WASHINGTON (AFP) – Shuanghui International won the largest ever Chinese takeover of a US company Tuesday when shareholders of pork giant Smithfield Foods approved its $7.1 billion offer. The deal locks in for Shuanghui and the giant Chinese market a strong supply from the world’s largest pig raiser and pork processor.

U.S. households with income of more than $150,000 a year have an unemployment rate of 3.2 percent, a level traditionally defined as full employment. At the same time, middle-income workers are increasingly pushed into lower-wage jobs. Many of them in turn are displacing lower-skilled, low-income workers, who become unemployed or are forced to work fewer hours, the analysis shows.

“This was no `equal opportunity’ recession or an `equal opportunity’ recovery,” said Andrew Sum, director of the Center for Labor Market Studies at Northeastern University. “One part of America is in depression, while another part is in full employment.”

The findings follow the government’s tepid jobs report this month that showed a steep decline in the share of Americans working or looking for work. On Monday, President Barack Obama stressed the need to address widening inequality after decades of a “winner-take-all economy, where a few do better and better and better, while everybody else just treads water or loses ground.”

“We have to make the investments necessary to attract good jobs that pay good wages and offer high standards of living,” he said.

While the link between income and joblessness may seem apparent, the data are the first to establish how this factor has contributed to the erosion of the middle class, a traditional strength of the U.S. economy.

Based on employment-to-population ratios, which are seen as a reliable gauge of the labor market, the employment disparity between rich and poor households remains at the highest levels in more than a decade, the period for which comparable data are available.

“It’s pretty frustrating,” says Annette Guerra, 33, of San Antonio, who has been looking for a full-time job since she finished nursing school more than a year ago. During her search, she found that employers had become increasingly picky about an applicant’s qualifications in the tight job market, often turning her away because she lacked previous nursing experience or because she wasn’t certified in more areas.

Guerra says she now gets by doing “odds and ends” jobs such as a pastry chef, bringing in $500 to $1,000 a month, but she says daily living can be challenging as she cares for her mother, who has end-stage kidney disease.

“For those trying to get ahead, there should be some help from government or companies to boost the economy and provide people with the necessary job training,” says Guerra, who hasn’t ruled out returning to college to get a business degree once her financial situation is more stable. “I’m optimistic that things will start to look up, but it’s hard.”

Last year the average length of unemployment for U.S. workers reached 39.5 weeks, the highest level since World War II. The duration of unemployment has since edged lower to 36.5 weeks based on data from January to July, still relatively high historically.

Economists call this a “bumping down” or “crowding out” in the labor market, a domino effect that pushes out lower-income workers, pushes median income downward and contributes to income inequality. Because many mid-skill jobs are being lost to globalization and automation, recent U.S. growth in low-wage jobs has not come fast enough to absorb displaced workers at the bottom.

Low-wage workers are now older and better educated than ever, with especially large jumps in those with at least some college-level training.

“The people at the bottom are going to be continually squeezed, and I don’t see this ending anytime soon,” said Harvard economist Richard Freeman. “If the economy were growing enough or unions were stronger, it would be possible for the less educated to do better and for the lower income to improve. But in our current world, where we are still adjusting to globalization, that is not very likely to happen.”

The figures are based on an analysis of the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey by Sum and Northeastern University economist Ishwar Khatiwada. They are supplemented with material from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s David Autor, an economics professor known for his research on the disappearance of mid-skill positions, as well as John Schmitt, a senior economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, a Washington think tank. Mark Rank, a professor at Washington University in St. Louis, analyzed data on poverty.

The overall rise in both the unemployment rate and low-wage jobs due to the recent recession accounts for the record number of people who were stuck in poverty in 2011: 46.2 million, or 15 percent of the population. When the Census Bureau releases new 2012 poverty figures on Tuesday, most experts believe the numbers will show only slight improvement, if any, due to the slow pace of the recovery.

Overall, more than 16 percent of adults ages 16 and older are now “underutilized” in the labor market – that is, they are unemployed, “underemployed” in part-time jobs when full-time work is desired or among the “hidden unemployed” who are not actively job hunting but express a desire for immediate work.

Among households making less than $20,000 a year, the share of underutilized workers jumps to about 40 percent. For those in the $20,000-to-$39,999 category, it’s just over 21 percent and about 15 percent for those earning $40,000 to $59,999. At the top of the scale, underutilization affects just 7.2 percent of those in households earning more than $150,000.

By race and ethnicity, black workers in households earning less than $20,000 were the most likely to be underutilized, at 48.4 percent. Low-income Hispanics and whites were almost equally as likely to be underutilized, at 38 percent and 36.8 percent, respectively, compared to 31.8 percent for low-income Asian-Americans.

Loss of jobs in the recent recession has hit younger, less-educated workers especially hard. Fewer teenagers are taking on low-wage jobs as older adults pushed out of disappearing mid-skill jobs, such as bank teller or administrative assistant, move down the ladder.

Recent analysis by the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research shows that whites and older workers are more pessimistic about their opportunities to advance compared to other groups in the lower-wage workforce.

Eric Reichert, 45, of West Milford, N.J. Reichert, who holds a master’s degree in library science, is among the longer-term job seekers. He had hoped to find work as a legal librarian or in a similar research position after he was laid off from a title insurance company in 2008. Reichert now works in a lower-wage administrative records position, also helping to care for his 8-year-old son while his wife works full-time at a pharmaceutical company.

“I’m still looking, and I wish I could say that I will find a better job, but I can no longer say that with confidence,” he said. “At this point, I’m reconsidering what I’m going do, but it’s not like I’m 24 years old anymore.”

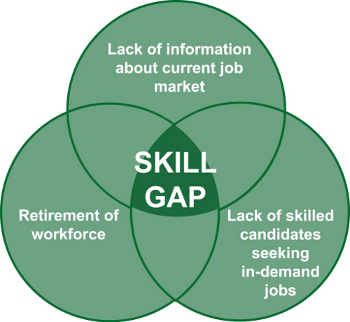

Will it be possible to fill this gap? If we are struggling to find skilled people today, where will we find them in the future, as the problem magnifies? How do we fix this problem? There is a lot of talk about STEM education as the solution. Many people wonder, “What the heck is STEM?” They are then told it means, “Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math.” But that’s not really a sufficient explanation.

Frankly, STEM starts with the basics that all people should master in a rudimentary education. The ability to read, write, do math, and think critically are all key pillars, complimented by the ability to show up on time, communicate effectively, and work in teams. People with these skills can be developed and trained to pursue a menagerie of career pathways. Without those foundational skills, the future is bleak.

Click Bond is the global leader in the design and manufacture of adhesive-bonded fasteners and whether we’re talking about an entry level accountant, assembly technician, a quality inspector, a top design engineer or the people who package and ship our product across the globe, all aspects of our operation require these foundational skill sets on a daily basis. Unfortunately, even with record unemployment numbers, it remains challenging to find people who can demonstrate these basic, fundamental skills.

Some allege that this gap isn’t real and that’s it’s just an acute problem: manufacturers are just too picky. Others say manufacturers don’t pay enough or contend that manufacturing just represents dirty, low-level jobs.

On the notion that we are too selective –the ability to read, write, do math, problem-solve, show up on time, communicate effectively and work in teams isn’t some outrageous litmus test for employment; it’s the minimum threshold to have a chance at a future on any career path.

As for the argument that our pay is too low — in 2011, the average manufacturing worker in the United Sates earned $77,060 annually, including pay and benefits. The average worker in all industries earned $60,168. Additionally, manufacturing has the highest multiplier effect of any economic sector ($1.48 for every $1 spent).

With respect to our factories being dirty and our jobs being low level — people are constantly impressed with how clean and high tech manufacturing operations are in the 21st century. We sit at the forefront of environmental, safety, technology, security and quality standards. We can’t compete globally otherwise.

Beyond these misperceptions, the reality is, the greatest asset we have is our people. This explains why the vast majority of manufacturers fund robust training and education programs in partnership with our local high schools, community colleges and universities.

In Nevada we are engaging with leaders in higher education — especially our community colleges — to ensure that their investments in facilities and curriculum are worthwhile. Last year, we helped deploy a training program that, in just 16 weeks, takes people from the unemployment lines to full time jobs as machine operators. Well over 90% of the graduates achieved full time employment with benefits!

We also partner with workforce development leaders to ensure that training dollars are aligned with the current and future needs of the marketplace. When these needs are aligned with nationally portable, industry-driven credentials, everyone wins. The training provider gains absolute clarity on the quality of instruction necessary for a successful program, and the student earns a viable credential that proves mastery of a skill.

Further, through proactive engagement with our community and by opening the doors of our factories to students, teachers, parents and the broader community, we are dispelling antiquated stereotypes and, once again, getting people excited about “Made in the USA”.

The parts we make at Click Bond help make our fighter jets safer and ensure that millions of people can travel safely around the world without incident. Our colleagues are developing exciting technology and products that are achieving remarkable breakthroughs in medicine, renewable energy, IT, transportation, logistics and so much more. The reality is: manufacturing makes America strong. And all of us must work together to keep it that way.

During the first half of this year, the trade deficit on trade of manufactured goods narrowed to $225 billion from $227 billion a year ago, the Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation reported Tuesday. While small, the Arlington, Va.-based research group considers the development a positive sign, especially after years of steep deficits.

The report follows another one released Tuesday, which expects U.S. manufacturing to make a comeback — potentially creating 2.5 million to 5 million factory and service jobs associated with more U.S. manufacturing over the next seven years. Boston Consulting Group says the shift is being driven by a variety of factors: Lower costs of natural gas and electricity have given U.S. manufacturers an advantage over other countries; so has the rising cost of labor in China, where the U.S. had lost many manufacturing jobs to.

One other factor — indeed, a big one — that deserves extra attention is the decline of labor costs in the U.S.

While cheaper labor has made manufacturers more likely to hire, it also means less income and spending power for workers.

Understandably many people get nostalgic whenever Washington policymakers and corporate America talk about reclaiming all that was good about U.S. manufacturing during its heyday. It takes us back to a time when the average American could buy a house and raise a family by working at the local factory until retirement. In some ways, the Obama Administration has indulged this vision of America; it has made a manufacturing recovery a top priority.

And yet, it’s hard to get that excited when we look at wages today and where they could go years from now.

A mediocre job is better than no job at all, especially at a time when so many struggle to find work. Manufacturing may create more jobs than it had in recent years, but it won’t renew America’s shrinking middle class so long as wages continue to stagnate.

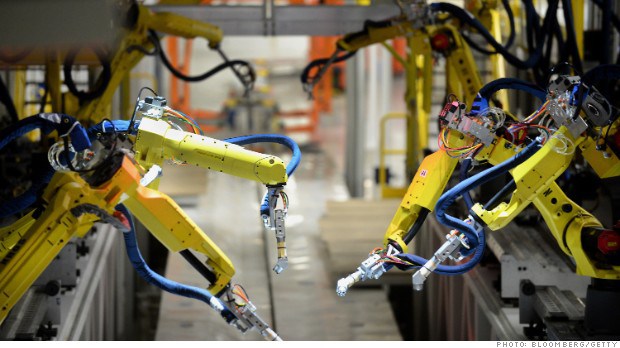

The reality is U.S. factories rely more on machines than actual workers, says Jesse Rothstein, public policy and economics professor at University of California Berkeley. Machines produce more for less, and with bargaining powers of U.S. unions not being what they once were, it becomes less likely workers will earn more.

In a 2012 study, Rothstein found that hires by manufacturers of durable goods (items lasting three years or more) were paid an average of 0.3% less in 2010 and 2011 than workers newly hired in 2007 and 2008.

A similar trend plays out if we look at manufacturing overall: The average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees were $8.43 for 2012, lower than $8.70 in 2009 and $8.75 in 2003, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. To be sure, some higher-skilled manufacturing jobs, such as welding, have seen wages rise.

The Boston Consulting Group notes the U.S. is steadily becoming one of the cheapest places in the developed world to manufacture. By 2015, average labor costs will be about 16% lower in the U.S. than in the U.K., 18% lower than in Japan, 34% lower than in Germany, and 35% lower than in France and Italy.

If the firm is right, it’s likely that many more manufacturers will return jobs to the U.S., as it predicts. However, if trends in pay continue, it probably won’t rebuild the middle class.

NEW YORK, Sept. 24, 2013 /PRNewswire-USNewswire/ — Top leaders of the United Steelworkers (USW) confirmed being joined by the Alliance for American Manufacturing (AAM) and steel bridge fabricators in a meeting this past week led by the New York governor’s office, plus public authority transportation officials to consider ways to support sourcing American-made steel and domestic construction products in upcoming infrastructure projects.

“So we welcomed a face-to-face agenda on what to do about it.”

USW leaders in the meeting were Tom Conway, international vice president from Pittsburgh; and John Shinn, director of USW District 4 in New York, who also represents the union membership in New Jersey and the New England states. Participating for NY State were MTA Chairman Tom Prendergast, State Deputy Secretary Karen Rae, and NY-NJ Port Authority Executive Director Pat Foye. Senior officers of the Washington-based AAM made presentations.

USW Vice President Conway said, “Meeting with MTA and the Port Authority was a good start, but actions speak louder than words. We’ll need to see better results in the future when MTA makes sourcing decisions on major infrastructure projects.”

Shinn of USW District 4 added: “We had a productive meeting with the top decision makers from the governor’s office and both the MTA and Port Authority. We came away encouraged by their willingness to share information and their offer to meet on a regular basis.”

The USW regional director, who served with the governor’s ‘New York State 2100 Commission’ on infrastructure, emphasized there were challenges ahead. “Supporting a domestic supply chain of American workers that are not dependent on offshore labor or materials for bridge projects needed by the two agencies in the northeast corridor may require changes in the procurement process.”

According to the USW, the NY officials responded to criticism of the Verrazano Bridge contract with China steel by expressing interest in reevaluating and strengthening the Buy America steel preference used by MTA, which has not changed since its adoption in 1983. There was also broad agreement that the unreasonable agency cost waiver – currently available when domestic steel is six percent more expensive – needs to be increased.

“This would be an important step in leveling the playing field for the U.S. industry and workers in their competition with foreign state-owned enterprises that benefit from generous government subsidies,” Conway said. “We intend to hold them to their word that real reforms will be made both to their internal practices and with respect to state-level laws. Their public support for such reforms will be necessary to ensure that no more bridges or public works are outsourced.”

In mid-July, U.S. Senators Charles Schumer (D-NY) and Sherrod Brown (D-OH) urged the MTA: “If we continue to source to Chinese companies based entirely on bid pricing, they will always win – with the level of government support and overproduction, it’s impossible to beat their prices. This is causing a global race to the bottom on steel prices, a budding environmental catastrophe and the threatening of steel production not just in the U.S., but worldwide.”

New York State AFL-CIO President Mario Cilento and USW Director Shinn wrote to state legislators and affiliate unions, “It is beyond disappointing that a New York State public authority would undermine our economy and jobs by offshoring our major infrastructure needs, which should be American made, to China.

“Our state has lost nearly half its manufacturing capacity in the past twenty years. The consequences have been job loss, decreased economic opportunity and competitiveness. Irresponsible actions by public agencies like the MTA will only make things worse.”

In the coming weeks and months, AAM will be convening meetings in Washington, DC, and in New York with the goal of supporting a more proactive approach to infrastructure projects involving American workers and manufacturers. For more information: www.americanmanufacturing.org/.

The USW is the largest industrial union in North America, representing 850,000 workers employed in the manufacturing, service and resource sectors of steel, mining, concrete, paper, rubber, chemicals, metal fabrication, transportation and energy sources that include oil refining and renewables. For more information: www.usw.org/.

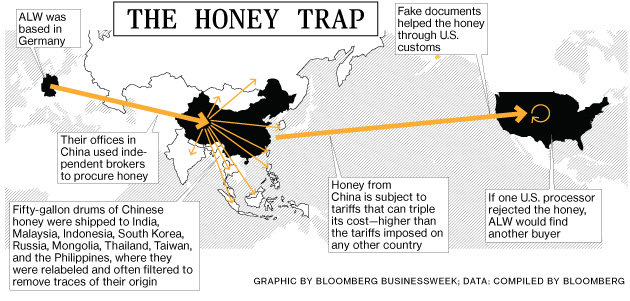

On March 24, 2008, von Buddenbrock came to the office around 8:30 a.m., as usual. He was expecting a quiet day: It was a holiday in Germany, and his bosses there had the day off. Giesselbach was on holiday, too; she had returned to Germany to visit her family and boyfriend. Sometime around 10 a.m., von Buddenbrock heard a commotion in the reception area and went to have a look. A half-dozen armed federal agents, all wearing bulletproof vests, had stormed in. “They made a good show, coming in with full force,” he recalls. “It was pretty scary.”

The agents asked if anybody was hiding anywhere, then separated von Buddenbrock and his assistant, the only two employees there. Agents brought von Buddenbrock into a conference room, where they questioned him about ALW’s honey business. After a couple of hours they left, taking with them stacks of paper files, copies of computer hard drives, and samples of honey.

Giesselbach returned from Germany three days later. Her flight was about to land at O’Hare when the crew announced that everyone would have to show their passports at the gate. As Giesselbach walked off the plane, federal agents pulled her aside. She, too, answered their questions about ALW’s honey shipments. After an hour, they let her leave. The agents, from the U.S. Department of Commerce and the Department of Homeland Security, had begun to uncover a plot by ALW to import millions of pounds of cheap honey from China by disguising its origins.

Von Buddenbrock and Giesselbach continued to cooperate with the investigators, according to court documents. In September 2010, though, the junior executives were formally accused of helping ALW perpetuate a sprawling $80 million food fraud, the largest in U.S. history. Andrew Boutros, assistant U.S. attorney in Chicago, had put together the case: Eight other ALW executives, including Alexander Wolff, the chief executive officer, and a Chinese honey broker, were indicted on charges alleging a global conspiracy to illegally import Chinese honey going back to 2002. Most of the accused executives live in Germany and, for now, remain beyond the reach of the U.S. justice system. They are on Interpol’s list of wanted people. U.S. lawyers for ALW declined to comment.

In the spring of 2006, as Giesselbach, who declined requests for an interview, was preparing for her job in Chicago, she started receiving e-mail updates about various shipments of honey moving through ports around the world. According to court documents, one on May 3 was titled “Loesungmoeglichkeiten,” or “Solution possibilities.” During a rare inspection, U.S. customs agents had become suspicious about six shipping containers of honey headed for ALW’s customers. The honey came from China but had been labeled Korean White Honey.

The broker, a small-time businessman from Taiwan named Michael Fan, had already received advice from ALW about how to get Chinese honey into the U.S. ALW executives had told him to ship his honey in black drums since the Chinese usually used green ones. And they had reminded him that the “taste should be better than regular mainland material.” Chinese honey was often harvested early and dried by machine rather than bees. This allowed the bees to produce more honey, but the honey often had an odor and taste similar to sauerkraut. Fan was told to mix sugar and syrup into the honey in Taiwan to dull the pungent flavor.

After Fan’s honey shipment was confiscated, an ALW executive wrote to Giesselbach and her colleagues: “I request that all recipients not to write e-mail about this topic. Please OVER THE TELEPHONE and in German! Thank you!”

Nonetheless, Giesselbach and executives in Hamburg, Hong Kong, and Beijing continued to use e-mail for sensitive discussions about the mislabeled honey. When Yan Yong Xiang, an established honey broker from China they called the “famous Mr. Non Stop Smoker,” was due to visit Chicago, Giesselbach received an e-mail. “Topic: we do not say he is shipping the fake stuff. But we can tell him that he should be careful on this topic + antibiotics.” E-mails mention falsifying reports from a German lab, creating fake documents for U.S. customs agents, finding new ways to pass Chinese honey through other countries, and setting up a Chinese company that would be eligible to apply for lower tariffs. Giesselbach comes across as accommodating, unquestioning, and adept.

ALW relied on a network of brokers from China and Taiwan, who shipped honey from China to India, Malaysia, Indonesia, Russia, South Korea, Mongolia, Thailand, Taiwan, and the Philippines. The 50-gallon drums would be relabeled in these countries and sent on to the U.S. Often the honey was filtered to remove the pollen, which could help identify its origin. Some of the honey was adulterated with rice sugar, molasses, or fructose syrup.

In a few cases the honey was contaminated with the residue of antibiotics banned in the U.S. In late 2006 an ALW customer rejected part of Order 995, three container loads of “Polish Light Amber,” valued at $85,000. Testing revealed one container was contaminated with chloramphenicol, an antibiotic the U.S. bans from food. Chinese beekeepers use chloramphenicol to prevent Foulbrood disease, which is widespread and destructive. A deal was made to sell the contaminated honey at a big discount to another customer in Texas, a processor that sold honey to food companies. According to court documents, ALW executives called Honey Holding the “garbage can” for the company’s willingness to buy what others would not. Giesselbach followed up with Honey Holding, noting “quality as discussed.” The contaminated container was delivered on Dec. 14, 2006.

Von Buddenbrock’s introduction to the honey-laundering scheme came months after he’d settled into Chicago. In the spring of 2007 he was getting ready to take over the U.S. operation from a university friend, Thomas Marten. They talked about the business every other

week f

or a couple of hours over dinner. One night at an Italian restaurant near their office, Marten told von Buddenbrock about ALW’s mislabeling Chinese honey to avoid the high tariffs. “The conversation started normally,” says von Buddenbrock. “Then he started talking about honey. I always took notes in all our meetings, and I tried to take notes then. He told me I shouldn’t. I was surprised and a bit shocked about what I was hearing. We were talking about something criminal, and some people imagine meeting undercover, in a shady garage.” They were out in the open, eating pasta. Marten could not be reached for comment.

Von Buddenbrock took over from Marten in August 2007. The raid on the ALW office on North Wabash Avenue occurred seven months later, after U.S. honey producers had warned Commerce and Homeland Security that companies might be smuggling in cheap Chinese honey. Low prices made them suspicious. So did the large amount of honey suddenly coming from Indonesia, Malaysia, and India—more, in total, than those countries historically produced.

Although the illicit honey never posed a public health threat, the ease with which the German company maneuvered suggests how vulnerable the food supply chain is to potential danger. “People don’t know what they’re eating,” says Karen Everstine, a research associate at the National Center for Food Protection and Defense. The honey business is only one example of an uncontrolled market. “We don’t know how it works, and we have to know how it works if we want to be able to identify hazards.”

After they were questioned in March 2008, von Buddenbrock and Giesselbach continued to work for ALW. “We didn’t know what direction this was going to go,” says von Buddenbrock. “I was considering leaving, but I thought this might actually be a good opportunity for me.” If ALW got out of the honey business, he could focus on selling the products he knew more about. The ALW executives in Hamburg, he notes, kept in touch by e-mail but for obvious reasons no longer traveled to the U.S. Giesselbach, meanwhile, arranged to return to ALW’s Hamburg office; it’s not clear if she was being sent home by the company. Her flight to Germany was on Friday, May 23.

Von Buddenbrock drove her to O’Hare, hugged her goodbye beside the curb, and got back in his car. It was late afternoon, the beginning of Memorial Day weekend, and he called his assistant to see if he needed to return to the office. While he was on the phone, an unmarked Chevy Impala drove up behind him. Officials shouted for him to pull over, arrested him, and drove him to a downtown Chicago courthouse where Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents, federal prosecutors, and his lawyer were waiting. About 20 minutes later, Giesselbach was brought in. She had been arrested before she checked in for her flight. “We were not allowed to talk, but I could see on her face that she was shocked,” says von Buddenbrock. “We were both in complete disbelief.”

Von Buddenbrock had also booked a flight to Germany for the following week; he planned to attend a friend’s wedding and return to Chicago. “I think that made the agents nervous,” he says. “At that point they didn’t know the complexity of the scheme. They probably thought No. 1 and No. 2 are leaving the country.”

He and Giesselbach were charged with conspiring to import honey from China that was mislabeled and adulterated. They were taken next door to the Metropolitan Correctional Center, where they turned over their belongings, put on orange jumpsuits, and waited. “I was tense and nervous,” says von Buddenbrock. “But I managed to get along. I speak Spanish. I like soccer.” He played Monopoly with someone’s contraband dice. He got to know Joey Lombardo, the mafia boss. “He gave me a recommendation for an Italian restaurant.”

Back in Hamburg, Wolff told local newspaper Abendblatt: “The accusations against us are unfounded, and we will fight them with every legal means.”

On Monday, June 2, agents seized thousands more files from ALW’s office. Later that month, Giesselbach and von Buddenbrock were released after posting bond and continued to cooperate. “At first we didn’t have any clue how big it was,” says Gary Hartwig, the ICE special agent in Chicago in charge of the investigation.

|

ALW soon closed its U.S. operations and cut off contact with Giesselbach and von Buddenbrock. “ALW had such a nice scheme that functioned so well for a while,” says T. Markus Funk, an internal investigations and white-collar defense partner at Perkins Coie who was a federal prosecutor in Chicago when the ALW investigation began. “They were extremely sophisticated and intelligent in some ways, but so sloppy in other ways. What do they think—no one can translate German?”

|

|

Giesselbach and von Buddenbrock each pleaded guilty to one count of fraud in the spring of 2012. According to Giesselbach’s plea agreement, between November 2006, when she arrived in Chicago, and May 2008, when she was arrested, as much as 90 percent of all honey imported into the U.S. by ALW was “falsely declared as to its country of origin.”

In February 2010, Wolff & Olsen, the century-old conglomerate that owned ALW, sold it to a Hamburg company called Norevo. According to an affidavit by one of the ICE agents, the sale was a sham; a former ALW executive assured customers in the U.S. by e-mail that after the sale was complete it would be “business as usual.” The transaction price was not disclosed. Norevo replied to a request for comment with a statement that had been posted on its website in March 2010. It concludes: “Within the frame of this acquisition, as legally required, the whole staff [of ALW] was taken over by Norevo, allowing for the business continuity of the company.”

Giesselbach went to jail. For one year and one day, she was Prisoner 22604-424 at Hazelton, a federal penitentiary in Bruceton Mills, W. Va. In a sentencing memo, Giesselbach’s lawyer wrote of his client: “She was living her youthful dream of international travel and business; under those circumstances she ignored her good judgment and went along with her predecessor’s scheme knowing it was wrong.” Giesselbach was released on Sept. 8 and is being deported. Von Buddenbrock was put under home confinement in Chicago for six months. His last day in an ankle bracelet was Friday, March 8. On the Monday after that, he self-deported. “I was relieved and happy, but I wasn’t sure what’s going to come,” he says. He’s settling back into life in Germany. “At the beginning it was a bad, lone wolf, so to speak,” he says. “Later, digging deeper the government found it was more than just ALW. A lot of people were doing it. It was an open secret.”

A second phase of the investigation began in 2011, when Homeland Security agents approached Honey Holding, ALW’s “garbage can,” and one of the biggest suppliers of honey to U.S. food companies. In “Project Honeygate,” as agents called it, Homeland Security had an agent work undercover for a full year as a director of procurement at

Honey Holding.

In February 2013, the Department of Justice accused Honey Holding, as well as a company called Groeb Farms and several honey brokers, of evading $180 million in tariffs. Five people pleaded guilty to fraud, including one executive at Honey Holding, who was given a six-month sentence. Honey Holding and Groeb Farms entered into deferred prosecution agreements, which require them to follow a strict code of conduct and to continue cooperating with the investigation.

When it announced the deferred prosecution agreement, Groeb Farms, which is based in Onsted, Mich., said it dismissed two executives who created fake documents and lied to the board of directors even as the company’s own audits raised concerns that honey was being illegally imported. “Everything we are doing at Groeb Farms this year has been to ensure the integrity of our supply chain,” Rolf Richter, the company’s new CEO, said via e-mail. Groeb Farms paid a $2 million fine.

In a statement on its website, Honey Holding says it accepted full responsibility and that in its settlement “there will be neither admission of guilt nor finding of guilt.” The company, now called Honey Solutions, is paying its $1 million fine in installments.

Boston Consulting Group said its survey found most large U.S. companies now plan to move some production to America from China, or are “actively considering” the move.

The number of firms that have shifted manufacturing to the U.S. from China, or will do so in the next two years, has nearly doubled over the past 18 months.

The survey found the three main drivers of the trend are labor costs, product quality and a desire to be closer to customers.

As lower energy prices and declining labor costs make America a cheaper place to manufacture goods, China’s dynamics are also changing.

Once a source of cheap labor, the country is seeing its advantage squeezed by rising wage costs and an impending labor shortage.

More than 200 U.S.-based manufacturing companies with annual sales topping $1 billion took part in the Boston Consulting Group study.

A pick-up in manufacturing is a crucial plank in the American recovery story.

Already, several technology giants have shifted production back to the U.S. Google chief Eric Schmidt said it costs about the same to produce its Texas-made Moto X device locally as it would in Asia.

But a stronger push by technology firms to manufacture in the U.S. is unlikely. Most component suppliers for tech companies are based in Asia, while China has far more skilled engineers needed to meet swelling global demand for smartphones and devices than the United States.

Recent examples of companies announcing plans to shift production from China to the US include K’Nex, the toy manufacturer, Trellis Earth Products, which makes bioplastic goods such as bags and utensils, and Handful, the bra manufacturer.

The Boston Consulting Group survey found 21 per cent of a sample of 200 executives of large manufacturers were either already relocating production to the US, or planning to do so within the next two years. A further 33 per cent said they were considering it, or would consider it in the near future.

Those figures are sharply increased from a similar BCG survey early last year, which found 10 per cent of respondents moving production to the US, and a further 27 per cent considering or close to considering it.

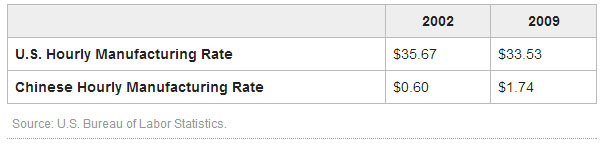

Labour costs were the factor most commonly cited by executives as determining location decisions, and China’s advantage has been slipping. Wage inflation has been running at about 15-20 per cent per year. Average hourly earnings in US manufacturing have risen just 1.6 per cent per year since 2011.

So far there has been little sign in the employment data of the improvement in the competitive position of US manufacturing. After bouncing back strongly from the trough of the recession, US manufacturing employment has stagnated for the past year at just under 12m.

However, Hal Sirkin of BCG said he expected the effect of reshoring would begin to show in the data over the next few years.

“These are leading indicators,” he said. “If you are going to have a plant up and running in 2015, you have to start planning in 2011, or 2012 at the latest.”

BCG is predicting that, by the end of the decade, reshoring and rising exports will have created 0.6m-1.2m new manufacturing jobs in the US.

The effect will vary across industries, BCG says. Prime candidates for reshoring are industries that have relatively lower labour costs, and relatively higher transport costs or other reasons to be close to their customers.

The US shale boom is also stimulating investment in industries that have high energy costs, particularly petrochemical production.

It headed to China, India, Mexico — wherever people would spool, spin and sew for a few dollars or less a day. Which is why what is happening at the old Wellstone spinning plant is so remarkable.

Drive out to the interstate, with the big peach-shaped water tower just down the highway, and you’ll find the mill up and running again. Parkdale Mills, the country’s largest buyer of raw cotton, reopened it in 2010.

|

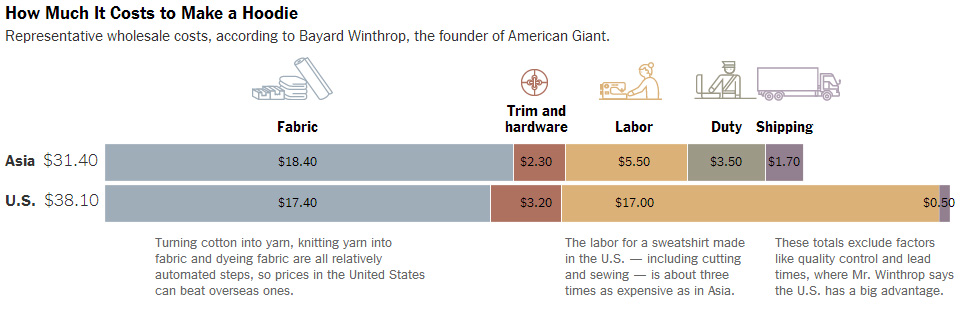

Bayard Winthrop, the founder of the sweatshirt and clothing company American Giant, was at the mill one morning earlier this year to meet with his Parkdale sales representative. Just last year, Mr. Winthrop was buying fabric from a factory in India. Now, he says, it is cheaper to shop in the United States. Mr. Winthrop uses Parkdale yarn from one of its 25 American factories, and has that yarn spun into fabric about four miles from Parkdale’s Gaffney plant, at Carolina Cotton Works.

Mr. Winthrop says American manufacturing has several advantages over outsourcing. Transportation costs are a fraction of what they are overseas. Turnaround time is quicker. Most striking, labor costs — the reason all these companies fled in the first place — aren’t that much higher than overseas because the factories that survived the outsourcing wave have largely turned to automation and are employing far fewer workers. |

Instead, he said, the road to Gaffney was all about protecting his bottom line.

That simple, if counterintuitive, example is changing both Gaffney and the American textile and apparel industries.

In 2012, textile and apparel exports were $22.7 billion, up 37 percent from just three years earlier. While the size of operations remain behind those of overseas powers like China, the fact that these industries are thriving again after almost being left for dead is indicative of a broader reassessment by American companies about manufacturing in the United States.

In 2012, the M.I.T. Forum for Supply Chain Innovation and the publication Supply Chain Digest conducted a joint survey of 340 of their members. The survey found that one-third of American companies with manufacturing overseas said they were considering moving some production to the United States, and about 15 percent of the respondents said they had already decided to do so.

|

“This is a completely different manufacturing paradigm than what we saw 10 years ago,” said David Simchi-Levi, a professor at M.I.T. who conducted the survey.

Beyond the cost and time benefits, companies often get a boost with consumers by promoting American-made products, according to a survey conducted in January by The New York Times. |

Now, companies that want to make things here often have trouble finding qualified workers for specialized jobs and American-made components for their products. And politicians’ promises that American manufacturing means an abundance of new jobs is complicated — yes, it means jobs, but on nowhere near the scale there was before, because machines have replaced humans at almost every point in the production process.

Take Parkdale: The mill here produces 2.5 million pounds of yarn a week with about 140 workers. In 1980, that production level would have required more than 2,000 people.

Curse of Long Distance

When Bayard Winthrop founded American Giant, he knew precisely what he wanted to make: thick sweatshirts like the one from the Navy that his father used to wear.

They required a dry “hand feel,” so the fabric would not seem greasy to the touch, and a soft, heavily plucked underside. Mr. Winthrop had already produced sportswear overseas, so he looked there for the advanced techniques and affordable pricing he needed.

He wanted to sell his hooded sweatshirt for around $80, between the $10 Walmart version, made in China, and the $125 Polo Ralph Lauren version, made in Peru. He was insistent on cutting and sewing the sweatshirts in the United States — a company called American Giant couldn’t do that part overseas, he felt — but wasn’t picky about where the fabric came from.

With the help of a consultant, he settled on a mill in Haryana, India, that could make the desired fabric. After several months of back-and-forth, Mr. Winthrop was ready to ship his first sweatshirts in February 2012.

|

But he was frustrated with the quality, and the lengthy process. By October of last year, Mr. Winthrop had moved production to South Carolina. Now it takes just a month or so, start to finish, to get a sweatshirt to a customer.

“We just avoid so many big and small stumbles that invariably happen when you try to do things from far away,” he said. “We would never be where we are today if we were overseas. Nowhere close.” |

There were also communication issues. Mr. Winthrop would send the Indian factory so-called tech packs that detailed exactly what kind of fabric he wanted and what variations he would allow. But even with photos and drawings, the roll-to-roll variance was big. And he couldn’t afford to fly to India regularly, or hire someone to monitor production there.

He also found that suppliers deferred to his wishes, rather than being frank about some of his choices, which weren’t, he conceded, always good ones.

“I’m a supporter of outsourcing when it makes sense,” he said. But it had stopped making sense.

Now that production has shifted to the United States, Mr. Winthrop says those problems have disappeared. Mr. Winthrop and his team visit Carolina Cotton Works and Parkdale whenever they want, check on quality and toss ideas around with the managers. And, he says, the cost is less than in India.

That’s when its clients started fleeing the United States.

The North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994 was the first blow, erasing import duties on much of the apparel produced in Mexico. The Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, when currencies collapsed, added a 30 to 40 percent discount to already cheaper overseas products, textile executives said. China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001 and quickly became an apparel powerhouse, and as of 2005, the W.T.O. eliminated textile quotas.

In 1991, American-made apparel accounted for 56.2 percent of all the clothing bought domestically, according to the American Apparel and Footwear Association. By 2012, it accounted for 2.5 percent. Over all, the American manufacturing sector lost 32 percent of its jobs, 5.8 million of them, between 1990 and 2012, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. The textile and apparel subsectors were hit even harder, losing 76.5 percent of their jobs, or 1.2 million.

“With all the challenges that we’ve had with cheap imports, we knew in order to survive we’d have to take technology as far as we could,” said Anderson Warlick, Parkdale’s chief executive.

The company began meeting with machine manufacturers, doing trial runs of equipment and offering feedback and debugging, so it got dibs on the newest technology. It looked for business opportunities in the countries where its customers were heading, those in Central America in particular, and now 75 percent of its business is in exports.

Over all, the company employs 4,000 people, its biggest work force ever, but it is technology that has made it competitive.

“We’ve been able to be effective here because we invested in our manufacturing to the point that labor is not as big of an issue as far as total cost as it once was,” Mr. Warlick said. “It’s allowed us to be able to compete more effectively with foreign countries that pay, you know, a fraction of what we pay in wages. We compete with them on technology and productivity.”

Back From the Dead

All that automation has made working in the mill — which once meant mostly dead-end jobs for people with no other options — desirable for many people.

Howard Taggert, 86, got his first mill job in 1948 after high school. “By being a color, yeah, you’ve got the worst jobs there was in textile,” said Mr. Taggert, who is African-American. “It was rough, but it was a living. We made a living.”

He started by opening cotton bales, which involved striking an ax onto a metal tie around the bales — a dangerous job, given that a spark from metal striking metal could ignite a room full of cotton. The dust was so thick that he couldn’t see to the next aisle, he said. He was paid 87 cents an hour.

“I had to. I didn’t have no other choice,” he said of working in the mills.

The work was so bad that Mr. Taggert refused to let his children go into mill work. He might be surprised to hear about Donna McKoy, who went back to work in a mill even after earning an associate degree in criminal justice.

Ms. McKoy, 47, lost her job at Continental Fabrics in North Carolina in the early 2000s, “when everything was downsizing and going over to China.” In 2001 alone, textile plants in the Carolinas eliminated 15,000 jobs. The sense of desperation was palpable, Ms. McKoy said.

“Now what?” she remembers asking herself before she decided to go to college.

After a headhunter contacted her in 2007, she became a supervisor at Parkdale, overseeing a night shift of 11 workers. The work — and the workplace — are barely recognizable compared with her job a decade ago. A couple of things struck her right away. First, the mill was clean. “Most open-end spinning plants that have the older model spinning frames in them are really dirty and dusty and not fun to be around,” she said. Thanks to the new technology, “my plant is always clean.”

Second, Ms. McKoy got training. For her first eight months, Parkdale paid for hotels, food, dry-cleaning and gas for trips home as she rotated around different factories and learned all of the jobs. And there were fewer people. Ms. McKoy now works at a plant in Walnut Cove, N.C., which she described as a smaller version of the Gaffney plant. On a typical 12-hour shift, Ms. McKoy said, two of the 11 people on her team fix the spinning machines about 4,000 times, with robots’ help.

She earns $47,000 a year and says the perks are good, like health care, an in-house nurse and monthly management classes for supervisors. She recently bought a three-bedroom house and owns a car.

“I have a comfortable life,” she said. “With this recession that we just had, I didn’t feel it.”

Scott Symmonds, 40, of Galax, Va., works as a technician for two plants in the area. He never planned on manufacturing work, but after time in the National Guard in Iraq, his home went into foreclosure and he had trouble getting work because of his low credit score and lack of a college degree. As a teenager in rural Iowa, he knew people who worked in manufacturing and watched two plants go out of business.

“I saw how they would come home dirty, smelly and often injured,” he said. “I didn’t want that.”

But he needed a job, and Parkdale was hiring. Mr. Symmonds started as a spinner, then got a job on the packing line, and then snagged a technician’s job after a technical-aptitude test. He earns $15 an hour, which he says is better than what competitors pay. He fears, though, that his higher pay could become a liability.

“We are making far more money than our counterparts in China or other nations,” he said. “We can’t afford to take a big enough cut in pay to be on an even level with those places.”

The story

Around 1990, China opened its doors to the global marketplace. By 2002, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated that China’s hourly manufacturing wage was only 1.68% of America’s hourly rate. In 2009, Chinese manufacturing labor costs were only 5.19% America’s costs.

Given this data, it is no wonder why my teacher’s family had such a difficult time finding inexpensive goods. American companies were quickly outsourcing work to China, saving boatloads of cash. But now the tide is turning.

With rising global fuel prices and labor prices rapidly increasing in China, American firms have been reassessing opportunities. We’re now beginning to see some of the results of their decisions.

Consider tech giants Google and Apple. They seem to have answered the nation’s plea to bring manufacturing jobs back to America. For example, Apple plans to invest $100 million to build Macs in America, while Google-owned Motorola Mobile is investing in U.S. manufacturing jobs. Regarding Motorola’s newest smartphone, Mark Randall, Motorola Mobile’s senior vice president of supply chain and operations, said:

We’re proud that Moto X is designed, engineered and assembled in the USA, but our decision to assemble here was also rooted in providing the best possible experience for consumers. … Assembling in the USA enables consumers in the USA to design their customized Moto X smartphones online and receive them in just a few days.

Other than running on Google’s newest Android operating system, the Moto X is customizable. As with building a custom vehicle, users can choose from nearly 2,000 combinations of features for the phone before it is assembled in Texas. As an added bonus, it is shipped free of charge within four business days of the order.

To be fair, many of the phone’s internal components are still made overseas. Regardless, Google is establishing a precedent, and consumers seem to like the results.

A recent Harris poll concluded that about 75% of consumers are willing to spend more money on American-made products while Gallup released a similar report in May that suggested only 60% of America’s population will pay more for U.S. products. Even with different results, we see a common thread: Americans will invest more if they think a product is made in America. Moreover, as the American economy improves, that increased production should boost stock prices for U.S. companies.

This phenomenon is even occurring within the automobile industry, where foreign automakers have dominated the market in recent history. For example, American car company Tesla Motors‘ stock has soared about 390% since April 2012. In the same time, Ford has jumped nearly 40%, while General Motors is up about 39%. But foreign manufacturer Honda has only increased about 1.9% in that time frame. Increasing consumer confidence, rising housing and auto markets, and improving economics — notably more comparable international manufacturing wages — all added to these firms’ stock price increases.

All things considered, though, the American automakers’ performance is exemplary. Ford now seems to have recovered from the 2008 crisis and has been profitable for 16 consecutive quarters. In fact, it is adding 1,400 manufacturing jobs in Detroit. Ford also plans to hire more than 6,000 employees to support its new products, growth, and long-term investments.

It is important to note, though, that like Google and Apple, most auto manufacturers are global firms. And given our globalized economy, it’s tough to draw clear comparisons between American carmakers and their foreign counterparts or to attribute the success of U.S. automakers to their U.S. operations.

That said, Tesla is making big waves. Tesla is stealing market share from foreign luxury auto-manufacturers like Mercedes and BMW. While it does not consider itself a luxury car manufacturer, Tesla is now the third-best-selling luxury car in California, America’s largest auto market. And although I question the firm’s ability to stabilize growth and anticipate a market correction, given its rapid market-share gains (in part because it has received government subsidies and because California residents receive subsidies if they purchase a Tesla made vehicle), Tesla is nonetheless further evidence that American-made goods are finding ample domestic interest.

In fact, American labor costs are comparable to, or lower than, some countries, especially after fuel and transportation costs are considered. As a result, foreign automakers are investing more capital in the U.S. Honda, for instance, operates nine manufacturing plants and 14 research and development facilities in America. Now, it is investing another $215 million in Ohio. Overall, it has $14 billion of capital tied up in the U.S.

Due to changing global conditions, U.S. labor costs are becoming more appealing, especially to companies headquartered in America. And many Americans seem to be interested in purchasing goods made domestically. Maybe my history teacher will be able to find American-made goods at comparable prices. I’ll be sure to ask the next time we correspond.

Profit From Global Growth

Profiting from our increasingly global economy can be as easy as investing in your own backyard. The Motley Fool’s free report “3 American Companies Set to Dominate the World” shows you how. Click here to get your free copy before it’s gone.

INQUIRIES

Media: PR Department

Partnership: Marketing

Information: Customer Service