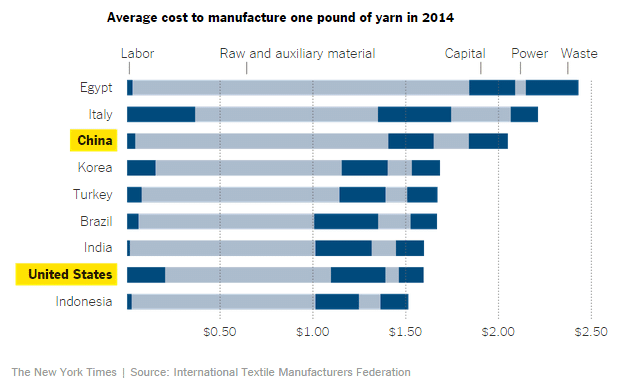

Today, for every $1 required to manufacture in the United States, Boston Consulting estimates that it costs 96 cents to manufacture in China. Yarn production costs in China are now 30 percent higher than in the United States, according to the International Textile Manufacturers Federation.

“Everybody believed that China would always be cheaper,” said Harold L. Sirkin, a senior partner at Boston Consulting. “But things are changing even faster than anyone imagined.”

Rising costs in China are causing a shift of some types of manufacturing to lower-cost countries like Bangladesh, India and Vietnam. In many cases, the exodus has been led by the Chinese themselves, who have aggressively moved to set up manufacturing bases elsewhere.

Chinese Textile Mills Hiring in Places Where Cotton Was King

In recent years, the United States has started to get more attention from that exodus. From 2000 to 2014, Chinese companies invested $46 billion on new projects and acquisitions in the United States, much of it in the last five years, according to a report published in May by the Rhodium Group, a New York research firm.

The Carolinas are now home to at least 20 Chinese manufacturers, including Keer and Sun Fiber, which set up a polyester fiber textile plant in Richburg, S.C., last year. And in Lancaster County, negotiations are underway with two more textile companies, from Taiwan and the Chinese mainland.

“I never thought the Chinese would be the ones bringing textile jobs back,” said Keith Tunnell, president of the Lancaster County Economic Development Corporation, who helped put together subsidies for Keer estimated at about $20 million, including infrastructure grants, revenue bonds and tax credits.

The inner workings of Keer’s factory in Lancaster County help demonstrate why yarn can now be produced for such a low cost in the United States and point to the kind of capital-intensive manufacturing that could thrive again in America.

Inside the 230,000-square-foot spinning textile plant, giant machines help clean the seeds and dirt from the cotton and send the fluff into carding machines that assemble the cotton into thick, long ropes of fiber. Workers then feed the ropes into machines that spin the cotton into spools of yarn or thread.

The work is highly automated, with the factory’s 32 production lines churning out about 85 tons of yarn a day. Even when Keer opens a second factory next year, it will hire just 500 workers, a fraction of the thousands of workers who toiled at cotton textile mills across the South for much of the 19th and 20th centuries — a big reason Keer is able to keep costs down.

The Rising Cost of Manufacturing

The spools of yarn are then shipped through the port of Charleston to textile and apparel manufacturers across Asia. Keer also hopes to sell to apparel manufacturers in Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, where many nations enjoy privileged access to the American market as part of separate trading pacts — as long as the yarn is made in a member country.

Sheng Lu, an apparel and textiles expert at the University of Rhode Island, said the high capital intensity of modern yarn-spinning meant that American mills were becoming increasingly competitive.

“Common sense says that the U.S. imports textiles and apparel from China,” he said. “Now some of that is reversed.”

But cutting and sewing clothes, he said, still relies so much on labor that “it’s just impossible for the U.S. to be competitive.”

Investment in American textile has not come just from China. Last year, the ShriVallabh Pittie Group, a leading textile manufacturer in India, broke ground on a $70 million textile factory in Sylvania, Ga., the area’s first new manufacturing plant in four decades. And Santana Textile, a large Brazilian denim manufacturer, announced in 2012 that it would open a spinning, dyeing and weaving facility in Edinburg, Tex., though full-scale production has been delayed.

“The whole textile world is looking at us,” Vinod Pittie, chairman of the ShriVallabh Pittie Group, said at the factory’s groundbreaking ceremony, predicting that the success of the venture would draw other entrepreneurs to open plants in Georgia.

For residents of South Carolina, Keer’s arrival could not have come soon enough. A generation of weavers and spinners lost their jobs when Springs Industries, which once ran some of the world’s biggest cotton mills in the city of Lancaster, closed its last plant in 2007, selling off its machines to a company in Brazil.

The global economic crisis hit soon afterward. By June 2009, Lancaster County’s unemployment rate had reached 18.6 percent.

“They shut them down one by one,” said Donnie R. Gordon, who spent 17 years weaving cotton at Springs Industries until he was laid off in the 1990s. He now works in maintenance for the Lancaster County school system. “You could make good money at the textile mills, but those jobs just went away.”

But shrinking manufacturing jobs have spurred a willingness in places like Lancaster County to work for lower pay, making them increasingly attractive production bases. Global manufacturers have also been drawn to so-called right-to-work states like South Carolina, where there is little unionization.

“I think I’m going to like it here,” said Enabel Perez, a former apparel factory worker and one of Ms. Ni’s trainees. Ms. Perez said she had jumped at Keer’s call for workers, an event welcomed in Lancaster County with a segment on the evening news.

Keer’s gamble in America is not without risks. The strong dollar, for one, has added to the costs of producing in the United States. Water shortages in Arizona and California could also threaten cotton production, as well as jeopardize already endangered cotton subsidies.

The outcome of stalled negotiations over the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a free-trade agreement that leaves out China, will also affect Keer’s American prospects. American negotiators are pushing for rules that would require apparel makers in member countries to use yarn from within the trade zone to enjoy tariff reductions. By producing yarn in America, Keer is hedging its bets, making sure it can continue to supply yarn to apparel manufacturers to countries like Vietnam that are within the T.P.P. trade zone.

Then there are the cultural differences. Ms. Ni, one of 15 Chinese trainers at Keer’s Indian Land plant, complained softly of American workers’ occasional tardiness. In China, she said, managers can dock the pay of workers who show up late. But here, she said, she felt frustrated that she could not discipline tardy staff.

Robbie Sowers, 44, a textile industry veteran who maintains the plant’s spinning machines, called such differences minor. He said Keer managers had started giving workers six minutes’ leeway before calling them late.

“There’s a lot of talent and experience here in South Carolina,” he said. “It’s just a matter of getting used to the American way of working.”

As she walked through the textile factory floor, Ms. Ni pointed to digital screens at the end of each row of spinning machines, which displayed in real time, out of a score of 100, how efficiently those machines were kept running by their operators. The screens flashed: 76, 85, 90. Experienced workers in China rarely let that number drop below 97, she said.

“They’re learning,” she said. “I have to be patient.”

SOURCE: New York Times[p][/p]

An article on Monday about a Chinese yarn manufacturer’s opening of a cotton yarn mill in South Carolina misstated the month the mill opened. Operations began in March, not April. The article also misstated the age of Robbie Sowers, a mill worker. He is 44, not 32.[p][/p]

Because of an editing error, an earlier version of a picture caption with this article misstated the age of Robbie Sowers, a mill worker. He is 44, not 32. Also because of an editing error, an earlier version described incorrectly his history in the textile industry. He is a 44-year-old industry veteran, not a 44-year veteran.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!