Circumstances are no different in Jefferson and Lewis Counties, according to David J. Zembiec, deputy director of the Jefferson County Industrial Development Agency.

To remedy the situation, the JCIDA’s Manufacturing Council is planning to start an adult education course this fall to close the skills gap reported by local businesses.

The program will be geared toward training individuals for jobs that require more than a high school diploma but less than an associate degree, Mr. Zembiec said.

Companies are not only looking for basic skills such as welding but also for problem-solving skills and the ability to think conceptually.

The program, which will take students about four months to complete, will involve classes two to three times per week, Mr. Zembiec said.

The idea was developed through a partnership between manufacturing, education, workforce development and economic development officials, and its pilot run is taking place with the aid of donated materials from local manufacturers.

However, without additional help, the program will not be sustainable, Mr. Zembiec said.

To put the program on a more stable footing, its creators are applying to the North County Economic Development Council for additional funding. The goal is to run the program through the Jefferson-Lewis Board of Cooperative Educational Services with a permanently assigned instructor.

For now, the JCIDA has to find space to hold the pilot program, which it hopes to begin in the fall. It is currently seeking a location from BOCES or from a local manufacturer.

If the agency receives a grant from the economic development council, it will use the experiences from the test run to help structure a more formalized program, Mr. Zembiec said.

The goal of the program is three-fold, according to Mr. Zembiec:

■ To serve those who want to improve their career prospects.

■ To help manufacturers remain competitive and grow by making sure they have the workforce they need.

■ To encourage entrepreneurial enterprises.

At its Friday meeting, members of the Manufacturing Council also discussed the prospect of putting together a video aimed at changing preconceived notions about manufacturing held by middle school and high school students as well as their parents and guidance counselors.

M. Lynn Brown, general manager of WPBS-DT, Watertown’s public broadcasting station, was on hand along with two members of her staff to discuss ideas for the video.

Last year, the manufacturing sector was responsible for 12% of the nation’s total economic output. In Indiana, the state where manufacturing contributes most, the figure was 28.2%. 24/7 Wall St. reviewed the 10 states where manufacturing represented the largest total share of the state economy.

The states with the biggest manufacturing economies specialize in different industries. In Oregon, nearly $38 billion of the state’s $50 billion manufacturing sector came from computer and electronic product manufacturing. In Louisiana, more than 10% of the state’s entire economic output in 2011 came from the manufacturing of petroleum and coal-based products. Michigan and Indiana both have sizable auto industries, with Michigan’s auto industry accounting for slightly less than a third of all its manufacturing output in 2011.

During the recession, and in many cases before the recession even started, many states’ manufacturing employment faced steep job losses. Between January 2007 and mid-2009, Indiana lost more than 100,000 manufacturing jobs. In Michigan, nearly 125,000 manufacturing jobs were lost between January 2008 and January 2009 alone.

Now, many of these states have seen employment rebound. Michigan had the fastest job growth in the nation from the end of 2009 to the end of 2011. According to Chad Moutray, chief economist at the National Association of Manufacturers, “the auto sector has been one of the driving sectors in the economy, pardon the pun, over the course of the last couple of years.”

In addition to Michigan, many parts of the Midwest benefited as well, he added. In Indiana, employment has risen more than 3.5% a year for each of the past three years, especially impressive in the context of the nation’s slow job growth overall.

While some believe that the benefits of a potential manufacturing renaissance are largely a myth, Moutray told 24/7 Wall St. that investments in the sector have a positive impact on the economy overall. He also noted that the prospect of added jobs may appeal to many Americans because it jobs pay well.

To identify the 10 states where manufacturing matters, 24/7 Wall St. used state gross domestic product (GDP) figures published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. We determined from these data which states had the largest percentage of output attributable to manufacturing. Data on specific industries within the manufacturing sector from 2011 represent the most recent available figures. Employment figures for each state come from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and are seasonally adjusted.

Seasonally adjusted manufacturing job totals were not available for Alabama and Oklahoma.

These are the 10 states where manufacturing matters.

10. Alabama

- MFG share of output: 16.3%

- MFG output 2012: $30 billion (22nd highest)

- 2012 Unemployment rate: 7.3%

More than 16% of Alabama’s $183 billion worth of total output in 2012 came from manufacturing industries, about $30 billion. Last year, much of this output — $16.6 billion worth — came from the manufacturing of durable goods, which in 2012 accounted for 9.1% of total GDP, the ninth-highest percentage in the country. This includes the manufacturing of wood products, nonmetallic mineral products and so forth. News reports suggest a strong tradition of manufacturing in Alabama. Mobile County, for example, will now be the site of Airbus’s new A320 jetliner final assembly line, which will likely be the company’s first U.S.-based production facility. The project, which is scheduled to begin in 2015, is expected to create thousands of jobs, a welcome prospect in the wake of declining manufacturing industries this past decade.

9. Michigan

- MFG share of output: 16.5%

- MFG output 2012: $66.2 billion (8th highest)

- 2012 Unemployment rate: 9.1%

Each of the “Big Three” U.S. auto manufacturers — Chrysler, Ford and General Motors — is based in Michigan, and car sales are trending upward. This likely will be critical for the state: motor vehicle manufacturing accounted for nearly 5% of the state’s total GDP in 2011, far more than any other state. Michigan also led the nation with $18.8 billion in motor vehicle manufacturing output in 2011. The resurgence in the auto industry has not only boosted output but also led to job growth. Manufacturing employment in Michigan rose 7.9% between the ends of 2010 and 2011, leading all states, and then by an additional 3.9% between the ends of 2011 and 2012, also among the most in the nation. But this did little to help Detroit avoid a bankruptcy filing since extremely few auto manufacturing jobs exist within the city limits.

8. Iowa

- MFG share of output: 16.7%

- MFG output 2012: $25.4 billion (25th highest)

- 2012 Unemployment rate: 5.2%

Iowa had the 30th largest state economy in the nation last year. However, relative to its GDP, Iowa is still one of the nation’s largest manufacturers. This is especially the case for non-durable goods, which accounted for 8.4% of the state’s total output in 2012, the fifth-highest percentage in the nation. In 2011, when non-durable goods manufacturing accounted for 8.3% of Iowa’s output, nearly half of this contribution came from food, beverage and tobacco manufacturing. At 4% of state GDP, this was more than any other state except North Carolina. Despite low crop yields due to drought, Iowa was the leading producer of both corn and soybeans in 2012, according to the USDA.

7. Ohio

- MFG share of output: 17.1%

- MFG output 2012: $87.2 billion (5th highest)

- 2012 Unemployment rate: 7.2%

Ohio is a major manufacturer of a range of products. In 2011, it was one of the largest manufacturers of both primary and fabricated metals products, which together accounted for about 3% of the state’s output that year. The state was also the nation’s leader in producing plastics and rubber products, which accounted for more than $5.3 billion in output in 2011, or 1.1% of Ohio’s total output. Likely contributing to Ohio’s high output of manufactured rubber products, the state is home to Goodyear Tire & Rubber, a Fortune 500 company. At the end of 2012, Ohio was one of the top states for manufacturing employment, with roughly 658,000 jobs, trailing only far-larger California and Texas.

6. Kentucky

- MFG share of output: 17.1%

- MFG output 2012: $29.75 billion (23rd highest)

- 2012 Unemployment rate: 8.2%

In 2011, Kentucky manufactured nearly $4 billion worth of motor vehicles, bodies, trailers and parts, the fifth-largest output in the nation. As of 2011, this manufacturing industry was worth 2.4% of Kentucky’s GDP, the third-largest percentage in the country. In 2011, electrical equipment, appliance, and component manufacturing had an output of only about $1.3 billion the 15th highest, but this may be expected to improve. Louisville is home to the GE Appliance Park, where the company has recently built two new assembly lines. The assembly lines, which cost more than $100 million, will produce high-efficiency washing machines and will create about 200 jobs, in addition to the thousands of jobs GE has created in the region over the past few years with its opening of several other factories.

5. Wisconsin

- MFG share of output: 19.1%

- MFG output 2012: $49.98 billion (12th highest)

- 2012 Unemployment rate: 6.9%

Wisconsin led the nation in paper manufacturing in 2011, with nearly $4 billion in output, which was 1.5% of the state’s total GDP and the third-greatest portion of total output. In 2012, Wisconsin was a large producer of durable goods, which accounted for 11.3% of its GDP, up from 10.7% the previous year, holding on to its fourth place position. In spite of Wisconsin’s high output in the paper industry, the state’s Chamber of Commerce has expressed concerns regarding the implementation of government regulations that may hurt current and future job prospects. Officials in Wisconsin claim the new Boiler MACT regulations, for example, will have a negative economic impact on pulp and paper industry jobs in the state.

4. North Carolina

- MFG share of output: 19.4%

- MFG output 2012: $88.25 billion (4th highest)

- 2012 Unemployment rate: 9.5%

Last year, North Carolina was the fourth-largest manufacturing economy in the country, losing the third-place position to Illinois. In 2011, of the state’s $84 billion manufacturing output, nearly $24 billion alone came from chemical manufacturing.Roughly 5.5% of the state’s GDP arose from chemical manufacturing alone. Another close to $20 billion came from the food, beverage, and tobacco product industry, more than any state but California. North Carolina’s tobacco economy is one of the second-largest in the country, and R.J. Reynolds, the second-largest tobacco company by sales in the U.S., is based in the state.

3. Louisiana

- MFG share of output: 22.6%

- MFG output 2012: $55.10 billion (11th highest)

- 2012 Unemployment rate: 6.4%

None of the nation’s manufacturing leaders produced less output from durable goods manufacturing than Louisiana, at $7.7 billion. Similarly, in 2011, the state produced just $7.1 billion in manufactured durable goods. Louisiana was among the nation’s largest manufacturers of chemicals, as well as petroleum and coal products, that year, helping the state’s totals. As of 2011, more than 10% of the state’s GDP came from petroleum and coal manufacturing, by far the highest percentage in the nation. The state remains one of the nation’s leading oil refiners. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, “the Louisiana Offshore Oil Port (LOOP) is the only port in the U.S. capable of offloading deep draft tankers.”

2. Oregon

- MFG share of output: 27.8%

- MFG output 2012: $55.16 billion (10th highest)

- 2012 Unemployment rate: 8.7%

Oregon manufactured nearly $38 billion worth of computer and electronic products in 2011, up from the year before, and second in the nation. That output is behind California, but its percentage of total GDP was 20%, surpassing by far second place Idaho, where computer and electronic manufacturing accounts for only about 5.8% of total output as of 2011. Recent outside investments in the state reinforce the tech-heavy industries in Oregon. In the first half of this year, for example, AT&T invested nearly $80 million in its Oregon network to improve performance for Oregon residents, according to the Portland Business Journal.

1. Indiana

- MFG share of output: 28.2%

- MFG output 2012: $84.15 billion (6th highest)

- 2012 Unemployment rate: 8.4%

Indiana has added manufacturing jobs at one of the fastest rates in the nation over the past several years, with year-over-year growth in manufacturing at or above 3.7% at the end of each of the past three years. Some of this growth came from companies like Honda expanding their factories and adding thousands of jobs, which made headlines in 2011. Developments like these are critical for the economy of the state, which depends on manufacturing more than anywhere else in the nation. In 2012, Indiana had just the nation’s 16th largest economy, while its output from manufacturing exceeded all but a handful of states. In 2010 and 2011, Indiana was one of the leading states in total output from both motor vehicle-related and chemicals manufacturing. Manufacturing of chemical products accounted for 7% of the state’s GDP in 2011, at least partly due to the presence of pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly, which has vendors throughout the state.

24/7 Wall St.com is a financial news and commentary website. Its content is produced independently of USA TODAY.

See the top companies that are MAM Approved:

Learn how you can become a MAM brand ambassador and help support the Made in America Movement.

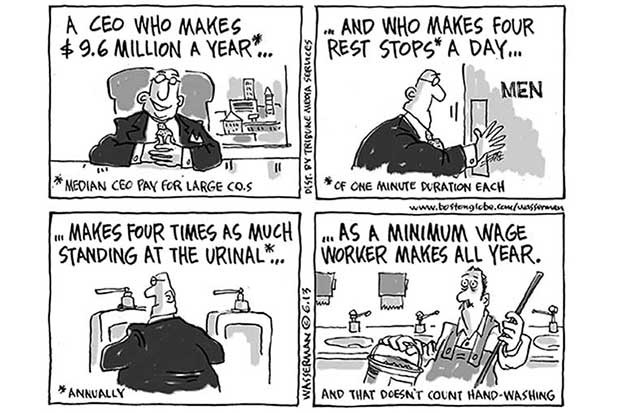

We built our business on wages above the minimum. For this small extra investment, we get long-term employees who are devoted to our company – employees whose ongoing relationships with customers have been vital to our success.

Good wages have been good business strategy in an industry that has seen more than its share of creative destruction. The last 20 years have been tough on the music business. In St. Louis, two-thirds of the record stores have closed since 2000. We’ve outlasted a 20-store local chain and numerous national and regional chains. Most of those companies paid their employees minimum wage or barely above. My creative, dedicated and better-paid employees won this life or death struggle for us.

Higher wages made us more competitive – not less. While my competition dealt with the costly results of constant employee turnover, constant training costs and the unsatisfied customers that turnover breeds, my employees added great value to my business.

Unfortunately, too many American companies have been driving down wages to poverty levels that are too low for workers to live on and too low to sustain the consumer demand that businesses need to survive and thrive. In a race to the bottom, the winner ends up at the bottom. The American Dream needs a minimum wage increase.

The current federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, just $15,080 for full-time work, is too low a floor under our workforce, our customers and our economy. Back in 1979, when we started our company, the minimum wage was $2.90 – that would be $9.33 in today’s dollars. Even back then, it had eroded from the 1968 minimum wage level, which would be $10.74 adjusted for inflation.

We never would have believed that 34 years later, the buying power of minimum wage workers – and millions of workers above minimum wage – would actually be lower than when we started our company. That’s terrible for small business, terrible for our economy and terrible for our country.

There’s a proposal in Congress to gradually raise the minimum wage to $10.10 over three years and then adjust it annually for inflation in the years following. It’s a reasonable proposal that moves us closer to where we would have been if the minimum wage had kept up with inflation since the 1960s.

Small business owners know that higher minimum wages put spendable dollars into the hands of our customers. Minimum wage earners, who live from paycheck to paycheck, spend increases right away. Putting a few hundred dollars more a month in their pockets would be a needed boon to business and the economy.

Companies that pay poverty wages count on other businesses and taxpayers to subsidize them. You may think of food stamps, housing assistance and child care subsidies as helping the poor, and they do, and it’s essential that we maintain them. But when wages are so low that full-time workers need the public safety net to put food on the table or keep a roof overhead, we are actually subsidizing the unrealistically low wages paid mostly by big highly profitable corporations. This perverts capitalism and is lousy public policy.

For example, in my state, according to the MO Healthnet Employer Report, in the first quarter of 2012 (latest data available) Walmart alone cost $6,247,032 in Medicaid costs. McDonalds cost $4,050,360 and Casey’s General Stores cost $1,473,094. Subway, Pizza Hut, Taco Bell and Sonic Restaurants cost more than $1 million dollars each. Together, these seven low-wage companies cost more than $16 million in Missouri taxpayer money in just three months.

A crucial part of my job as CEO is prediction and planning. Part of that is predicting costs and demand. Indexing the minimum wage to inflation, as Missouri and nine other states do now, would make it easier for businesses to predict and plan for labor costs. It would mean the buying power of our customers would not be hollowed out by an eroded wage floor.

Indexing is good for our tax base and our school systems, which are so dependent on property taxes. The most local small business is landlord. Most rental units are locally owned. The vast majority of low-wage workers are renters. A decent minimum wage helps maintain healthy property values and tax revenues.

The evidence that trickle-down economics doesn’t work is all around us. People are falling out of the middle class instead of rising into it. Putting money in the hands of people who desperately need it to buy goods and services will give us a trickle-up effect. Raising the minimum wage is a really efficient way to circulate money in the economy from the bottom up where it can have the most impact in alleviating hardship and boosting demand at businesses.

The American Dream isn’t functioning when the pie gets bigger, but the share for working people shrinks. Decent wages at the lowest rungs lets workers make ends meet while giving them a taste of the rewards of work.

Let’s keep the American Dream in sight for those farthest from experiencing its sweetest fruits.

Lew Prince is co-owner and CEO of Vintage Vinyl in St. Louis, Mo., and member of Business for a Fair Minimum Wage.

Recent news in and around the smartphone space points to an increasingly challenging environment:

- Weaker-than-expected shipments from Samsung;

- Weaker-than-expected June quarter shipments followed by price cuts and layoffs at Research in Motion – Blackberry;

- A sour outlook from HTC that calls for a sharp sequential drop in revenue;

- Apple AAPL -0.88%’s iPhone shipments fell 16.5% sequentially in the June quarter;

- Even though Nokia NOK -1.93%’s smartphone shipments grew 21% sequentially to 7.4 million units in the June quarter, the company’s average selling price dropped 17.8% on the same basis. The net result was had Nokia’s smartphone business revenues treading water.

After rattling those data points off, one would think the smartphone market is on a downward spiral, yet the latest figures from Strategy Analytics confirm the market continues to grow. In the June quarter, the third party research firm tabulated more than 229.6 million smartphones were shipped, up 10% from the March quarter and 47% compared to the year ago quarter. Looking at data from the GSM Association, there are more than 3.2 billion unique mobile subscribers as of August 2013 and that firm forecasts continued growth to 3.9 billion by 2017.

While there may be slower growth ahead, there is still growth to be had as smartphones continue to take share from basic and feature mobile phones. That shift is best seen in Nokia, which reported a sequential 4% drop in mobile phone shipments in the June quarter. On a year over year basis, the shift is far more evident as Nokia’s mobile phone shipments dropped nearly 27%.

PowerTalk with Motorola Mobility MMI NaN% on the Moto X and bringing jobs back to the U.S. One company that is doubling down on the smartphone opportunity is Motorola Mobility, which is now owned by Google, the company behind the Android mobile operating system. This past week the two companies introduced their first jointly developed smartphone – the Moto X – and I was fortunate enough to speak with Mark Randall, Motorola’s Senior Vice President of Supply Chain and Operation, about the Moto X and what it means for job creation here in the U.S. Mark was formerly of Amazon and as he tells me he helped design the Fort Worth plant where the Moto X will be assembled, back when he worked with Nokia.

During our conversation, Mark talks about the high degree of customization that is possible with the Moto X and while he is tight lipped about what may be next for Motorola Mobility he does point out the size of the Fort Worth, Texas facility. At roughly 500,000 square feet, Motorola and its partner Flextronics International aim to employ 2,200 people when the Moto X ramps to full production. Reading between the lines, it sounds like the Fort Worth facility could be the home for more products and potentially more jobs.

Given the market share gains by Chinese mobile phone and smartphone vendors like Huawei, ZTE and Lenovo, many are concerned about the about the ability to compete with those vendors and be profitable while manufacturing in the U.S. Given the high degree of customization that Motorola Mobility is offering with the Moto X, Mark points out it would have been far more difficult doing this with China based manufacturing partners. He also tells me the closeness of the design team and the manufacturing-assembly team was also crucial and that the labor costs between manufacturing in the U.S. and China were not as far off as many might think.

Moto X will be available in the US, Canada and Latin America starting in late August/early September at AT&T, Sprint Nextel, Verizon Communications, T-Mobile and other carriers as well as at Best Buy stores and Motorola.com.

Given the not only lower than expected job creation numbers reported in the July Employment Report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics but also the low quality nature of the report, the re-shoring of jobs by Motorola is welcome news.

While I am all for re-shoring jobs back to the U.S., as investors we have to wonder how successful the Moto X will be. The smartphone space is crazy competitive, and a single product can carry you only so far. Longtime followers of Motorola remember the RAZR craze, but without a killer follow-up product, Motorola soon began to lose its way. Time will tell how successful the Moto X will be and if there will be follow on products, but given its association with Google, Motorola Mobility now has some deep pockets to fall back on and that means it is far from out of the smartphone race. Those deep pockets are making a good sized bet on the Moto X given the $500 million in marketing and advertising that Google is going to spend on the new smartphone.

Because the Moto X will have a little more than one month of availability at best in the current quarter, that marketing and advertising blitz likely means even greater losses at Motorola for the near term. In the June quarter, Motorola Mobility lost more than $200 million on the operating line on $998 million in revenue. Some quick math shows that an incremental $500 million will sap $1 per share in earnings for Google in the coming quarters, but that’s small potatoes compared with the better than $43 per share that Google is expected to earn this year. If the product receives positive buzz, it will be a positive for Google shares.

My hometown — Port Clinton, Ohio, population 6,050 — was in the 1950s a passable embodiment of the American dream, a place that offered decent opportunity for the children of bankers and factory workers alike.

But a half-century later, wealthy kids park BMW convertibles in the Port Clinton High School lot next to decrepit “junkers” in which homeless classmates live. The American dream has morphed into a split-screen American nightmare. And the story of this small town, and the divergent destinies of its children, turns out to be sadly representative of America.

Growing up, almost all my classmates lived with two parents in homes their parents owned and in neighborhoods where everyone knew everyone else’s first name. Some dads worked in the local auto-part factories or gypsum mines, while others, like my dad, were small businessmen. In that era of strong unions and full employment, few families experienced joblessness or serious economic insecurity. Very few P.C.H.S. students came from wealthy backgrounds, and those few made every effort to hide that fact.

Half a century later, my classmates, now mostly retired, have experienced astonishing upward mobility. Nearly three-quarters of them surpassed their parents in education and in that way advanced economically as well. One-third of my classmates came from homes with parents who had not completed high school and, of that group, nearly half went to college.

Low costs at public and private colleges across Ohio were supplemented by locally raised scholarships — from the Rotary Club, the United Automobile Workers, the Junior Women’s Club and the like. Although the only two black students in my class encountered racial prejudice in town and none of their parents had finished grade school, both reached graduate school. Neither for them nor for our white classmates was family background the barrier to upward mobility that it would become in the next century.

J’s rise from a well-knit but modest working-class family to a successful professional career was not atypical, as a recent survey of my classmates revealed. My classmates describe our youth in strikingly similar terms: “We were poor, but we didn’t know it.” In fact, however, in the breadth and depth of the social support we enjoyed, we were rich, but we didn’t know it.

As we graduated, none of us had any inkling that Port Clinton would change anytime soon. While almost half of us headed off to college, those who stayed in town had reason to expect a steady job (if they were male), marriage and a more comfortable life than their parents’.

But just beyond the horizon a national economic, social and cultural whirlwind was gathering force that would radically transform the life chances of the children and grandchildren of the graduates of the P.C.H.S. class of 1959. The change would be jaw dropping and heart wrenching, for Port Clinton turns out to be a poster child for changes that have engulfed America.

The manufacturing foundation of Port Clinton’s modest prosperity in the 1950s and 1960s began to tremble in the 1970s. The big Standard Products factory at the east end of town provided nearly 1,000 steady, good-paying blue-collar jobs in the 1950s, but the payroll was more than halved in the 1970s. After two more decades of layoffs and “give backs,” the plant gates on Maple Street finally closed in 1993, leaving a barbed-wire-encircled ruin now graced with Environmental Protection Agency warnings of toxicity. But that was merely the most visible symbol of the town’s economic implosion.

Manufacturing employment in Ottawa County plummeted from 55 percent of all jobs in 1965 to 25 percent in 1995 and kept falling. By 2012 the average worker in Ottawa County had not had a real raise for four decades and, in fact, is now paid roughly 16 percent less in inflation-adjusted dollars than his or her grandfather in the early 1970s. The local population fell as P.C.H.S. graduates who could escape increasingly did. Most of the downtown shops of my youth stand empty and derelict, driven out of business by gradually shrinking paychecks and the Walmart on the outskirts of town.

Unlike working-class kids in the class of 1959, many of their counterparts in Port Clinton today are, despite toil and talent, locked into troubled, even hopeless lives. R, an 18-year-old white woman, is almost the same age as my grandchildren. Her grandfather could have been one of my classmates. But when I went off to college on a scholarship from a local employer, he skipped college in favor of a well-paid, stable blue-collar job. Then the factories closed, and good, working-class jobs fled. So while my kids, and then my grandchildren, headed off to elite colleges and successful careers, his kids never found steady jobs, were seduced by drugs and crime, and burned through a string of impermanent relationships.

His granddaughter R tells a harrowing tale of loneliness, distrust and isolation. Her parents split up when she was in preschool and her mother left her

alone an

d hungry for days. Her dad hooked up with a woman who hit R, refused to feed her and confined R to her room with baby gates. She says her only friend was a yellow mouse who lived in her apartment. Caught trafficking drugs in high school, R spent several months in a juvenile detention center and failed out of high school, finally eking out a diploma online. Her experiences left her with a deep-seated mistrust of anyone and everyone, embodied by the scars on her arms where a boyfriend injured her in the middle of the night. R wistfully recalls her stillborn baby, born when she was 14. Since breaking up with the baby’s dad, who left her for someone else, and with a second fiancé, who cheated on her after his release from prison, R is currently dating an older man with two infants born to different mothers — and, despite big dreams, she is not sure how much she should hope for.

R’S story is heartbreaking. But the story of Port Clinton over the last half-century — like the history of America over these decades — is not simply about the collapse of the working class but also about the birth of a new upper class. In the last two decades, just as the traditional economy of Port Clinton was collapsing, wealthy professionals from major cities in the Midwest have flocked to Port Clinton, building elaborate mansions in gated communities along Lake Erie and filling lagoons with their yachts. By 2011, the child poverty rate along the shore in upscale Catawba was only 1 percent, a fraction of the 51 percent rate only a few hundred yards inland. As the once thriving middle class disappeared, adjacent real estate listings in the Port Clinton News Herald advertised near-million-dollar mansions and dilapidated double-wides.

The crumbling of the American dream is a purple problem, obscured by solely red or solely blue lenses. Its economic and cultural roots are entangled, a mixture of government, private sector, community and personal failings. But the deepest root is our radically shriveled sense of “we.” Everyone in my parents’ generation thought of J as one of “our kids,” but surprisingly few adults in Port Clinton today are even aware of R’s existence, and even fewer would likely think of her as “our kid.” Until we treat the millions of R’s across America as our own kids, we will pay a major economic price, and talk of the American dream will increasingly seem cynical historical fiction.

Do you agree with the writer? Can you relate with the story? Please comment below.

A version of this article appeared in print on 08/04/2013, on page SR9 of the National edition with the headline: Crumbling American Dreams.

Until three years ago I did not believe in magic. But that was before I began investigating how western brands perform a conjuring routine that makes the great Indian rope trick pale in comparison. Now I’m beginning to believe someone has cast a spell over the world’s consumers.

This is how it works. Well Known Company makes shiny, pretty things in India or China. The Observer reports that the people making the shiny, pretty things are being paid buttons and, what’s more, have been using children’s nimble little fingers to put them together. There is much outrage, WKC professes its horror that it has been let down by its supply chain and promises to make everything better. And then nothing happens. WKC keeps making shiny, pretty things and people keep buying them. Because they love them. Because they are cheap. And because they have let themselves be bewitched.

Last week I revealed how poverty wages in India’s tea industry fuel a slave trade in teenage girls whose parents cannot afford to keep them. Tea drinkers were naturally upset. So the ethical bodies that certified Assam tea estates paying a basic 12p an hour were wheeled out to give the impression everything would be made right.

For many consumers, that is enough. They want to feel that they are being ethical. But they don’t want to pay more. They are prepared to believe in the brands they love. Companies know this. They know that if they make the right noises about behaving ethically, their customers will turn a blind eye.

So they come down hard on suppliers highlighted by the media. They sign up to the certification schemes – the Ethical Trading Initiative, Fairtrade, the Rainforest Alliance and others. Look, they say, we are good guys now. We audit our factories. We have rules, codes of conduct, mission statements. We are ethical. But they are not. What they have done is purchase an ethical fig leaf.

In the last few years, companies have got smarter. It is rare now to find children in the top level of the supply chain, because the brands know this is PR suicide. But the wages still stink, the hours are still brutal, and the children are still there, stitching away in the backstreets of the slums.

Drive east out of Delhi for an hour or so into the industrial wasteland of Ghaziabad and take a stroll down some of the back lanes. You might want to watch your step, to avoid falling into the stinking open drains. Take a look through some of the doorways. See the children stitching the fine embroidery and beading? Now take a stroll through your favourite mall and have a look at the shelves. Recognise some of that handiwork? You should.

Suppliers now subcontract work out from the main factory, maybe more than once. The work is done out of sight, the pieces sent back to the main factory to be finished and labelled. And when the auditors come round the factory, they can say that there were no children and all was well. Because audits are part of the act. Often it is as simple as two sets of books, one for the brand, one for themselves. The brand’s books say everyone works eight hours a day with a lunch break. The real books show the profits from 16-hour days and no days off all month.

Need fire extinguishers to tick the safety box? Hire them in for the day. The lift is a deathtrap? Stick a sign on it to say it is out of use and the inspector will pass it by. The dark arts thrive in the inspection business. We, the consumers, let them do this because we want the shiny, pretty thing. And we grumble that times are tight, we can’t be expected to pay more and, anyway, those places are very cheap to live in.

This is the other part of the magic trick, the western perception of the supplier countries, born of ignorance and embarrassment. India, more than most, knows how to play on this. Governments and celebrities fall over themselves to laud India for its progress. India is on the up, India is booming, India is very spiritual, India is vibrant. Sure, the workers are poor, but they are probably happy.

No, they are not. India has made the brands look rank amateurs in the field of public relations. Yes, we know it is protectionist, yes, we know working conditions are often diabolical, but we are in thrall to a country that seems impossibly exotic.

Colonial guilt helps. The British in particular feel awkward about India. We stole their country and plundered their riches. We don’t feel able to criticise. But we should. China still gets caught out, but wages have risen and working conditions have improved. India seems content to rely on no one challenging it.

Last week India’s powerful planning commission claimed that poverty was at a record low of 21.9% of the population. It did so on the basis that people could live on 26 rupees (29p) a day in rural areas (33 rupees in urban areas). Many inside India baulk at this. Few outside the country did so.

But times are tough, consumers say. This is the most pernicious of the ideas the brands have encouraged. Here’s some maths from anObserver investigation last year in Bangalore. We can calculate that women on the absolute legal minimum wage, making jeans for a WKC, get 11p per item. Now wave your own wand and grant them the living monthly wage – the £136 the Asia Floor Wage Alliance calculates is needed to support a family in India today (and bear in mind that the women are often the sole earners). It is going to cost a fortune, right? No. It will cost 15p more on the labour cost of each pair of jeans.

The very fact that wages are so low makes the cost of fixing the problem low, too. Someone has to absorb the hit, be it the brand, supplier, middleman, retailer or consumer. But why make this a bad thing? Why be scared of it?

Here is the shopper, agonising over ethical or cheap. What if they can do both? What if they can pluck two pairs of jeans off the rail and hold them up. One costs £20. One costs £20.15. It has a big label on it, which says “I’m proud to pay 15p more for these jeans. I believe everyone has the right to a decent standard of living. My jeans were made by a happy worker who was paid the fair rate for the job.”

Go further. Stitch it on to the jeans themselves. I want those jeans. I want to know I’m not wearing something stitched by kids kept locked in backstreet godowns, never seeing the light of day, never getting a penny. I want to feel clean. And I want the big brands and the supermarkets to help me feel clean.

I want people to say to them: “You deceived us. You told us you were ethical. We want you to change. We want you to police your supply chain as if you care. Name your suppliers. Open them to independent inspection. We want to trust you again, we really do, because we love your products. Know what? We don’t mind paying a few pennies more if you promise to chip in too.”

And here’s the best part: I think they would sell more. I think consumers would be happier and workers would be happier. And if I can spend less time trawling through fetid backstreets look

ing

for the truth, I’ll be happier.

August 2010

We revealed how factories supplying some of the biggest names on the British high street were making workers put in up to 16-hour days. Marks & Spencer, Gap and Next all launched inquiries and pledged to end excessive overtime.

November 2010

We revealed how Monsoon, the fashion chain that pioneered ethical shopping, used suppliers in India who employed child labour and paid workers below the minimum wage. Its global ethical trading manager urged the Indian government to tackle the issue. The company insisted it had a “long-lasting and passionate commitment to ethical trade”.

April 2011

We revealed how workers in China making iPhones and iPads for Apple suffered from illegal working hours and were made to write confession letters for minor misdemeanours. Foxconn, the Apple supplier, said it was trying to improve working conditions.

March 2012

Working with War on Want, we revealed how Bangladeshi workers producing sportswear for Olympic sponsors Adidas, Nike and Puma werebeaten, verbally abused, underpaid and overworked. The companies promised action

August 2012

The Observer, working with Indian anti-trafficking group Bachpan Bachao Andolan, revealed how boys as young as seven were sold to slave traders for work in the sweatshops of Delhi. Soon after the investigation, India’s government introduced new laws against child labour.

November 2012

We revealed claims that women in India who failed to hit impossible targets while making clothes for British high street names were berated, called “dogs and donkeys”, and told to “go and die”.

Daytona Beach News-Journal – DAYTONA BEACH — The purpose of the course, according to a flier from the college, is to help students “develop technical skills that can lead to certifications, internships and job interviews” at area manufacturers who have agreed to be partners in the program.

Jayne Fifer, CEO of the VMA, the Ormond Beach-based trade alliance that represents manufacturers throughout the Volusia-Flagler area and surrounding counties, has said in recent interviews that several of her members have been unable to fill available jobs because of a lack of skilled workers.

The classes will be held at Daytona State’s Advanced Technical College at 1770 Technology Blvd. in Daytona Beach.

For more information, call 386-506-3317.

Many economists expected the addition of 175,000 to 185,000 jobs in July and the average workweek to remain unchanged at 34.5 hours. The average workweek fell by 0.1 hour in July to 34.4 hours.

The monthly jobs report is closely watched by investors for signs that the Federal Reserve will soon taper its bond-buying efforts that have boosted the economy, perhaps leading to a new downturn. The Fed has indicated that it will pull back those purchases, but hasn’t said exactly when that will begin. Job additions have been moderate this year, but not at the level that will cause the jobless rate to fall substantially.

As interest rates edge up from record lows as the Fed reduces its stimulus, there is concern that bond investors will see more losses and the real estate market may cool.

“The report is disappointing, with weaker job growth in July compared to the first half of 2013,” PNC senior economist Gus Faucher said. “Despite the drop in the unemployment rate, the softer job growth in July, combined with the downward revisions to May and June, makes the Federal Reserve slightly less likely to reduce its purchases of long-term assets when it next meets in mid-September.”

Last month, the Labor Department reported a higher-than-expected addition of 195,000 jobs for June, though part-time work increased over 350,000 from May to June, reflecting weakness in the quality of jobs available. Friday’s report included revisions for previous months, lowering the number of jobs added in May to 176,000 from 195,000, and in June to 188,000 from 195,000.

Stephen Bronars, senior economist with Welch Consulting, said the unemployment rate has fallen, in part, because people are giving up their job searches and leaving the labor force.

The report indicated the labor force participation rate, which measures the percentage of adults who are either employed or jobless but actively looking for work, fell to 63.4 percent in July from 63.5 percent in June.

“Even more troubling is that the participation rate is down 0.3 percent from one year ago,” Bronars said.

Another concern, Bronars said, is that over the past two months, half of the gain in employment has been due to an increase in part-time jobs. In addition, there has been a substantial increase over the past two months in the fraction of full-time workers who are working part-time due to slack work and business conditions, he said.

The employment-population ratio was unchanged at 58.7 percent.

“This leaves us in a bit of a no man’s land, not quite close enough to taper, but a bit close enough to expectations that it looks like we have one more month of speculation about the Fed’s intention,” said Joe “JJ” Kinahan, chief strategist with TD Ameritrade.

The economy has been adding jobs for 34 straight months, since October 2010.

On Thursday, the Labor Department’s jobless claims report indicated the number of Americans applying for unemployment benefits fell 19,000 to 326,000, the fewest since January 2008.

On Wednesday, private payroll provider ADP reported employers added 200,000 jobs in July, the fastest pace since December.

And the Commerce Department’s GDP report showed the U.S. economy grew at an annual rate of 1.7 percent in the second quarter of this year, better than what most economists expected but showing only mild growth. In the first quarter, GDP rose only 1.1 percent.

“These rates of growth are about half of what is needed historically to support job gains of 200,000 per month,” said Robert Murphy, an economics professor at Boston College. “The reason for the higher level of job creation may be that employers postponed hiring early in the recovery until they were sure the expansion was on track. If so, then the recent level of job gains simply reflects postponed hiring that is not sustainable. Alternatively, the estimates of economic growth for this year may be revised upward in coming months as more complete data are compiled, supporting the job growth numbers.”

Carol Hartman from DHR International, an executive search firm, is especially concerned about the long term unemployed who are no longer counted in jobs reports.

“Steady job growth, while not robust, defies the tax increases, regulatory environment and large scale changes to healthcare,” she said. “Whether this anemic ‘recovery’ can pick up steam with more business and consumer costs and the financial distress of local municipalities remains to be seen.”

Written by: SUSANNA KIM (@skimm)

ABC News’ Zunaira Zaki contributed to this report.

Reposted from The New York Times:

How did this happen? The Metropolitan Transportation Authority says a Chinese fabricator was picked because the two American companies approached for the project lacked the manufacturing space, special equipment and financial capacity to do the job. But the United Steelworkers claims it quickly found two other American bridge fabricators, within 100 miles of New York City, that could do the job.

The real problem with this deal is that it doesn’t take into account all of the additional costs that buying “Made in China” brings to the American table. In fact, this failure to consider all costs is the same problem we as consumers face every time we choose a Chinese-made product on price alone — a price that is invariably cheaper.

Consider the safety issue: a scary one, indeed, because China has a very well-deserved reputation for producing inferior and often dangerous products. Such products are as diverse as lead-filled toys, sulfurous drywall, pet food spiked with melamine and heparin tainted with oversulfated chondroitin sulfate.

In the specific case of bridges, six have collapsed across China since July 2011. The official Xinhua news agency has acknowledged that shoddy construction and inferior building materials were contributing factors. There is also a cautionary tale much closer to home.

When California bought Chinese steel to renovate and expand the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, for a project that began in 2002, problems like faulty welds by a Chinese steel fabricator delayed the project for months and led to huge cost overruns. Those delays eroded much of the savings California was banking on when it opted for the “cheap” Chinese steel.

There is a second reason not to buy “Made in China” products: jobs. The abiding fact is that steel production is heavily subsidized by the Chinese government. These subsidies range from the massive benefits of a manipulated and undervalued currency to the underwriting of the costs of energy, land, loans and water.

Because of China’s subsidies — most of which are arguably illegal under international trade agreements — its producers are able to dump steel products into America at or below the actual cost of production. This problem is particularly acute now as China is saddled with massive overcapacity in its steel industry.

Of course, every job China gains by dumping steel into American markets is an American job lost. Each steelworker’s job in America generates additional jobs in the economy, along with increased tax revenues. With over 20 million Americans now unable to find decent work, we could certainly use those jobs as we repair the Verrazano Bridge.

The M.T.A. has ignored not only the social costs but also the broader impact on the environment and human rights. Chinese steel plants emit significantly more pollution and greenhouse gases per ton of steel produced than plants in the United States. This not only contributes to global warming but also has a direct negative impact on American soil, since an increasing amount of China’s pollution is crossing the Pacific Ocean on the jet stream.

Finally, when American companies and government agencies opt for Chinese over American steel, they are tacitly supporting an authoritarian regime that prohibits independent labor unions from organizing — one of many grim ironies in today’s People’s Republic. As a result, American workers are forced to compete against Chinese workers who regularly work 12-hour days, six or seven days a week, without adequate safety gear. Both Chinese and American steelworkers wind up as victims.

The bottom line here is this: Buying “Made in China” — whether steel for our bridges or dolls for our children — entails large costs that most consumers and, sadly, even our leaders don’t consider when making purchases. This is hurting our country — and killing our economy.

Peter Navarro, a professor of economics and public policy in the University of California, Irvine business school, directed the documentary film “Death by China.”

Making products ranging from bicycles to luxury watches and “sleeping bag” coats designed for the homeless, these small firms have tapped into a surprising amount of demand for goods made in a city more commonly associated today with failure and decline.

“Our customers come from all walks of life and are looking for a little bit of soul and something that is authentically Detroit,” said Eric Yelsma, founder of Detroit Denim Co., which produces hand-made jeans. “We can’t make them fast enough.”

Unlike deep-pocketed Dan Gilbert, co-founder of online mortgage provider Quicken Loans who has helped spur a downtown boom here by moving in 9,000 employees and spending $1 billion in the process, Detroit’s new entrepreneurs are winging it.

“None of us have ever done this before,” said Zak Pashak, who has invested $2 million in Detroit Bikes, which will start production of its “urban bike” model in August and aims to build 40,000 bicycles a year.

“We just jumped in with both feet,” said Pashak, who started out as a bar owner in his native Calgary and wound up in Detroit, a city he had admired since childhood for its Motown music. “America needs jobs, which is a good reason to start making stuff here again.”

Detroit’s manufacturing startups have yet to have much impact on a city unemployment rate that stood at 11.7 percent in June. As a whole, they have created only a few hundred jobs, just a fraction of the 7,700 manufacturing jobs created in the sector from March 2012 to March 2013 in the Detroit metropolitan area, according government data.

Small as they are, Detroit’s manufacturing startups offer faint signs of economic diversification after decades of reliance on the automakers or grand schemes to revitalize Detroit such as casinos. They are also making relatively expensive niche goods in a city where consumer spending power has been battered for years.

“I think these small firms offer better hope for Detroit than any big answer,” said Margaret Dewar, an urban planning professor at the University of Michigan. “The city has always looked for a big solution to its problems, which hasn’t worked.”

The auto industry built Detroit, drawing hundreds of thousands of jobs here. But as U.S. automakers shifted production elsewhere, the city’s population fell from a peak of 1.8 million in 1950 to around 700,000, and only one large-volume auto plant still makes cars in the city. Detroit has long-term debt of more than $18 billion and on July 18 the state-appointed emergency manager, Kevyn Orr, filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy protection, the largest ever U.S. municipal bankruptcy.

Detroit’s new entrepreneurs have come despite the city’s strained finances, undaunted by the lack of street lights in many neighborhoods and patchy basic services like police and emergency services.

“Most of the people who have set up here are family and friends who have done so regardless of poor services,” said David Egner, executive director of the New Economy Initiative, a $100 million fund to aid entrepreneurs in Detroit.

They are encouraged by Orr’s plans to invest in services and infrastructure as part of the city’s restructuring. “Once services improve, I think we’ll see growth from companies outside that group of family and friends,” Egner said.

The largest of the city’s small newcomers is a watch maker called Shinola, a Depression-era brand name purchased in 2011 when the company set up shop. Dallas-based Bedrock Manufacturing, a venture capital firm backed by Tom Kartsotis, founder of accessory firm Fossil Inc., decided to take advantage of Detroit’s underutilized workforce and resonant Made-in-America mystique.

“When we came here we found a lot of dynamic young people who were not focused on Detroit’s past, but were looking to the future,” said Bedrock CEO Heath Carr. “There is a movement in the United States for Made in America goods, but our question was would they support it with their wallets, because most things made here are more expensive.”

Recent consumer research, including a November 2012 Boston Consulting Group survey, indicates around 80 percent of U.S. respondents are willing to pay a premium for American-made goods.

Bedrock spent an undisclosed sum on equipment and on months of training for workers to assemble Shinola watches in a clean environment not far from downtown Detroit. The parts mostly come from Switzerland or China, but the company has two certified watchmakers on staff who can modify designs.

“It means a lot to me to be able to make these watches here in Detroit,” said Jalil Kizy, a Detroit native and one of Shinola’s two watchmakers. Until Shinola came along, Kizy was like many Michigan natives who have felt they would need to leave the state to find work.

Shinola’s 75-person workforce has the capacity to produce 500,000 watches a year. The first batch of 2,500 watches, priced from $475 to $800 each, sold out in days early this year to buyers across the United States. The company has had teething problems delivering products, Carr said, in part because Shinola underestimated demand.

“It’s a good problem to have,” Carr said. “But we are working to manage customer expectations.”

Shinola also assembles Shinola bikes here, competing with at least two other small-scale bike makers: Detroit Bicycle Company and custom bike builder Slingshot Bikes, which is relocating from Grand Rapids in western Michigan. Pashak’s Detroit Bikes will employ 30 people when production begins in August.

“CRAZY OLD”

The city’s new manufacturers face challenges common to many new businesses: managing consumer expectations while struggling to meet demand, finding qualified workers to ramp up production, or bearing the cost of training new ones.

Eric Yelsma formed Detroit Denim after losing his job selling specialty printing chemicals once oil hit $100 a barrel in 2008. Yelsma wants to expand Detroit Denim’s four-person payroll, but few Americans know how to make jeans anymore.

“The labor pool for this business is pretty much minimal,” he said. “So far, we’ve come up dry.”

A local veterans’ group is considering a plan to fund a six-month training course for three veterans to become “jean smiths” on what Yelsma describes as “crazy old” sewing machines, one more than a century old. Detroit Denim’s jeans sell for $250.

Detroit Denim shares space with the non-profit Empowerment Plan, which makes sleeping bag coats for the homeless. Backed by Quicken Loans’ Gilbert and Spanx founder Sara Blakely, Empowerment Plan makes coats from donated materials – insulation from General Motors and material from workwear brand Carhartt.

Veronika Scott, a 24-year-old graduate of Detroit’s College for Creative Studies who founded Empowerment Plan, said most of the nine formerly homeless women she employs have found places to live since getting a job. Demand for the coats is strong enough that Scott is planning a “buy one, give one” program this fall: for $200, customers will get a coat and have one donated to a homeless person.

Andrew Pierce, U.S. president of marketing consultancy Prophet, said Detroit’s new manufacturers are tapping into Detroit’s reputation much as U.S. automake

r Chry

sler has with its “Imported from Detroit” commercials.

“The Detroit brand is very authentic and a little bit gritty in a good way,” Pierce said. Beyond a growing desire for American-made goods, the attraction of Detroit “is that part of the American dream is all about the rebuild out of a crisis.”

(Reporting By Nick Carey; Editing by David Greising and Claudia Parsons)

INQUIRIES

Media: PR Department

Partnership: Marketing

Information: Customer Service