December 2012

But many companies are stepping gingerly, avoiding sweeping claims and spelling out what “Made in the U.S.A.” means for their products. Consumers are more shrewd about how few consumer goods actually are made in the United States, leaving companies less wiggle room about the origin of products.

The Whirlpool Corporation, for example, specified in full-page print advertisements this year that 80 percent of its appliances “sold in the U.S. come from our U.S. factories.” Despite its deep American roots, the 101-year-old company — which makes Maytag, Amana, KitchenAid and Jenn-Air products — has, like other corporate giants, moved some manufacturing abroad.

As a result of its centennial celebrations last year, some consumers have urged the company to talk more about its American origins, said William Beck, a senior marketing director at Whirlpool, which spent $57.4 million in 2011 on advertising, according to Kantar Media, a WPP unit.

In recent months, the appliance giant has been underlining its American factories, and noting in its overall brand advertising that it employs about 22,000 workers (15,000 of them at its manufacturing plants), and spends $7.4 billion annually on operating and maintaining its factories in Iowa, Ohio, Oklahoma and Tennessee.

But Whirlpool, whose ad drew a full-page rebuttal from the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers accusing it of shutting factories in the United States, said nostalgia and similar sentiments do not drive its sales. “Whirlpool’s key differentiating points are quality and innovation,” said Mr. Beck, and “the icing is that, hey, we’re made in the United States.”

Whirlpool does not share its market research, but other market studies show that customers increasingly take note of where a product is made. Perception Research Services International, in a September study, found that four out of five shoppers notice a “Made in the U.S.A.” label on packaging, and 76 percent of them said they would be more likely to buy a product because of the label.

While shoppers, especially those over 35, say they want to help the economy by buying United States-made goods, “the motivating factors actually may be quality and safety,” said Jonathan Asher, executive vice president of Perception Research Services. The company, which is based in Teaneck, N.J., surveyed 1,400 consumers last summer. “People are paying attention in categories that are ingested like food, medicine and personal care products, but less so in electronics, office supplies and appliances,” he said.

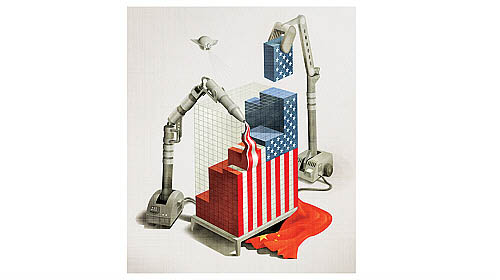

In a separate study, the Boston Consulting Group found that 80 percent of consumers surveyed said they would be willing to pay more for “Made in the U.S.A.” products than for those carrying a “Made in China” label.

They would pay the biggest differential for items like baby food and wooden toys, and a smaller percentage for electronics, apparel and appliances, said Kate Manfred, director of the group’s Center for Consumer and Customer Insight in the Americas, which released the study in mid-November.

“Safety and quality, and keeping jobs in America, are the important factors,” she said.

Bixbi, a Boulder, Colo., pet treat provider, has relied on safety to increase sales. The company, which started in 2008 amid revelations of tainted dog food ingredients imported from overseas, sells dog treats made from locally raised chickens and other animals.

“Our sales have grown 600 percent each year,” said James Crouch, who founded the small company with his brother, Michael. “Locally sourced is a key advantage.”

But for all the talk about American-made goods, Bixbi is one of the few clients that have adopted “Made in the U.S.A.” marketing, said Dave Schiff, co-founder of Made Movement, a Boulder advertising firm that handles the Bixbi account.

“Some customers think that the American-made label may just be window dressing and companies can be reluctant to use it,” Mr. Schiff said. He and two colleagues started their firm in April to enlist client companies that manufacture in the United States.

Classifying goods as American-made can be dicey, he discovered, because many products have parts that are made outside the United States. To generate interest in such products, as well as a revenue stream, his firm in July started a Made Collection Web site to sell American-made goods.

But finding goods manufactured in the United States for the Web site has been a challenge, Mr. Schiff said. Many items on the Web site are expensive, like a $225 dress shirt from Hamilton, the Houston company that makes Made in America apparel that competes with brands like Levi’s Vintage Clothing and Orvis, which also capitalize on manufacturing in the United States.

Companies are keenly aware that highlighting American-made credentials can backfire after the experience of the apparel maker Ralph Lauren. Renowned for its American nostalgia, Lauren provided uniforms for the 2012 United States Olympic team that were made in China. That resulted in threats of a boycott by some angry consumers.

Some companies like Exxel Outdoors, which makes camping, hunting and fishing equipment, have considered, then rejected, marketing their American-made credentials. Exxel makes two million sleeping bags annually at its Haleyville, Ala., factory.

“We do manufacture in the United States, but there are a lot of variables, like where the components are made. Some of ours come from abroad, so it could be confusing,” Harry Kazazian, the company’s chief executive, explained.

“Simply using the Made in the U.S.A. label is not enough,” said Jaynie L. Smith, chief executive of Smart Advantage, a consulting firm based in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

“Companies can be foreign owned,” said Ms. Smith, who wrote “Relevant Selling,” a book about corporate sales strategy. “But they need to say that ‘We are still on your soil. We create jobs. We make quality products, and we’re delivering them quickly.’ ”