How American-Made Brands Are Dealing With Domestic Dead Ends

Brands and retailers who proudly declare they’re “made in the USA” have serious challenges brimming beneath their patriotic polish.

The fashion industry has become far removed from America: 97 percent of the world’s clothing manufacturing happens abroad. American shopping habits have changed as a result: In 1965, 95 percent of the clothing Americans purchased was made in the U.S. Today, it’s 2 percent.

Modern brands who tout themselves as all-American are playing into a particular emotional hook that hopes to attract customers who want to know where their garments were made. If clothing is made in America, customers can rest assured that they weren’t made in a factory that flouts ethical and environmental guidelines.

American-made brands, however, tend to skew niche and small-scale. Brands that once made every product in the U.S., like Red Wings and New Balance, have shifted production of most products overseas, while L.A.-made American Apparel has filed Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Current all-American made retailers, meanwhile, zoom in on limited quantities of one product. Examples include Tanner Goods, a leather accessories brand, New England Shirt Co., a men’s shirts brand, and Oak Street Bootmakers, a footwear company.

“It’s much easier to manufacture overseas,” said Todd Shelton, the founder of an American clothing brand of the same name that is manufactured in New Jersey. “It’s logistically possible [to stay in America], but it’s very easy to be tempted by the convenience of manufacturing elsewhere, especially if you want to scale.”

As retailers look to scale or expand into new categories, they have to resist that temptation in order to stay in line with the brand positioning they’ve built their businesses around. Customers who shop — and are willing to spend more — for made-in-America products depend on the businesses they support to stay true to that standard. But with fewer resources in the U.S., American-made brands are dealing with complexities up and down the supply chain, which are reflected in marketing strategies.

For some brands, fabric sourcing has run dry

Operating an American-made brand isn’t impossible, but trying to source different fabrics and materials in the U.S. can lead to dead ends.

American Giant has built its retail business by sourcing and manufacturing in the U.S., but that’s because the brand has, so far, specialized in knitwear like sweatshirts and T-shirts, which are made from North Carolina cotton. CEO Bayard Winthrop said that as the company looks to launch products made with other fabrics, like merino wool or dyed woven shirts, it will have to explain the process and reasoning behind sourcing off U.S. soil.

“If you’re American-made, you have to be comfortable with letting your customers come in,” said Winthrop. “Our posture has been that we want to be biased toward American-made. The most preferable thing to do is stay domestic. But as you expand, you run into problems.”

Getting merino wool from its source, New Zealand, would be an easy thing to explain to customers. Winthrop said that if demand was there for wool sweaters, he wouldn’t dismiss it simply to avoid sourcing fabrics from overseas. But dyed woven shirt fabric is a category that used to be made in America. That process and material has since been outsourced in favor of cost efficiency, which is a conversation Winthrop hopes American Giant’s practices can raise.

“We want to be a force for good in that discussion,” he said. “If we can’t get something here, we shine a light on why we can’t. There are some things you just can’t get domestically, and our customers are interested in that conversation.”

Brands who position themselves as American-made have to factor for transparency, and for an uncertain future as the industry changes. Similar modern brands like Zady, Everlane and The Reformation use a transparent business model as the emotional hook for customers, rather than “made in America.”

“The approach should be to use that branding as a guiding beacon and a sense of purpose, not marketing collateral,” said Alex Tarnoff, senior consultant at branding agency Vivaldi. “But there are implications for how you grow and conduct operations. You have to be truly committed.”

“Pure capabilities are different”

Maintaining a made-in-the-USA status means not taking the easy way out for many brands. In order to avoid cutting costs by outsourcing for cheaper labor and environmental shortcuts, Winthrop said he weighs what he calls “soft costs.”

“It’s cheaper to take things overseas; that’s the truth,” he said. “But there are a lot of soft costs that are harder to monetize — which is how much do I waste on the water, or how are the people treated, and how easily can I communicate with my partners.”

Retailers need to maintain a discipline and focus on a greater mission in order to avoid cutting costs on manufacturing down the line. Todd Shelton built its own factory in New Jersey in order to dodge outsourcing labor, but in order to invest in that infrastructure, the company had to scale back on marketing and category expansion.

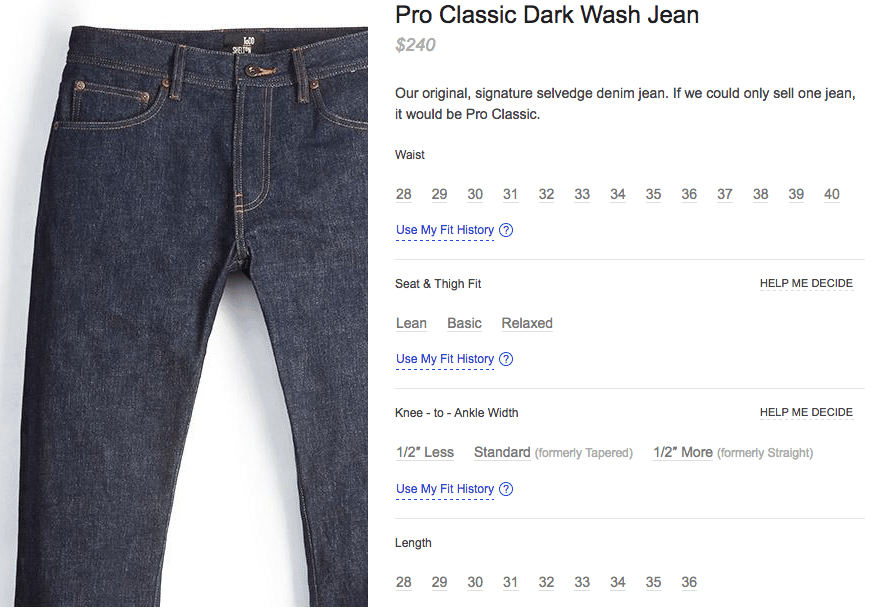

A Todd Shelton product page, which lets customers get very specific about sizing.

Overseas factories compete on more than just cheaper costs, however. For brands looking to create designs using advanced skill sets, like block printing or embroidery, they’ll have to look beyond American factories.

“Pure capabilities of factory workers are different,” said Jag Gill, founder of digital materials sourcing platform Sundar. “Plus, it’s supply and demand: The good factories are going to be blocked out by large companies that want to use them and smaller companies will have to compete. Their prices then go up as there’s more demand.”

She added that investment in manufacturing technology and quality in the U.S. has dwindled as the industry has gone elsewhere, and the country’s capabilities have become less sophisticated. But Tarnoff is hopeful that shifting consumer values will open up the road for smaller domestic brands.

“The road to scaling is more challenging and you have to be more thoughtful and purposeful,” he said. “But these brands aren’t necessarily limited. Customers root for the anti-big retailer.”

SOURCE: Glossy

It’s sad if we could have kept it made here to begin with, it’s like we have to start from scratch, reinventing the wheel, so to speak.