This Factory is Where Trump May Draw The Line on Trade

When Bill Hughes went to fight in Iraq in 2003, members of his Army unit lined their vehicles with scrap metal, sandbags and bulletproof vests to protect themselves from roadside bombs. By the time his younger brother Ryan Young was in Iraq in 2008, the vehicles were made of a high-purity aluminum alloy that was much more effective at absorbing the blast.

“At the beginning of the Iraq War, the Humvees were folding up like pop cans,” Hughes said. “It was a really big deal until they started putting the different metals in.”

Today, Hughes and Young work side by side here at the last U.S. smelter that makes the high-purity aluminum used in armored vehicles, sons of a region where jobs in the metal industry, ubiquitous for decades, have become a rapidly disappearing way of life. Hawesville’s Century Aluminum Co. plant constantly teeters on the edge of shutting down, typical in an industry where a glut of cheap metal from China has forced many plants to close.

But hope came to Hawesville in April, when President Trump announced that his administration was considering restricting imports of foreign-forged aluminum in the name of national security, arguing that domestic plants needed to be protected to ensure that the country can make its own war machines. “When that come out, there was a buzz in the area. You could just see the excitement on people’s faces,” said Hughes, 34.

A decision by the Trump administration to use national security to protect an industry would be among the most dramatic — and risky — moves in the president’s trade agenda, which seeks to limit what he regards as unfair foreign competition. While intervention could be a boon for Hawesville, it could raise prices for other customers and companies — including the federal government, which ultimately buys the armored vehicles and fighter jets made from the aluminum.

And amid the debate over how far the government should go to protect certain industries in the era of global competition and technological change, some trade and industry experts are questioning whether the administration is simply using national security as an excuse for economic protectionism. The decision — based on a Commerce Department investigation — will come out in June, Trump said in a tweet Saturday night. “Will take more action if necessary,” he wrote.

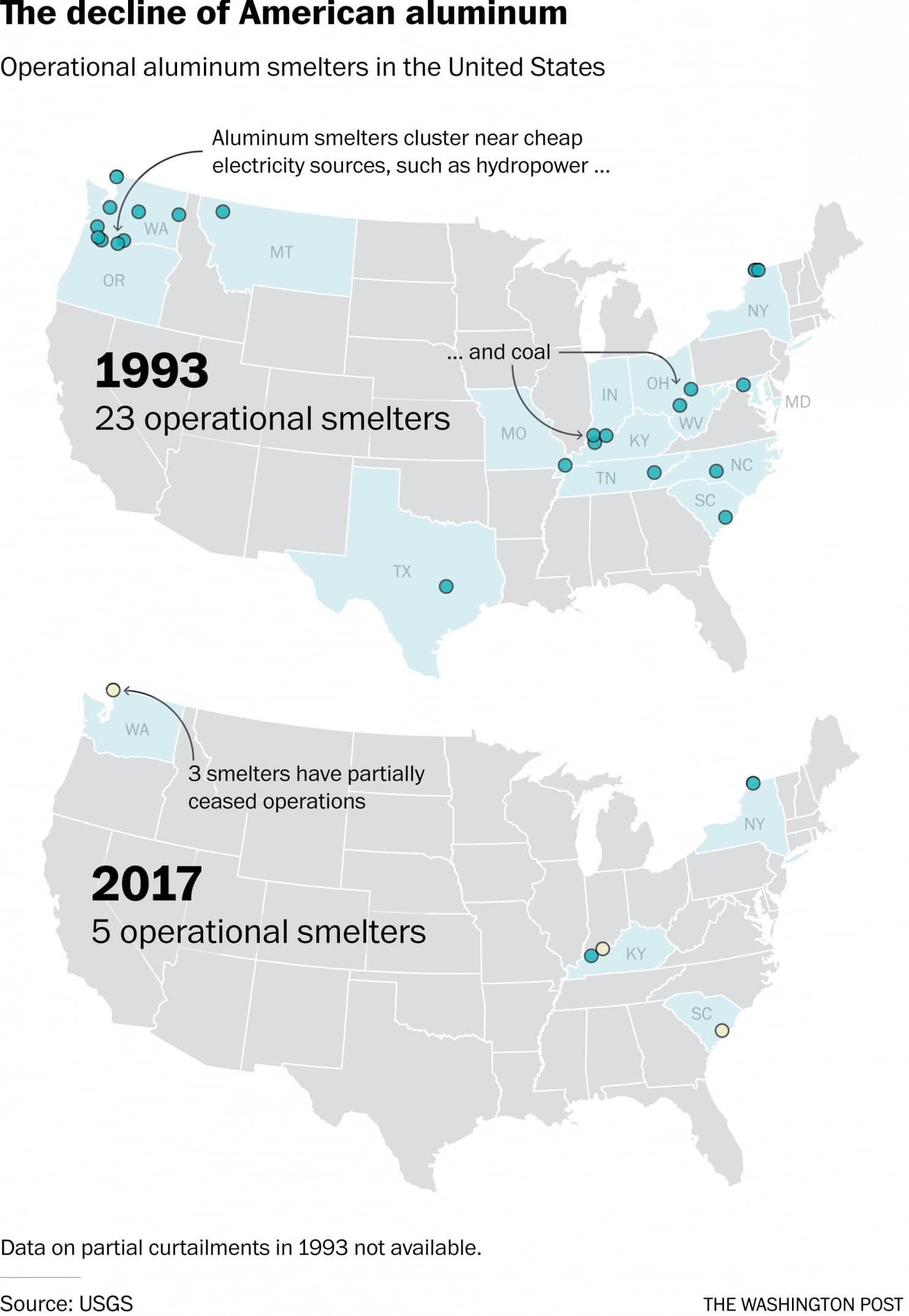

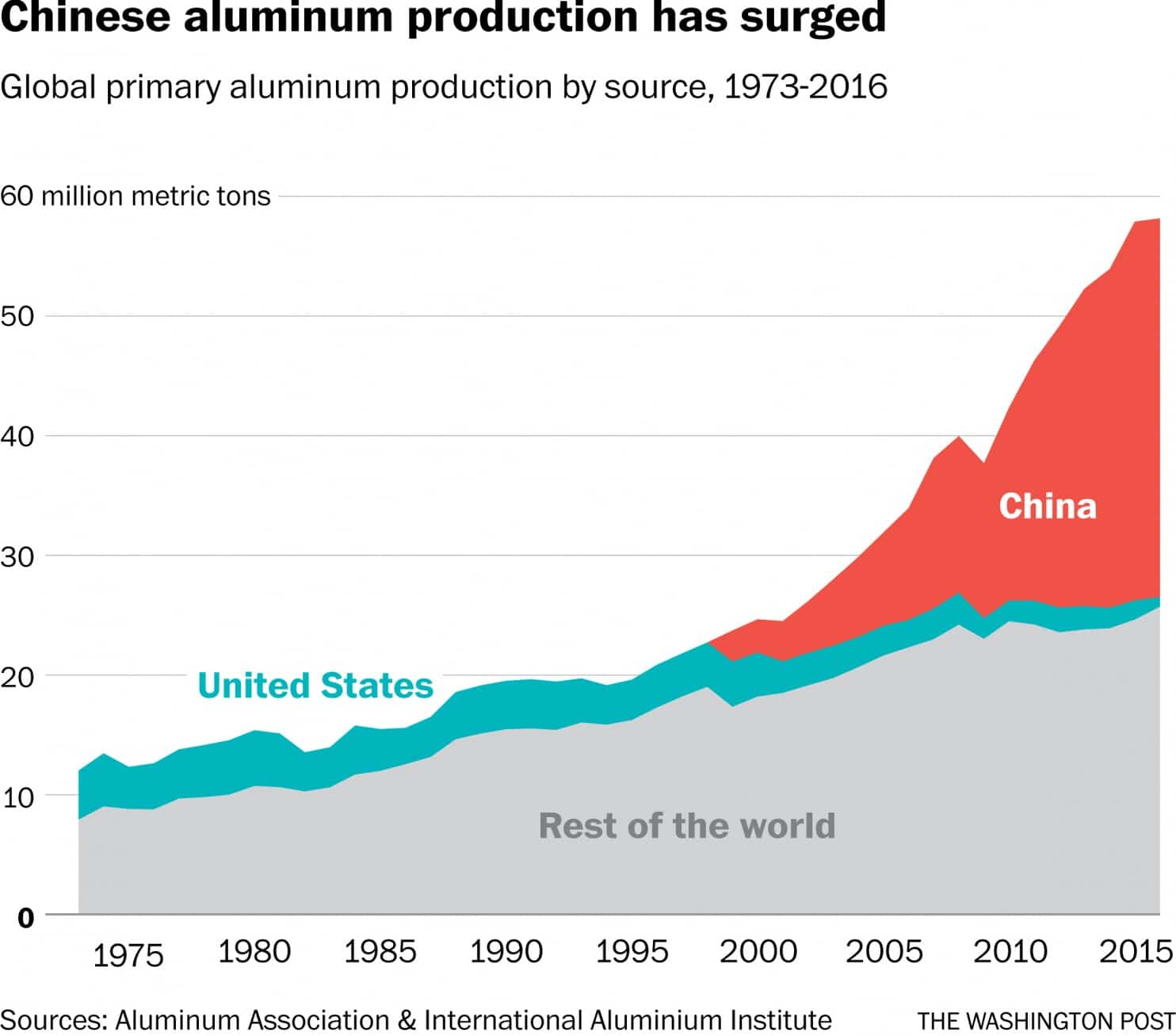

The debate over aluminum’s future in the United States comes after 20 years of China flooding the global market with the natural resource, depressing prices to a level where few U.S. companies can compete. The United States has gone from having 23 operational aluminum smelters in 1993 to just five today, with only two running at full capacity.

Over the last five years, Hawesville’s Century Aluminum has twice issued notices that it would shut down permanently in 60 days, before pulling its business back from the brink. It has laid off more than 300 people in just the last two years and has been scrapping unused machinery for extra cash. Another dip in global prices could shut its doors forever. The more than 200 jobs that remain, while they pay well for the area, are grueling ones, often 16 hours of physical labor in temperatures reaching 140 degrees.

If the administration’s investigation finds that the country’s defense capabilities are being compromised by the decline of aluminum plants like the one in Hawesville, the president would have the power to impose tariffs or other restrictions on imports. Because it’s in the name of national security, Trump could circumvent a longer, more complicated process for changing trade policy at the World Trade Organization.

President Trump signed a memo directing his administration to investigate the impact of aluminum imports on national security.

The Obama administration filed a complaint about China’s aluminum industry at the WTO in January, but it has yet to deliver a ruling. Instead, the Trump administration has relied on a rarely used trade measure known as a Section 232 probe. The administration has also announced such a probe into steel.

Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross called the kind of high-purity aluminum produced by the Hawesville smelter “a hugely important thing to defense.”

[clickToTweet tweet=”Our #industrial base is our most important, competitive #weapon in any kind of global conflict. ” quote=”“Our industrial base is our most important, competitive weapon in any kind of global conflict,” he said. “I’m not a warmonger, but the best way to be sure you have to fight a war is if everybody knows you are incapable of defending yourself.””]

Yet any resulting action could have unintended consequences. Past administrations have used Section 232 sparingly, because of the concern that this exception to international trade guidelines might become the new rule.

“If we can use national security to block aluminum imports, other countries can and will use it to block agriculture and aviation imports,” said Derek Scissors, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. “Widespread use of 232 by the United States won’t just curb imports, it will curb trade.”

Others question whether the investigation is really motivated by security concerns, or whether it is a veiled effort to protect U.S. companies from foreign competition.

Tom Leary, an analyst at the consulting firm Harbor Aluminum, said the United States has plenty of access to aluminum in Canada, a top ally from which the U.S. government already sources a lot of defense equipment.

Chinese producers don’t directly export raw aluminum into the United States, so tariffs may have little effect on the country that many in the aluminum industry say is the real culprit. Chinese aluminum production has hurt U.S. producers by flooding global market and depressing prices everywhere.

Chrystia Freeland, the foreign minister of Canada, said she had pressed Trump administration officials about the investigation’s potential effects. “It’s amazing and astonishing and absurd to me that Canada would be considered in that frame given our shared security interests,” she said in an interview.

If the Trump administration chooses to restrict aluminum imports, that could keep the doors open for Century, which operates mostly in the United States, but it would raise costs for other businesses — like the industries that mix the metal into alloys, roll it out into long sheets or stamp it into automobiles and window frames.

It could also mean higher costs for the ultimate buyer of American-made defense goods: the U.S. government, said Dan Stohr, a spokesman for the Aerospace Industries Association, a trade association for the defense industry.

The national security is a wrinkle in a larger debate over manufacturing in America: whether the government should intervene to shelter a place like Hawesville from the winds of global trade.

It’s a familiar topic here, where locals have been buffeted by forces beyond their control for decades. The Whirlpool factory moved its jobs to Mexico. A glut of Russian metal put the local steel mill out of business. Competition from China forced furniture factories to close.

Trump’s promises to punish companies that moved their operations abroad resonated here, with locals saying they just want a level playing field. Like his brother, Hughes voted for Trump. “I wanted to see some kind of different change. The previous eight years didn’t work out so well for us,” he said. “When you start seeing places close down, you start looking for an answer.”

The community still has jobs, but it shows signs of wear. In Cannelton, Ind., across the Ohio River, shop windows are boarded up.

At the Century plant, the jobs, already taxing, have become harder with cutbacks. Union members say that four employees now do the work that 10 once did. Overtime is common, with workers tending smoldering vats of molten metal for up to 16 hours a shift. Even though the factory is open to the breeze, the temperatures can climb to 140 degrees in the summer. Workers drink two or three gallons of water a day, and at the end of their shift, they can wring the sweat from their clothes.

Despite the grueling work, locals say these are good jobs that are worth protecting. Hughes and Young rely on them to raise four kids each. The average job at the Hawesville plant pays $23 an hour — $10 or more an hour than the jobs that their friends who have been laid off from the smelter have found in furniture factories, prisons, and lawn care services. The difference, locals say, is affording three-bedroom house vs. being stuck in a trailer.

Before coming to Century Aluminum, Hughes and Young used to work across the river in Indiana at an iron foundry and then at an aluminum smelter owned by Alcoa. Young was at the Alcoa plant in January 2016 on the day it announced that it was closing its doors, laying him off and hundreds of others. He counts himself lucky to have found a job at Hawesville — and frets about what its potential closure could mean.

“If you take this job away, you’re taking one of the best-paying jobs in this area,” Young said. “If we lose the smelting jobs around this area, it’s going to destroy this community.”

Yet the forces buffeting Hawesville won’t be entirely mitigated even if Trump announces tough action to protect aluminum. Locals say that, in addition to trade deals and the rise of China, part of the reason for job losses is the declining fortunes of coal, which is what brought the aluminum industry to Kentucky in the first place.

To produce aluminum, smelters run a powerful electrical current through the raw material, alumina. When it was running at full capacity, the Hawesville plant used nearly 500 megawatts (MW) per hour, comparable to a city the size of Austin or Columbus, Ohio.

Because the process is so energy-intensive, smelters tend to crop up in places with energy to spare — like the oil-rich Middle East or the geothermal hot spot of Iceland.

But in the United States, changes in the economy have made aluminum smelting less viable. In Washington state, for instance, the smelters that used to operate near the hydroelectric power plants along the Columbia River have been priced out by the power-chugging server farms of tech companies such as Microsoft.

As U.S. regulations on carbon-intensive coal electricity have gotten tougher, Hawesville’s rationale for aluminum began to fade.

Young hopes smelting jobs survive in the Hawesville area, but he’s preparing in case they don’t. He said he’s going to preach to his kids that education is the only way to succeed.

“I don’t want my kids to have to work the schedules I’ve had to work, the long hours I’ve had to work,” he said. “I want them to know that there’s more out there than just backbreaking labor.”

SOURCE: Washington Post

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!