What Is ‘Made in America’ Worth?

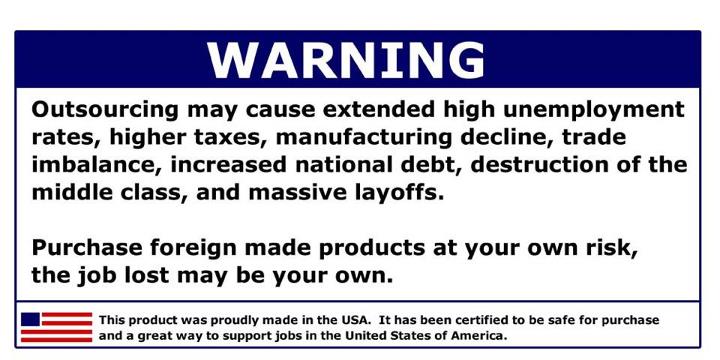

in American Made, Domestic Sourcing, Economy, Made in USA, Manufacturing & Sourcing/by The Made in America Movement TeamOutsourcing May Cause High Unemployment and Manufacturing Decline

in American Made, Domestic Sourcing, Made in USA, Manufacturing, Outsourcing/by MAM TeamAll American Clothing Co., proud corporate members of The Made in America Movement, announces a new warning label that raises awareness of the consequences of outsourcing and buying foreign-made items in the United States. Read more

Ann Arbor Firm Constructing Homes with Products Made in America

in American Made/by MAM Team

As Ann Arbor Builders Inc. hops aboard the slow train to economic recovery, the company wants to bring along other American businesses.

The Return of 'Made in America'

in American Made, Sustainability/by MAM Team4/11/2012 | Written By Anthony Mirhaydari, MSN Money

Clearly, something’s still wrong with the economy. By the metrics that matter to most people, the Great Recession has not ended. Employment, retail sales, industrial production, home prices, most of the stock market and real incomes are all below their 2007 peaks. Food stamp usage is at a record high and rising.

But something’s going right, too. And I want to focus on that this week.

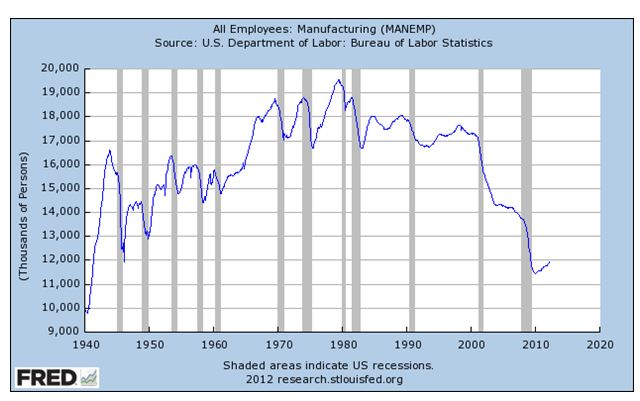

American competitiveness is back, albeit largely because of the pain we’ve endured. Our dollars are worth less, and real wages are lower. Corporations are responding, with new factories springing up and manufacturing jobs blooming like flowers welcoming the spring. Overall, the U.S. has added nearly 500,000 manufacturing jobs since the beginning of 2010 — the first period of significant growth since the late 1990s.

Experts say these trends are likely to continue.

Bank of America Merrill Lynch researcher John Inch wrote in a recent note to clients that the “U.S. economy is in the early stages of a long-term manufacturing renaissance.” Analysts at the Boston Consulting Group add that rising wages and other forces have steadily eroded China’s “once-overwhelming cost advantage as an export platform for North America.”

Thanks to higher U.S. worker productivity, as well as supply chain, cheap energy (natural gas) and logistical advantages, the BCG team says that by around 2015 “it may start to be more economical to manufacture many good in the U.S.”

In short, we could be on the cusp of revival of “Made in America,” with workers paid good wages for building things again. And for the millions in the army of the unemployed, it can’t come soon enough.

Silver lining to storm clouds?Don’t get me wrong. Our problems still run deep, and I’m not saying happy days are here again; I’m merely pointing out one of the few silver linings to be found.

We’ve long been too reliant on credit to supplement stagnant wages — and that’s left the West with an $8 trillion debt hole, according to Credit Suisse calculations. This fueled two bubbles and a financial crisis, and it resulted in the pitiful “recovery” we’re in now.

And so far, if the economy is reviving, most workers aren’t sharing in it. Real, inflation-adjusted wages have fallen in three of the past four months. This has never happened outside recession before. So it’s very possible we’re following Europe into the depths of a new downturn.

Last September, I argued that “the real recession never ended” and that, in reality, it started a decade or more ago as labor participation peaked in the late 1990s. We’ve been sliding lower ever since, trying to compensate for a lack of high-quality jobs and stagnant pay, with voodoo stimulus efforts out of Washington and an extreme, inflation-igniting easy-money policy from the Federal Reserve.

The core problem has been a hollowing-out of America’s manufacturing base because of increased globalization, the manipulative trade policies of China and others, and rapid technological change.

Washington, of course, hasn’t done anything about trade or jobs (except talk, of course). But the U.S. economy may find a way out of the hole anyway.

The depth of the problemBefore moving on, it’s worth remembering that something similar has happened before.

In many respects, the current situation resembles the Gilded Age of the late 1800s and the Long Depression, a global downturn that lasted from the 1870s through the 1890s. Replace the robber barons with hedge-fund managers and multinational CEOs, and the agitation over the Free Silver Movement with the Tea Party and the debate over the Federal Reserve’s stimulus efforts, and the similarities are striking.

The downturn was preceded by a period of global economic integration as steam power, the telegraph and railroads made the world smaller. Workers lost jobs to technology and foreign competition. The banking system was rocked by the panics of 1873, 1884 and 1893, driven by real-estate bubbles and stock speculation.

Our current role was played by the United Kingdom, an aging sovereign struggling to maintain its role as the world’s superpower. The role of the upstart United States is now played by vigorous up-and-comers like China and India. Check out this excerpt from A.E. Musson’s “The Great Depression in Britain, 1873-1896: A Reappraisal“:

“Britain was losing her technological lead; she was failing to modernize her plant, to develop new processes, or to modify her industrial structure with the same rapidity as Germany and the United States — owing to conservatism, the heavy cost of replacing old plant, and deficiencies in technical education.”

In other words, the British got lazy, making them vulnerable. We have the same problem now, and I outlined in “Are American workers getting lazy?”

The other part of today’s problem is that America’s free-trade policies put U.S. workers at a disadvantage, because trade partners aren’t playing fair. Beijing actively manages its currency’s exchange rate — accumulating trillions of dollars in reserves in the process — in an effort to ensure the country’s export-oriented growth isn’t threatened.

In this environment, research by the National Bureau of Economic Research shows that our economy will suffer if we don’t erect defensive trade barriers and tariffs.

Musson wrote that there was little doubt that a stagnation of British exports was “one of the most critical aspects” of the downturn and that aggression by trade partners was a primary cause. It’s the same for the United States today.

He writes: “Foreign trusts also adopted a vigorous policy of ‘pushing’ their goods abroad . . . while foreign industry and trade were greatly assisted by protective tariffs, export bounties, ‘drawbacks,’ and special low rates of rail transport. British business, on the other hand, had no such fiscal protection and assistance in this Free Trade era.”The result was a rise in calls for reciprocity and “fair trade.” It was argued that for Britain, as for the United States now, it would be ruinous to remain an open market when competitors were strongly protectionist. The result was a swing toward protectionism. Nothing much has been done on this front yet, but both presumptive GOP presidential candidate Mitt Romney and President Barack Obama have criticized China’s trade policies.

The tide is turningUnless the people rise up and demand change, I don’t believe the White House and Congress will do anything about our trade policies. Free trade and labor arbitrage have been very good for big business, pushing corporate profits

to record highs while average Americans struggle to fill their cars with gasoline.

Well-paid lobbyists will ensure that any anti-trade, anti-China legislation is dead on arrival to Congress. (Romney has promised to label China a currency manipulator, setting the stage for countervailing duties on Chinese goods. But legislation to do the same thing, which passed the Democratic-controlled Senate, has stalled in the Republican-controlled House.)

Fortunately, years of pain for American workers are bringing about a respite despite Washington’s recalcitrance.

The wage differentialConsider this: Back in 2000, in the twilight of the tech boom, factory wages in China averaged just 52 cents an hour — a mere 3% of what the average U.S. factory worker earned. In the years since, Chinese wages and benefits have jumped by double digits annually, with an average increase of 19% from 2005 to 2010.

With China’s workforce now peaking and labor shortages already developing in some of the coastal provinces, labor disputes and strikes — like the kind seen recently at factories supplying products as varied as flat-panel displays, auto parts and women’s lingerie — will surely become more common.

Beijing, mindful of the need to reorient China’s economy toward domestic consumption in the interests of sustainable growth, is becoming increasingly supportive of worker rights. Witness the recent regulatory spat over working conditions at Foxconn, the main supplier for Apple. Because of this, BCG anticipates further wage increases of 18% per year through 2015. By then, average pay in the Yangtze River Delta, the beating heart of China’s high-tech export machine, is expected to reach $6.31 per hour.

Here at home, fully loaded costs of U.S. production rose by less than 4% annually from 2005 to 2010 as labor unions became more flexible. Factoring in higher U.S. labor productivity, those Yangtze River Delta wages are likely to exceed 60% of U.S. manufacturing labor costs. After also factoring in favorable tax treatments for new factories, especially in Southern, nonunion U.S. states, the gap will be even smaller.

Plus, one must consider shipping expense, added wait times, and the plethora of hidden risks and costs of operating an extended global supply gain. China’s cost advantage won’t add up anymore.

Nor are other low-cost places like Vietnam and Indonesia suitable replacements, since they lack the infrastructure, talent, supply networks and productivity that have made China so attractive. For many, returning to the land of Stars and Stripes will be the best choice.

The impact on the economy will be “significant,” according to the BCG team. It identified seven industry groups — responsible for $200 billion in imports from China annually — for which rising costs in China will likely prompt the return of “Made in USA.” Examples include furniture, appliances, fabricated metals, machinery, transportation equipment, and plastics and rubber goods. Production of other items, such as apparel, textiles, footwear and computers, is expected to remain offshore.

What will this mean? Take a look at the chart below, showing an uptick in manufacturing jobs after a long decline.

Examples abound, though many of the companies are relatively small.

ET Water Systems, which had made irrigation controls in Dalian, China since 2002, has moved production and assembly to San Jose, Calif. High-end cookware maker All-Clad Metalcrafters is bringing lid production back to the U.S. from China. AmFor Electronics now enjoys lower delivery times and ease of design change after relocating wire-harness production from China and Mexico to Portland, Ore.

While we have a long road to travel to get back to where we were, at least we’re moving in the right direction. Things could be accelerated by focusing on America’s dilapidated infrastructure, encouraging domestic investment in new productive capital with permanent tax credits, reforming health care and education to increase productivity and lower benefit costs, and fingering China for what it is: a blatant mercantilist.

At the time of publication, Anthony Mirhaydari did not own or control shares of any company mentioned in this column in his personal portfolio.

Which Logo Would You Choose for The Made in America Movement?

in American Made/by MAM TeamWe loved all the sample designs, but could not decide on one.

So we are asking you, our loyal followers!We have created two (2) polls so that you may choose your favorite!

We have our favorites!!! Let’s hear what yours are!

Thank you for all your help, our loyal constituency!!!

Thank you, SantiDesign, for coming to our rescue!

Check out their work. They are amazing at their craft.

—

Polls close Friday, April 13th at midnight. (Yes, folks, Friday the 13th.)

Poll results will be announced Saturday, April 14th in the afternoon.

Made in USA Making a Comeback – Furniture Company’s Revival Has Global Message

in American Made, Reshoring/by MAM Team“To do something like this HAS to be a business decision,” he says, “but it is emotional and it is sentimental to be able to come back and make something again and to impact people in such a positive way.”

What happens in the cavernous factory on Cochrane Road could bring economic security to workers in a state that, by one estimate, has hemorrhaged tens of thousands of jobs to China in the last decade.

But what happens here could also offer larger lessons about U.S. workers in a global market, the appetite for American-made goods and the future of an industry decimated by foreign competition.

___

Bruce Cochrane was in China, 8,000 miles away, when he first began thinking about reviving the family’s business three years ago.

Over a decade of consulting, he’d witnessed dramatic changes in China’s economy. Manufacturing workers’ wages — 58 cents an hour, on average, in 2001 — were approaching $3. The once abundant labor supply was drying up. Shipping costs were higher because of rising fuel costs. Quality was suffering because of high turnover. It could take three or more months to get a piece of furniture after it was ordered — compared with 30 days or less in the U.S. The clear-cut advantages of manufacturing in China were disappearing.

That same point was made in a 2011 report by The Boston Consulting Group that estimated that “reshoring” by companies could result in 2 to 3 million new jobs. About a quarter would be directly in manufacturing, and the rest would work for suppliers or service industries.

Furniture, the report said, is among the seven areas where this is most likely to occur. The costs of shipping bulky products and the ample supply of wood in the U.S. make it a prime candidate for domestic manufacturing; China has to import wood.

“The pendulum is swinging,” says Hal Sirkin, the report’s lead author. He says wages are rising 15-to-20 percent a year in China and U.S. workers are, on average, more than three times as productive

The report predicts that by 2015, these industries will likely reach a “tipping point” where the cost advantages of China will have shrunk to a point where U.S. companies may see it’s to their benefit to return production or set up a new base here.

“It’s still early,” Sirkin says. “We don’t know all this is going to happen, but companies are starting because the economics are starting to look favorable. I was surprised to see it happening as quickly as it is.”

It is happening at a time when Americans — historically proud of the nation’s manufacturing might — are showing frustration with the migration of those jobs to China and elsewhere. An ABC News/Washington Post poll in February found that nearly 75 percent of those surveyed favor raising taxes on businesses that move manufacturing jobs overseas.

In January, President Barack Obama hosted a White House forum on in-sourcing, featuring small and large companies that have invested in the U.S. And in his State of the Union speech, Obama called for an economy “built on American manufacturing.” He said the resurgence of the U.S. auto industry “should give us confidence.”

A March trade group survey found expansion in 15 of 18 manufacturing industries, including autos, steel and furniture.

The president’s Republican rivals, meanwhile, also have touted the value of manufacturing and talked tough about China. Mitt Romney has vowed to declare China a “currency manipulator” and impose tariff penalties. Rick Santorum, who has emphasized his blue-collar roots, proclaimed he wants to “got to war with China” to create the best business climate for America.

But predictions about a rebirth of manufacturing and muscular rhetoric about resolving trade imbalances are met with understandable skepticism.

Consider the numbers: More than 5.5 million manufacturing jobs were lost from 2000 to 2011, though there has been a modest recovery in recent years, There are economists who say some jobs are gone forever because of productivity and robotic gains. And U.S. multinationals eliminated more than 800,000 jobs in the U.S. while adding 2.9 million overseas from 2000 to 2009, according to federal figures.

The trade deficit with China — $295 billion last year — has cost nearly 2.8 million U.S. jobs from 2001 to 2010 and almost 70 percent have been in manufacturing, according to a 2011 report by the Economic Policy Institute.

The report’s author, Robert Scott, found that about a third of all displaced jobs were in the computer and electronic parts industry; other areas include textiles, apparel and furniture. North Carolina’s loss of nearly 108,000 jobs ranked it among the top 10 hardest-hit states.

Reshoring “is not only a drop in the bucket … it’s not making a dent in the growth of the trade deficit,” says Scott. “It’s a classic example of counting trees instead of focusing on the forest. You may see a few trees popping up but the forest is still falling down.”

___

Bruce Cochrane started learning the furniture trade as a teen. He worked with his father, Theo — also known as Sonny — who ran the company with his brother, Jerry

“He always instilled in me that it was OK to take chances,” Cochrane says. “He’d always say, ‘If you aren’t fishing, you aren’t catching anything.'”

Cochrane remembered those words when trying to decide whether to take the plunge. “I actually had a dream of him telling me that and he was in his fishing gear. At that point, I said, ‘Yep, I’m going to do it.'”

That decision came more than a decade after the Cochranes got out of the business. In 1997, the family sold the company to another U.S. manufacturer; the factory remained open and the workers continued to make furniture with the Cochrane name. Over the years, though, more and more work was done in China. The plant finally closed in late 2008, the building was sold and the equipment auctioned off.

Cochrane carefully developed a business plan, and by 2011, he was ready — thanks, in part, to financing from a local bank. The president turned out to be a former company worker.

Last spring, Cochrane — who has two partners — walked into the empty 300,000 square-foot factory.

He soon added family touches, among them an oil painting of his father, hung on the lobby wall. With their silver hair and Clark Kent glasses, father and son share an uncanny resemblance. His eyes mist when he mentions him. “I think about how much he would love this,” he says.

Starting over, Cochrane also looked to the past, recruiting former company workers.

When he phoned the first two — both weren’t working — he heard doubt in their voices.

“Both of them said, ‘I don’t think I can do that anymore,'” he recalls. “They had lost their confidence. It (joblessness) puts people in such despair. They think there’s something wrong with them rather than the circumstances.”

Karen Padgett was one of those first calls. She’d worked her way up from the shipping department to human resources manager, spending 35 years with Cochrane and its successor. When the factory closed, Padgett was adrift.

She was in her 50s, jobs were scarce and a lifetime of working with folks who’d become good friends was suddenly gone.

“It was such a loss,” she says. “If you have a death in the family, you feel like you just can’t pick up and go forward. That’s how I felt. … I knew I needed to work. I knew I was still vital enough to do something, but I didn’t know what I would do.”

Jerry Cochrane had urged her to return to school, so she enrolled in a nearby college to polish her skills.

She was just starting to scope out job prospects when Cochrane called. She knew immediately she wanted the job, but had a moment of hesitation. “Being out of work strips you of your confidence,” she says. “I felt, ‘Oh, gosh can I do this?’ I just needed somebody to reassure me.”

Cochrane described his plans to build American-made furniture. “He said, ‘I really believe it’s coming back and we can make some money doing this and we’ll have a good time, I promise.'”

Padgett is now on the other end of the job search, fielding calls and conducting interviews. She’s received about 1,400 applications for what eventually will be about 130 jobs. (Starting salaries range from $9 to $16 an hour.)

One caller had a particularly poignant story: He said he wanted to work for the company because as a boy, he’d lived down the road from the old Cochrane factory. His single mother had struggled to provide for her six kids, he said, and when times got tough, Sonny Cochrane made sure their utility bills were paid.

The man was eventually hired.

About two-thirds of Lincolnton workers have experience in the furniture industry. North Carolina lost nearly 60 percent of its furniture jobs from 1999 to 2010, as the percentage of imported furniture sold in the U.S. doubled.

It has been a slow-motion economic disaster. Padgett says everyone noticed how one factory, then another closed, and yet “it was like we just woke up and it was swept out from under us. It kind of slapped us in the face when it was all gone.”

It was so traumatic that when Cochrane asked Pat Hendrick to return as purchasing manager, she was thrilled but had one question: “‘Will you be importing anything?’ I didn’t want to be involved with anything like that,” she says, “because that’s how I lost my job.”

To Hendrick, her job offer was an answered prayer. Literally. Every day while she was unemployed, she says, she’d pray she’d find work. One day, she tried something a little different:

“I said, ‘God, I’m tired. You’re going to have to drop a job in my lap that you know I can do and have people there that I can get along with and work with. I’m just leaving it in your hands.'”

Cochrane called at 8:59 a.m. the next day.

Driving back into the parking lot for the first time, Hendrick says she felt as if she’d never left. But two years of unemployment aren’t easily forgotten.

“After losing your job of 32 years,” she says, “you do have reservations. I’m comfortable here, but I don’t think I’ll ever have that same sense of security that I thought I had.”

Dean Hoyle understands uncertainty. After nearly 30 years at the factory, he found himself out of work, too, scraping by doing yard work and mowing lawns.

His situation, he says, was even more agonizing because he was still recovering from the death of his wife from breast cancer, and work, he says, “had been a rock to me.” After 14 months, Hoyle was hired at another furniture company, only to be laid off last year.

Hoyle, who works in the packing department, is struck by how much has changed since he first walked into the factory as a fresh-faced Army veteran. “These places were all up and running when I got out of school,” he says. “Where are all the people going to go now and what are they going to do? Not everybody can be a computer programmer.”

Hoyle’s ruddy, mustachioed face breaks into a wide smile as he recalls going to the bank to deposit his first paycheck from the new job.

“I’m 57 years old and soon to be 58, and I’ve got enough sense to know this area is not full of opportunities for someone like me,” he says. “If I could sum it up in one word, it would be grateful.”

___

In January, Lincolnton’s first piece of furniture — a cherry-wood nightstand — came off the line. All the workers signed it.

That same month, Bruce Cochrane had two dates in Washington, D.C. The first was the White House conference on insourcing, where he met Obama. The other was an invitation to sit in the first lady’s box at the State of the Union speech, where the president spoke of a manufacturing renaissance. (For the record, Cochrane says he’s never voted for a Democratic president.)

Cochrane thinks there’s an appetite for U.S.-produced goods. He attaches a “Made in America” tag to each piece of his company’s furniture, with a message: “We take immeasurable pride in the fact that our furnishings are made of select solid American hardwoods,” he wrote, appending his name.

“I think people realize that made in America means jobs in America,” Cochrane says. “And they have experience with a loved one or a family member or a friend who lost a job so it becomes more and more personal to them.”

Bud Boyles, owner of the Carolina Furniture Mart in Lincolnton (where the nightstand is displayed), senses a similar mood.

“Timing is everything and he’s definitely got the timing right now,” Boyles says. “It might be a hard first year for him but people are saying, ‘We’re going to have to take a look at what we’re doing. We have to go back to our roots and help our neighbors.””

There have been small moments of satisfaction these first months, such as touring the factory with a friend, who said he thought he’d never again smell that earthy scent of fresh-cut wood. “It’s nostalgic,” Cochrane says.

But there have been problems, too. A malfunctioning machine needed fixing and the plant had to be rewired, a costly project. The technology has become so efficient that Cochrane says he’ll need half the workers he first expected — though of course that’s a mixed blessing, given the area’s struggle with unemployment.

Within thre

e years, Cochrane hopes to do $25 million in business a year. For now, he’s determined to prove the naysayers wrong.

“People in this industry still don’t believe this can be done,” he says. “I don’t have any doubt at all.”

___

by THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Sharon Cohen is a national writer for The Associated Press, based in Chicago. She can be reached at features@ap.org

Made in USA – All American Clothing Company Keeps True to Its Name

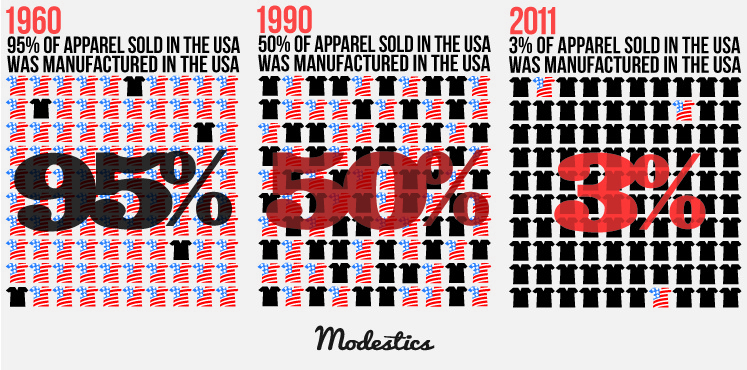

in American Made, Products/by MAM TeamIn an age where approximately 98 percent of all clothing worn by Americans is produced overseas, Nickol’s company is a true rarity. Furthermore, his ideas about how to run a clothing manufacturing company are a far cry from modern industry standards. No pep talks about profit and productivity here. Nickol’s company mantra is: “Creativity, implementation and progress.”

Inspired by a shocking discovery

Nickol co-founded the American Clothing Company with his son, B.J., in 2003. Prior to this venture, Nickol was employed by another blue jean manufacturer, who he declined to name. After decades of working as a salesman of American-made jeans, Nickol discovered that the company he had worked for had begun outsourcing its production to another country. That hallmark of American identity, the beloved blue jean, was now being made in Mexico.

“It’s about people and the enjoyment of a standard of living. We eat well and we know our job [is] going to be there tomorrow,” Nickol said.

Nickol predicts that he could be making 25 to 50 percent more profit if he were to outsource clothing production to Mexico or some other country. But outsourcing is not an option for his company, whose clientele appreciates the patriotism and ingenuity that the All American Clothing Company represents. Many of All American’s customers are veterans over the age of 50, a demographic that is nostalgic for the more self-sufficient America of decades past and wary of the outsourcing of so much American industry. His customers are as concerned with buying from a company whose emphasis lies not only in providing its customers with quality products but in caring for its employees.

Investing in America

Nickol said he wishes other companies would follow his lead and move production back to the United States. He added that he wouldn’t even mind the competition.

“We’re all here to help each other get through this,” he said.”I have a passion for the U.S., and I am so terribly sick of the situation we have right now, and what happens to honest, hard-working people.”

According to a recent study by the nonpartisan think tank Economic Policy Institute, the outsourcing of manufacturing and other jobs to China alone has cost the United States approximately 2.8 million jobs in the past decade. Many of these jobs come from within the apparel industry

Nickol said he considers this dependence on foreign labor to be unhealthy for the U.S. economy for many reasons, including the destruction of an income tax base to provide funding for public schools and other necessary services. He said his goal is to help restore health to the American economy through his role as an innovator in the apparel industry. To this end, he is often reminding himself and his employees that the time to fix the U.S.’s broken economy is now.

While others measure their progress in dollars, he tends to think of progress in terms of how well he can accomplish his goals. His advice to other entrepreneurs considering trying to change the way American businesses run: “Don’t let things happen to you,” he said. “Go make something happen.”

#POTUS Gets Made in Maine New Balance Sneakers

in American Made, Products/by MAM TeamSOUTH PORTLAND, Maine — U.S. Rep. Mike Michaud used President Barack Obama’s visit to the state on Friday to try to give a boost to what’s left of its shoe industry, urging the commander-in-chief to insist that the Department of Defense provide U.S.-made sneakers to new recruits.Michaud, D-Maine, had a special pair of New Balance sneakers made for the president, underscoring the company’s continued production in Maine, where it employs 900 workers.”The Department of Defense is circumventing the Berry Amendment that requires the military to be attired head to toe in American-made clothing,” Michaud said Friday, adding that U.S.-made sneakers would be consistent with Obama’s goal of bolstering domestic manufacturing.

“Let’s take the money that we’re no longer spending on the war,” he said. “Let’s use half of it to pay down our national debt and the other half to do some nation-building here at home.”

The back-to-back events featured some of the best of Maine, with lobster corndogs, lobster rolls, oysters, smoked salmon and beef, all produced in the state.

The sneakers, with “President Obama” sewn on the heels, also were made in Maine by New Balance, part of a dwindling number of shoe brands that carry the “Made in the USA” label.

Nationwide, the number of shoe-manufacturing jobs has dropped from more than 200,000 in the 1970s to about 12,500, according to the U.S. Department of Labor. In Maine, well-known Maine brands such as G.H. Bass, Cole Haan, Sebago and Dexter have shuttered factories and moved production out of the country.

New Balance, which has three factories in Maine and two in Massachusetts, plus others overseas, is the last major athletic shoe manufacturer in the U.S., company spokesman Matt LeBretton said.

The Department of Defense circumvents the Berry Amendment by giving new recruits allowances so they can buy their own shoes for athletic training, Michaud said. The shoes used for physical training should be put out to bid just like military boots, he said.

The Obama administration declined to comment. But Obama did mention manufacturing in his speech, saying he wants the next generation of manufacturing “to take place right here in Maine.”

New Balance contends that there are several other U.S. companies that would be interested if the Department of Defense chose to put the athletic shoes out to bid.

“It’s the right thing to do,” said LeBretton, the company spokesman. “We’re asking the Defense Department to follow the law. We’re not asking for special treatment or an earmark for our company. We’re just asking them to follow the law on the books.”

Buy Made in USA Products – Yes, it Matters

in American Made/by MAM TeamAnswer: Most individual items DO have Made in USA available; Avoid big box stores, search online, and contact the manufacturer if you are not sure.

“But Made in USA products are too expensive.”

Answer: Not true. While the initial cost may be more (in some cases), over the life of the product it is actually less expensive due to repair and/or replacement costs. It is cheaper to buy quality than quantity. Don’t you remember your parents and grandparents fixing things rather than buying new replacements?

Some Facts:

- Every time you buy a foreign product you are sending a large portion of that money into foreign hands; money that used to stay here and provide good paying jobs and tax revenue for your Local, State, and Federal government. China’s economy is booming while we are in recession.

- Every time you buy a foreign product you are giving the corporation more reason to continue the outsourcing trend

- Every time you buy a foreign product you are eliminating a U.S. job. This job could be your relative or neighbors.

- Every time you buy a foreign product you are lowering your wage. It gives companies and opportunistic politicians the opportunity to call for “streamlining” “lower wages” “lower health-care benefits” “lower taxes for the rich” “lower Social Security” “lower government/the peoples services”

- Every time you buy a foreign product you are probably purchasing an inferior/cheap product that will most likely fail making it a waste of money. You may have to replace the product several times making it more expensive than the American made equivalent.

- Every time you buy a foreign product you could be putting yourself and your children at risk by exposure to lead, cadmium, and other toxic materials. Foreign products DO NOT get tested nor is there any consumer protections for these products.

- Every time you buy a foreign product you are destroying the middle class and their/your neighborhoods. The loss of wages and ultimately their homes provides a decrease in tax revenue and invites rich slumlords to take over once working class areas turning them into neglected slums. Local services such as snow plowing and street paving decline and taxes go up.

- Every time you buy a foreign product you are helping the rich get richer. Fact is that while the ranks of the middle class dwindle, the rich are gaining complete influence and controlling the direction of Federal and State governments. We have no say when these people are in control. We are losing our voice. Money is #1 to certain individuals/entities. Re-gain control and reverse the trend by using your purchasing power and buy/demand products Made in USA!!!

Courtesy of MadeinUSA

INQUIRIES

Media: PR Department

Partnership: Marketing

Information: Customer Service

The Return of ‘Made in America’

The Return of ‘Made in America’