NEW YORK CITY — Stephanie Wilson was reaching for a receipt inside a paper shopping bag from Saks Fifth Avenue when she found a letter pleading, “HELP HELP HELP.”

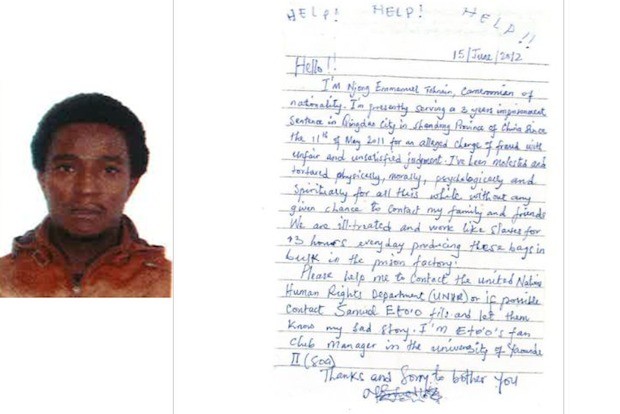

The note, which Wilson found after buying a pair of Hunter rain boots at Saks in September 2012, was signed Tohnain Emmanuel Njong and was accompanied by a small passport-photo sized color picture of a man in an orange jacket, she said.

The letter, which also included a Yahoo email address on the back, triggered a hunt for the whereabouts of the mystery man.

Wilson showed the missive to the Laogai Research Foundation, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group founded to fight human rights abuses in Chinese prisons. The nonprofit foundation began investigating using its contacts on the ground as well as online, a representative confirmed to DNAinfo New York.

But when Njong’s Yahoo email address bounced back, the nonprofit was unable to locate him.

Harry Wu, the founder of Laogai Research Foundation, spent 19 years in a Chinese prison factory, known as laogai. He said he took steps to verify the letter and believes that Njong took a huge risk in writing and sending it.

“There would be solitary confinement until you confess and maybe later they increase your sentence — or even death,” Wu said.

His organization referred the letter to the Department of Homeland Security, which investigates allegations of American companies using forced labor to make their products.

Homeland Security officials confirmed to DNAinfo that they were made aware of the letter, but could not say if they investigated it or are currently looking at Saks in connection to it. They also could not discuss Wilson’s claim that DHS agents interviewed her in June 2013.

But a DHS official said it’s not the first report of a cry for help letter from China ending up on American shores.

According to DHS senior policy adviser Kenneth Kennedy, the department was made aware of a woman in Oregon who made international news in 2012 when she discovered a similar letter detailing abuse and grueling labor in a Chinese prison when it fell from a Halloween decoration she’d bought at Kmart.

The Oregon letter was anonymous, though The New York Times later tracked down the man who said he wrote it.

A representative for Saks Fifth Avenue confirmed that the store was notified of the letter by the Laogai Research Foundation in December 2013 and said the company took the allegation seriously and launched an investigation, according to Tiffany Bourre, spokeswoman for Hudson’s Bay Company, which took a controlling stake in the famous department store last December.

Bourre said Saks does have its paper shopping bags made in China, but the company was unable to determine the specific origin of the bag that contained Njong’s letter and photo.

Hudson’s Bay Company is currently in the process of ensuring all vendors meet the new company’s standards on workers’ rights, Bourre added.

“HBC has a rigorous social compliance program that outlines our zero tolerance policy, which includes forced labor,” she said.

Two U.S. laws make it illegal for products made using slave, convict or indentured labor to be imported into the United States, according to Kennedy. However investigations are difficult with DHS required to prove how much a company knew about its own supply chain.

“Was there actual knowledge [of slave, convict or indentured labor?] Or was there knowledge that they avoided knowing or seeing?” Kennedy said. “All that plays into the investigation.”

A legal clause known as the consumptive demand exemption, which Kennedy referred to as “the Achilles heel of these laws,” can also greenlight imports regardless of the type of labor used if domestic consumption cannot be met otherwise.

In recent weeks, using the now-inactive email address and social media accounts, DNAinfo located a man who said he wrote the letter that Wilson found.

In a two-hour phone interview, a man who identified himself as Njong said he wrote the letter during his three-year prison sentence in the eastern city of Qingdao, Shandong Province.

Unprompted, Njong described obscure details in the letter, like its mention of Samuel Eto’o, a professional soccer player on English premiere league team Chelsea, who like Njong is from Cameroon in West Africa.

He added that he wrote a total of five letters while he was behind bars — some in French that he hid in bags labeled with French words, and others in English, he said.

Njong, who is now 34, said he had been teaching English in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen when he was arrested in May 2011 and charged with fraud, a crime he said he never committed.

He said he was held in a detention center for 10 months while awaiting a government-sponsored lawyer, who represented him at his court trial and sentencing. He said he was barred from contact with the outside community.

Njong’s arrest and imprisonment were confirmed by his legal aid lawyer in China, whose name DNAinfo is withholding for the lawyer’s protection.

Embassies for Cameroon in Beijing and Washington did not return emails or calls for comment. The Chinese embassy in New York did not respond to requests for comment.

Njong said he was imprisoned in the eastern city of Qingdao, Shandong Province, where he was forced to work long days in a factory, starting at 6 a.m. and continuing as late as 10 p.m. He sometimes made paper shopping bags like the one from Saks, while other times he assembled electronics or sewed garments.

Each prisoner was required to meet a daily production quota, Njong said. He said he and the other convicts were given a pen and paper to record their productivity — and that he used that pen and paper to secretly write his letters.

“We were being monitored all the time,” Njong said. “I got under my bed cover and I wrote it so nobody could see that I was writing anything.”

He said he hoped the letter would help lead someone to him.

“Maybe this bag could go somewhere and they find this letter and they can let my family k

now or anybody [know] that I am in prison,” explained Njong.

Njong said he was discharged from prison in December 2013 — he received a reduced sentence for good behavior — and was put on a plane back to Cameroon, where he reunited with relatives who had no idea what had happened to him and had believed him to be dead, he said.

After struggling to find work in his home country, Njong recently moved to Dubai and secured a job that will allow him to stay there.

He said that though his imprisonment ran its course without intervention, he was happy that his letter made its way into at least one person’s hands.

“It was the biggest surprise of my life,” said Njong. “I am just happy that someone heard my cry.”

Wilson, who has never spoken to Njong, said she thinks about his plea for help all the time. She had always been mindful of the products she purchased and where they were made in a bid to avoid sweatshop labor, but she never thought to worry about generic products like shopping bags.

Wilson has worked for the nonprofit Social Accountability International for the last four years.

“This has been the biggest eye-opener for me,” Wilson said. “I have never once thought about the people making my shopping bag or other consumable products like the packaging of the food I buy, or the pen I write with or the plastic fork I eat my lunch with.”

e”/>

e”/>