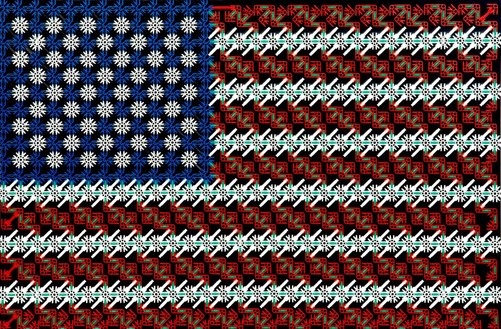

94 Percent Of American Flags Imported Into The U.S. Last Year Came From China

Millions of Americans showed their patriotism on the 4th of July by waving a product that may have come from China.

Ninety-four percent or $3.6 million worth of the flags imported into the U.S. last…

Eight-Story Building Collapses in Bangladesh: Who Really Pays For Our Cheap Clothes?

Eight-story building collapses in Bangladesh

Anna McMullenSpecial for CNN (CNN) -- The sad fact behind the building collapse in Bangladesh in which hundreds died is that it isn't an isolated problem. The story will…

Is the U.S. Manufacturing Renaissance Real?

A worker welding the outside of a safe at the Champion Safe Co. manufacturing facility in Provo, Utah, on Wednesday, Feb. 22, 2012. - GEORGE FREY / BLOOMBERG / GETTY IMAGES

Rana Foroohar and Bill Saporito

U.S. manufacturing…

Walmart to Boost Sourcing of US Made Products: Hiring 100k Veterans

Walmart announced bold commitments to increase domestic sourcing of the products it sells and help veterans find jobs when they come off active duty. Speaking at the National Retail Federation’s annual BIG Show, Walmart U.S. President…

Walmart to Boost US-Made Products

Walmart today announced bold commitments to increase domestic sourcing of the products it sells and help veterans find jobs when they come off active duty. Speaking at the National Retail Federation’s annual BIG Show, Walmart…

President Obama Touring K’NEX Manufacturing Facility at The Rodon Group

When President Obama comes to Montgomery County on Friday, he will speak in front of a two-foot-tall toy helicopter, a toy roller coaster, a toy grandfather clock, a motorized toy carousel, and an American flag made of 49,000 K'Nex pieces.

The…

Manufacturing Jobs Aren’t Coming Back, No Matter Who’s President

The percentage of Americans working in manufacturing fell under President Reagan. It also fell under Presidents Bush, Clinton, Bush and Obama (respectively).

Which is to say,…

Made in America, Again: Why Manufacturing Will Return to the USA

For over a decade, deciding where to build a manufacturing plant to supply the world was simple for many companies. China was the clear choice with its seemingly limitless supply of low-cost labor, an enormous, rapidly developing domestic market,…

Outsourcing May Cause High Unemployment and Manufacturing Decline

All American Clothing Co., proud corporate members of The Made in America Movement, announces a new warning label that raises awareness of the consequences of outsourcing and buying foreign-made items in the United States.

May the following…

Made in USA… Again: U.S. Manufacturing Gains Momentum

Maybe the once-ubiquitous label, Made in USA should be updated to: Made in USA — Again.

According to a survey by my firm, Boston Consulting Group, 37 percent of U.S.-based manufacturing executives at companies with sales greater than…